Theodor Billroth, the master of German surgery, wrote in 1883: "A surgeon who attempts to operate on the heart will lose the respect of his peers”. Prophets are sometimes wrong ! In fact, the first operation in cardiac surgery was performed 65 years later, in 1948; it was a closed mitral commissurotomy. The history of cardiac anaesthesia is therefore a young one, barely 70 years old. The introduction of hypothermic extracorporeal circulation (1951), valve replacement (1961), coronary artery bypass grafting (1967) and transplantation (1967) have all led to developments in anaesthetic techniques. So it's important to start with a brief history of cardiac surgery as well as the heart-lung machine.

Cardiac surgery

In 1896, Ludwig de Rehn in Frankfurt treated a wound in the right ventricle with a direct suture for the first time. Heart surgery was born, 120 years ago. Rehn went on to perform the procedure 124 times, with a survival rate of 40% [7]. In 1907, Friedrich Trendelenburg of Leipzig described pulmonary embolectomy by occluding the pulmonary artery and extracting clots, but it was not until 1924, after many failures, that the first patient survived the operation.

The next stage, mainly in North America, began with closed-heart surgery procedures. These included ligation of the ductus arteriosus (Robert Gross, Boston 1938), systemic-pulmonary shunting as palliation to improve pulmonary flow in tetralogy of Fallot (Helen Taussig and Alfred Blalock, Philadelphia 1944) and mitral commissurotomy (Charles Bailey, Philadelphia 1948) [12].

The first "open heart" technique did not use extracorporeal circulation (ECC), but a 5 to 10 minute hypothermic arrest by cooling the surface of the heart (26°C) and occluding the inferior vena cava [18]. This allowed closure of atrial septal defects (ASD) and dilation of pulmonary or mitral stenoses [10]. With the exception of the Philadelphia case in 1953 (see below), none of the first 14 attempts at open-heart bypass surgery were successful [11]. It took a lot of perseverance to keep going ! From 1955, two teams, led by John Kirklin at the Mayo Clinic and Walton Lillehei at the University of Minnesota, were able to correct simple congenital malformations with success rates of 93% and 89% respectively [20].

The 1960s and 1970s saw the development of three key areas of cardiac surgery: valve replacement, coronary artery bypass grafting and transplantation. This decade also saw a number of other important developments: the compact disposable bubble oxygenator, the pacemaker (W. Chardack and W. Greatbatch in 1960, manufactured by Medtronic), and the intra-aortic balloon pump device (A. Kantrowitz in Brooklyn in 1967).

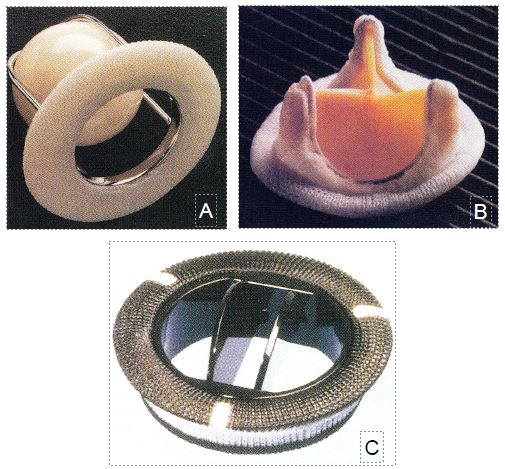

Albert Starr, a surgeon in Portland, Oregon, with the help of an engineer, Lowell Edwards, developed a prosthetic valve consisting of a ball held in a cage mounted on a ring (Figure 1.1A). It replaced the first mitral valve in 1961 and the first aortic valve in 1962. The Starr-Edwards valve has since been implanted in more than 175,000 patients [24]. At the same time, Donald Ross in London began to replace valves with aortic homografts and in 1967 described the operation that bears his name (autotransplantation of the pulmonary valve into the aortic position and replacement of pulmonary valve by heterograft) [16].

The second major event of this period was myocardial revascularisation surgery. As early as 1945, Vineberg in Montreal had taken the first steps in revascularisation surgery by implanting the internal mammary artery into the myocardium without anastomosis; the hypothetical development of collaterals was intended to revascularise the underlying muscle [23]. The real mammary artery graft was developed by Kolessov in Leningrad in 1964; lacking a ECC, he performed his anastomoses on beating hearts [8]. But the plenum of the Soviet Academy of Cardiology decided that "surgical treatment of coronary disease was impossible and had no future" [14]. That was the end of the Russian experiment. It was at the Cleveland Clinic in May 1967 that Effler and Favaloro introduced the technique of venous bypass between the aorta and the coronary arteries under ECC as it is performed today [5]. It has gradually become the most common cardiac surgical procedure, with approximately 1 million procedures performed each year.

Figure 1.1: Heart valve prostheses. A: Starr-Edwards cage-and-ball valve. B: Carpentier-Edwards biological valve. C: St.Jude mechanical double-fin valve.

Heart transplantation had a slow start. Described and developed on animals by Shumway in 1960, the technique was first used on humans on 3 December 1967 in Cape Town by Christian Barnard [1]; the patient died on the 18th day [7]. For a dozen years, only a few surgeons performed this unrewarding procedure, with 1-year survival rates ranging from 22% to 65% [9]: Shumway in Stanford, Barnard in Cape Town, Lower in Richmond and Cabrol in Paris [13]. The discovery in 1972 of the immunosuppressive effect of a fungal extract, cyclosporine A, on lymphocytes completely changed the outcome of heart transplantation, with 1-year survival rising to 83% and 3-year survival to 70% [15]. From then on, the operation became commonplace. Technical improvements, the codification of the concept of brain death and the introduction of new immunosuppressive drugs have made transplantation the treatment of choice for end-stage heart failure. To date, more than 70,000 orthotopic transplants have been performed. At present, the main limitation is the chronic shortage of donors.

The decade 1970-1980 saw new advances: the introduction of cold potassium cardioplegia (William Gay and Paul Ebert, 1973), the development of porcine biological valves (Alain Carpentier in Paris) and pyrocarbon mechanical valves (StJude Medical) (Figure 1.1 B and C), the arterial switch operation for transposition of great arteries (Jatene in Sao Paolo and Yacoub in London, 1975) and the marketing of the membrane oxygenator (Edwards Laboratory, 1975) [7]. Two innovations in related fields were to have a major impact on cardiac surgery: the Swan-Ganz pulmonary catheter (Henry Swan and William Ganz, Los Angeles 1970) and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (Andreas Grüntzig, Zurich 1977) [6,22]. Discoveries moved from the United States to the rest of the world.

In the following decade, mitral plasty was introduced by A. Carpentier in Paris and D. Cosgrove at the Cleveland Clinic [2], and the first coronary stents were placed by U. Sigwart in Lausanne [21]. Aprotinin was introduced in 1987 to reduce intraoperative bleeding [17]. John Kirklin's group in Alabama first drew attention to the importance of the systemic inflammatory syndrome induced by the extra corporeal circulation [4].

The last twenty years have been marked by technical refinements such as ultrafiltration, circuit miniaturisation, heparinised circuits and stentless valves. They have also been influenced by economic pressures and competition between centres, as if surgery were entering the age of commercialisation. The main aim of fast-track or beating heart techniques is to keep costs down. This is why beating heart coronary artery bypass surgery is widely used in emerging countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Turkey and India [3]. However, the last decade has seen the rise of percutaneous techniques and minimally invasive procedures such as transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) or percutaneous mitral valve repair (MitraClip™), as well as hybrid procedures performed in a dedicated room equipped with radiological and echocardiographic facilities to allow both surgery with ECC and percutaneous stent or valve placement.

What does the future hold for cardiac surgery? Since futurologists are always wrong because the unexpected overturns their extrapolations, it is wise to be content with predicting the short term. We can think of five main areas [19].

- Percutaneous catheterisation; TAVI and MitraClip have paved the way for more procedures performed by specialised multidisciplinary interventional teams of surgeons and cardiologists. With better bioprostheses, the technique will be extended to tricuspid and pulmonary valves and to a younger population. It will be complemented by hybrid procedures combining catheter and open heart surgery.

- Ventricular assist devices: The shortage of donors for transplantation and the increasing prevalence of heart failure will lead to an increase in the use of temporary or permanent haemodynamic assist devices. Even if their cost decreases, these techniques will remain the prerogative of privileged societies.

- Minimally invasive surgery: endoscopic and robotic techniques are already making it possible to perform limited access surgery, greatly improving post-operative recovery. The exceptional could become routine.

- Regenerative medicine: the combination of surgery and programmed stem cell delivery to reconstruct heart muscle or valve tissue could replace diseased parts with normal tissue, rather than using prostheses and leaving scars.

- Democratisation of surgery: just as some Indian clinics have opened their doors to the entire population, cardiac surgery in underprivileged countries needs to be developed to offer simple, fast and inexpensive operations to all social classes, with a high rate of rehabilitation without follow-up treatment.

| History of Cardiac Surgery |

| A few points of reference:

- 1944: Blalock-Taussig shunt - 1948: Closed mitral commissurotomy - 1953: First successful closure of ASD in ECC - 1961: MVR, 1962: AVR (Starr valve) - 1964: beating heart mammary bypass on IVA (Kolessov) - 1967: Coronary artery bypass graft, heart transplantation - 1977: PCI - 1987: Coronary stents - 2002: TAVI |

© PG Chassot April 2007, last update September 2019

Références

- BARNARD CW. A human cardiac transplant: An interim report of a successful operation performed at Groote-Schur Hospital, Capetown. S Afr Med J 1967; 41:1271-5

- CARPENTIER A. Cardiac valve surgery: the "French correction". J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1983; 86:323-8

- CHASSOT PG, Van der Linden P, Zaugg M, Mueller XM, Spahn DR. Off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: Physiology and anaesthetic management. Brit J Anaesth 2004; 92:400-13

- CHENOWETH DE, COOPER SW, HUGLI TE, et al. Complement activation during cardiopulmonary bypass. N Engl J Med 1981; 304:497-501

- FAVALORO RG. The present era of myocardial revascularization. Int J Cardiol 1983; 4:331

- GRUNTZIG AR, SENNING A, SIEGENTHALER WE. Nonoperative dilatation of coronary artery stenosis: percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. N Engl J Med 1979; 301:61-8

- HESSEL EA. History of cardiac surgery and anesthesia. In: ESTEFANOUS FG, BARASH PG, REVES JG. Cardiac anesthesia, prinsiples and clinical practice, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2001, 3-36

- KOLESSOV VI. Mammary artery-coronary artery anastomosis as method of treatment for angina pectoris. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1967; 54:535-44

- LANSMANN SL, ERGIN MA, GRIEPP RB. History of cardiac transplantation. In: WALLWORK J, ed. Heart and Heart-lung transplantation. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1989, 3-25

- LEWIS FJ, TAUFIC M. Closure of atrial septal defects with aid of hypothermia: experimental accomplishments and the report of one successful case. Surgery 1953; 33:52-60

- LILLEHEI CW. Historical development of cardiopulmonary bypass in Minnesota. In: GRAVLEE GP, DAVIS RF, KURUSZ M, eds. Cardiopulmonary bypass, principles and practice, 2nd edition. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2000, p 3-21

- LITWACK RS. The growth of cardiac surgery: historical notes. Cardiovascular Clinics 1971; 3:5

- LOWER RR, SHUMWAY NE. Studies on orthotopic transplantation of the canine heart. Surgical Forum 1960; 11:18

- MUELLER RL, ROSENGART TK, ISOM DW. The history of surgery for ischemic heart disease. Ann Thorac Surg 1997; 63:869-78

- ROBBINS RC, BARLOW CW, OYER PE, et al. Thirty years of cardiac transplantation at Stanford University. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999; 117:939-44

- ROSS DN. Replacement of aortic and mitral valve with a pulmonary autograft. Lancet 1967; 2:956-60

- ROYSTON D, BIDSTRUP BD, TAYLOR KM, et al. Effect of aprotinin on need for blood transfusion after repeat open-heart surgery. Lancet 1987; 2;1289-92

- SELLICK BA. A method of hypothermia for open heart surgery. Lancet 1957; 1:443-7

- SHEMIN RJ. The future of cardiovascular surgery. Circulation 2016; 133:2712-5

- SHUMACKER HB. The evolution of cardiac surgery. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 1992

- SIGWART U, PUEL J, MIRKOVITCH V, et al. Intravascular stents to prevent occlusion and restenosis after transluminal angioplasty. N Engl J Med 1987; 316:701-6

- SWAN HJC, GANZ W, FORRESTER J, et al. Catheterization of the heart with use of a flow-directed balloon-tipped catheter. N Engl J Med 1970; 283:447-52

- VINEBERG A. Development of anastomosis between coronary vessels and transplanted internal mammary artery. Can Med Ass J 1946; 55:117

- WESTABY S, BOSHER C. Landmarks in cardiac surgery. Oxford: Isis Medical media, 1997