Generally, management of surgery or bleeding on anticoagulants depends on a combination of risks.

- Low bleeding risk, high thrombotic risk: local measures (compression, surgical or endoscopic haemostasis), maintenance of anticoagulation;

- High bleeding risk, low thrombotic risk: discontinue anticoagulants, antagonise in case of life threat;

- High bleeding and thrombotic risk: minimal interruption of anticoagulants, careful antagonism, case-by-case solution.

- Degree of urgency: life-threatening injuries or highly bleeding emergency procedures require immediate reversal of anticoagulation. When the procedure can wait 1-2 days, simple interruption of treatment is enough due to the relatively short half-life of new oral anticoagulants (4-16 hours); this does not apply to anti-vitamin K agents (AVK) whose duration of action exceeds 4-5 days.

In complex cases, always consult an haematologist.

Pre-operative times

In simple terms, the serum level of a drug drops to 12.5% of its initial value after 3 half-lives and to 3% after 5 half-lives. The elimination half-life of the substances (see Table 8.2 ) therefore determines time between discontinuation of treatment and surgical procedure. While there are recommendations for time limits for treatment with heparins and anti-vitamin K drugs, there are insufficient data on the newer oral anticoagulants (NOACs) to enact evidence-based rules for pre-operative management. For the time being, we rely on proposals made by expert groups based on the pharmacokinetics of these substances [6,16,19,20,26,32]. The minimum preoperative withdrawal times usually proposed are as follows (standard bleeding risk, normal liver and kidney function) (see Table 8.12).

- Non-fractionated heparin 4-6 h

- LMWH prophylaxis 12 h (24 h if creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min)

- LMWH therapy 24 h (48 h if creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min)

- Fondaparinux (Arixtra® ) 48 h (4-6 days if creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min)

- Dabigatran (Pradaxa® ) 48 h (3-5 days if creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min)

- Apixaban (Eliquis® ) 48 h (3-4 days if creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min)

- Edoxaban (Savaysa® , Lixiana® ) 48 h (3-5 days if creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min)

- Rivaroxaban (Xarelto® ) 5-10 mg 24 h (2-3 days if creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min) 15-20 mg 48 h (3-4 days if creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min)

- Sintrom® , Coumadin® 5 days (INR check at D-5 and D-1)

- Marcoumar ® 10 days (INR check at D-10 and D-1)

- Desirudine (Iprivask® ) 10 h

- Bivalirudin (Angiox® ) 4-10 h

- Danaparoid (Orgaran® ) 48 h

- Argatroban (Argatroban Inj® ) 4 h

Taking into account a delay of 3 half-lives and high values for the plasma half-life of each substance, it can therefore be recommended, simply, to wait 48 hours before a low-risk bleeding operation for all NOACs, except for rivaroxaban at 5-10 mg/d in simple operations in patients without comorbidity, where this delay can be reduced to 24 hours. However, a delay of 5 half-lives is recommended for surgery at high risk of bleeding, for spinal LRA or deep blocks (including periclavicular blocks), in elderly patients and in patients taking substances that delay the elimination of NOACs such as amiodarone [1,6,15,19,23,26,30]. Indeed, after 48 hours, about 15% of patients still show significant anticoagulant activity [10]. In case of renal failure, these times are doubled for substances with high renal elimination (LMWH and dabigatran 80%, edoxaban 45%), or increased by at least 24 hours for others (rivaroxaban 35%, apixaban 25%). Given the lack of clinical experience with the new oral anticoagulants and their lack of available antagonists (except for dabigatran), it is necessary to remain extremely cautious with the indications for spinal ALR in patients receiving one of these drugs [1]. Minor procedures without bleeding risk (dentistry, ophthalmology, wall surgery, etc) can be performed without interruption of NOACs, although care should be taken to operate when serum levels are low (between 8 and 18 hours after the last dose) [3,20].

Residual concentrations

The residual level of dabigatran and rivaroxaban is about 30-50 ng/mL after 4 half-lives; in the RE-LY (dabigatran) and ROCKET-AF (rivaroxaban) studies, this level allowed patients to undergo surgery without an increased bleeding risk [29]. With the specific anti-Xa tests for each of the new agents, it is possible to obtain a serum concentration of the substance and to have a good estimate of the bleeding risk as well as of the waiting time (provided that the renal function is normal) [12,299]. The following values are consensus in the current literature.

- Residual level < 30 ng/mL: minimal bleeding risk (suitable for major surgery)

- Residual level 30-50 ng/mL: acceptable risk for low bleeding surgery;

- Level 50-200 ng/mL : wait 12-24 hours;

- Level 200-400 ng/mL : wait > 24 hours (usually 48 hours);

- Levels > 400 ng/mL :

The test is repeated every 12 to 24 hours until the level falls below the safe level of 30-50 ng/mL, a value that is currently quite arbitrary. These recommendations are for patients with normal renal function, undergoing procedures without excessive bleeding risk.

So far, there is only one study that justifies preoperative delays by residual plasma NOAC levels (422 patients, 60% of whom are major surgery cases) [14]. Its results can be summarised as follows.

- An interruption of 25-48 hours leaves 38% of patients with a concentration > 30 ng/mL and 7% with > 100 ng/mL;

- With an interruption of 49-72 hours, 95% of patients have a level < 30 ng/mL and none have a level > 50 ng/mL;

- Predictors of a residual concentration >30 ng/mL are: too short a time, creatinine clearance <50 mL/min, antiarrhythmic therapy (amiodarone, verapamil), and heparin substitution;

- An anti-Xa activity ≤ 0.1 IU/mL for xabans and a normal TT for dabigatran exclude residual anticoagulant levels, while PT and aPTT have no significant predictive value.

48 hours for a simple operation and 72 hours for a risky operation are therefore justified by these results. However,take into account that

- Serum NOAC levels are extremely variable between individuals for the same assays and for the same waiting times: between 0 and 48 hours, these levels vary from < 30 ng/mL to > 200 ng/mL [14].

- There is no clear correlation between serum levels and bleeding risk, probably because the latter is too multifactorial. However, substances that interfere with the metabolism of NOACs and extend their anticoagulant activity (amiodarone, phenytoin, fluconazole, rifampicin) significantly increase the risk of spontaneous bleeding [5,23].

Detailed perioperative management

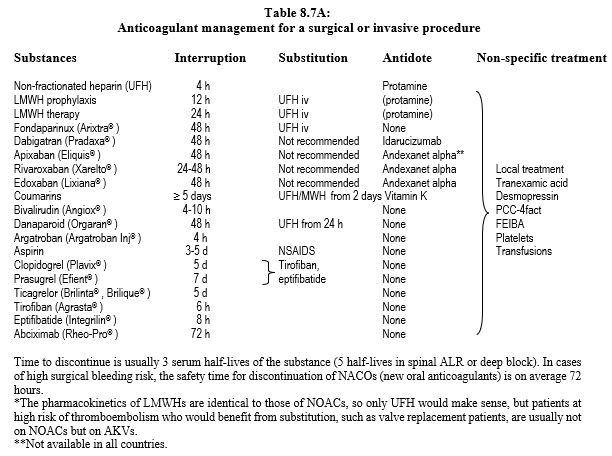

Preoperative anticoagulant management can be summarised as follows (Table 8.7A, see also Tables 8.11 and 8.12) [1,6,8,9, 11,13,16,19,24,26,29,30,33,34].

- Non-fractionated heparin (UFH); interrupt infusion 4-6 hours preoperatively. In cardiac surgery for acute coronary syndrome or valve thrombosis: continue infusion until induction. Same for bivalirudin.

- Control: aPTT, ACT.

- Specific antidote: protamine.

- Low molecular weight heparins (LMWH); duration of interruption depends on the subcutaneous dose.

- Prophylactic LMWH (10,000-12,000 IU/24 h): 12 hour interruption.

- LMWH therapy (≥ 20,000 IU/24 h): 24-hour interruption; possible substitution with intravenous UFH for 12-20 hours.

- Control of residual effect: anti-Xa effect.

- Partial antidote: protamine.

- Doubled in case of renal failure.

- Fondaparinux (Arixtra® ): 48 to 72 hours interruption depending on surgery bleeding risk .

- Extended to 4-6 days if creatinine clearance is < 50 mL/min.

- Control of residual effect: anti-Xa effect.

- Substitution with intravenous UFH reserved for cases with very high thrombo-embolic risk and prolonged delay.

- No specific antidote.

- Anti-vitamin K (AVK); preoperative discontinuation of 5 days (warfarin, acenocoumarol) to 10 days (phenprocoumone). An INR value of < 2.0 is usually sufficient to perform surgery with moderate bleeding risk, whereas an INR < 1.5 is required for major surgery. Check INR 24 hours before surgery. Discontinuation of AVKs is not necessary before dermatological surgery, dentistry, ophthalmology (cataract), endoscopy or pacemaker insertion (decision algorithm: see Figure 8.15) [7].

-

- Substitution only if high thromboembolic risk (heart valve prosthesis, history of stroke, target INR ≥ 3.0): UFH or LMWH as early as 48-72 hours after the last dose (see below). In other cases (target INR < 3.0), substitution is no longer recommended.

- Specific antidote: vitamin K (Konakion® ) 2.5-5 mg iv/12 h in case of emergency; target effect after 12 hours. If elective operation and INR 1.5 - 2.0: 1-2 mg vitamin K per os.

- Non-specific antidote (indicated for intracranial haemorrhage or massive haemorrhage): 4-factor prothrombin complex (PCC prothrombin complex concentrate); it is much more effective than FFP and does not bring a volume overload risk [21].

- Dabigatran (Pradaxa® ); adjusting time of preoperative discontinuation according to creatinine clearance and bleeding risk of the procedure. The surgical bleeding risk is the same when dabigatran is stopped 48 hours before surgery as when warfarin is stopped for 5 days [18]. In surgery without interruption of anticoagulant, the bleeding risk is 4 times lower with dabigatran than with warfarin [4].

- Preoperative withdrawal time: 48 or 72 hours depending on the surgery bleeding risk (creatinine clearance > 50 mL/min), 3-5 days if creatinine clearance < 50 mL/min).

- Residual effect control: diluted thrombin time (dTT, Hemoclot™), ecarin time; TT: sensitive but not quantitative.

- Antidote: idarucizumab (Praxbind® ) (see Antagonism).

- Rivaroxaban (Xarelto® ), apixaban (Eliquis® ), edoxaban (Lixiana® ); 48 hours off treatment is usually sufficient, given their short half-life.

- Extended to 72 hours in case of high risk bleeding operation or spinal LRA.

- An additional 24-hour delay if creatinine clearance is < 50 mL/min or if the patient is on amiodarone (Cordarone® ) [23].

- Reduced time to 24 hours for rivaroxaban 10 mg/d for a simple operation in a patient without comorbidity.

- 24 hour delay for rivaroxaban 2x 2.5 mg/d.

- Residual effect control: anti-Xa activity. Prolonged PT: persistence of effect (non-quantitative). TT, TPT, fibrinogen, factor XIII and D-dimer are not influenced [2].

- No specific antidote at present (in preparation); 4-factor prothrombin complexes are probably effective (see Antagonism).

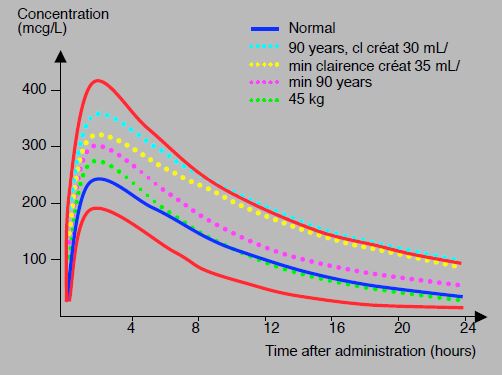

High inter-individual variability and the effect of age or renal impairment lead to variations of 1 to 4 in the residual rivaroxaban level 12 to 24 hours after the last dose; the level of 50 ng/mL, considered the cut-off value for surgery, is reached in 12 to 48 hours depending on the patient; the safety threshold for bleeding surgery is 30 ng/mL [27]. This high variability requires great caution in cases of high bleeding risk or in loco-regional spinal anaesthesia (see Figure 8.11A).

Figure 8.11 A: Rivaroxaban (20 mg 1 x/d) concentration-time profiles in different situations: 90-year-old patients with renal failure (turquoise dotted line), patients with creatinine clearance of 35 mL/kg (yellow dotted line), 90-year-old patients (purple dotted line), 45 kg patients (green dotted line). standard curve individual is shown in blue. In red, 5th and 95th percentile curves; the upper value is approximately 3 times the lower value [modified from ref 27].

In patients at-risk or in emergencies, the duration of the preoperative interruption can be decided on the basis of the plasma level (as measured by the anti-Xa effect). Since the clinical effect is proportional to this level, there is no need for substitution when waiting period is extended due to renal failure, since the patient is sufficiently anticoagulated by the residual effect.

Based on their half-life, a basic recommendation to discontinue new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) preoperatively is [25,29,32,35,36].

- Urgent operation: wait at least 1 half-life;

- Surgery with no or low risk of bleeding: no interruption, but better operate 8-10 hours after the last dose;

- Surgery with low or moderate bleeding risk: wait 3 half-lives (48 hours);

- High-risk bleeding operation: wait 5 half-lives (72 hours);

- Loco-regional spinal anaesthesia (LRA), deep blocks (including periclavicular blocks): wait 5 half-lives;

- Surgery in case of renal failure: wait > 5 half-lives (3-5 days);

- Pending the availability of antidotes for all NOACs, a rather conservative and cautious attitude is required; spinal ALR and deep blocks are not recommended [1];

- Substitution with heparin is not necessary.

As the new anticoagulants have a high renal excretion component (all for fondaparinux and dabigatran, half for edoxaban, one third for rivaroxaban and one quarter for apixaban), preoperative discontinuation times are extended accordingly in cases of moderate (creatinine clearance 30-50 mL/min) or major (creatinine clearance 15-30 mL/min) renal impairment.

- Fondaparinux: 4-6 days (depending on bleeding risk);

- Dabigatran: 3-5 days (same);

- Xabans: 3-5 days (idem).

NOACs are contraindicated when creatinine clearance is <15 mL/min (dabigatran <30 mL/min).

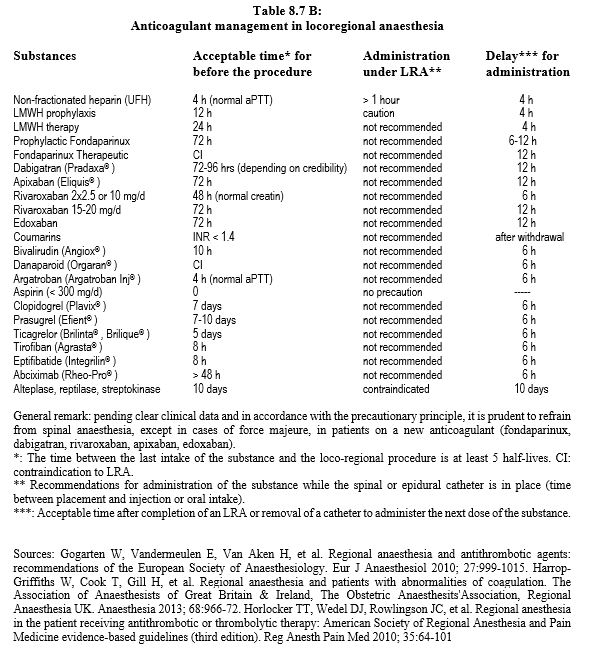

Loco-regional anaesthesia

Spinal anaesthesia (LRA) should only be considered when there is a high probability that the anticoagulant effect of the substance has completely disappeared, i.e. after5 half-lives of elimination [25,28]. Epidurals, spinal anaesthesia and deep or periclavicular blocks should be performed with extreme caution in patients receiving NOACs due to the lack of clear clinical data and the possibility of a less risky alternative (general anaesthesia) [33,35]. Pending better evidence and in line with the precautionary principle, it is prudent to limit spinal anaesthesia to cases of force majeure in patients on a new anticoagulant (fondaparinux, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban) [1]. These recommendations are intentionally conservative for three reasons: 1) spinal LRA is not a therapeutic procedure, 2) it brings intrinsic risks, and 3) safer alternatives exist [25,28]. The recommended times should be adapted to the specific bleeding risk of the surgery and to the renal function for renally eliminated substances. The recommended time between the last dose of anticoagulant and the removal of the epidural catheter is the same as the time between the last dose and the spinal puncture. It is recommended to wait 12 hours after puncture or after removal of the epidural catheter before starting treatment with an anti-thrombin or anti-Xa drug [1,15,30,33,37]. In case of haemorrhagic puncture, this delay is extended to 24 hours [10].after thrombolysis, locoregional therapy is not allowed for 10 days. These data are summarised in Table 8.7B [15,17,22]. Data are based on atraumatic punctures; it is clear that spinal haematoma risk is directly related to the number of attempts. For operations under anticoagulant therapy such as cardiac surgery, a bleeding puncture requires a 24-hour postponement of the procedure.

Postoperative

Postoperative resumption of anticoagulation is imperative because the risk of thrombosis is increased after the operation, but is conditioned by quality of haemostasis and by possible consequences of haemorrhage (bleeding in a closed space). Heparin or LMWH is restarted 12-48 hours after the end of the procedure, usually with a prophylactic dose; the therapeutic dose is reached on 2nd day , except in cases of mechanical prosthesis, rheumatic mitral stenosis or anamnesis of embolic stroke which must be permanently protected by a fully effective anticoagulation. Time to restart heparin depends on bleeding risk, quality of haemostasis and degree of thrombo-embolic threat [8,9]. AVKs can be restarted within the first 24 hours, as their effect will only be effective after 3 days. NOACs, on the other hand, are effective 1-3 hours after ingestion. With the former, it is advisable to use LMWH at a prophylactic dose for 72 hours in patients at high thrombo-embolic risk. With the latter, substitution is unnecessary or even dangerous; resumption time is 12-72 hours: on average 24 hours if risk of bleeding is low and 48-72 hours if it is high [1,6,33]. It is possible to start with a lower dose for a few days if situation is worrying. When haemostasis is difficult, wait 2-3 days before restarting, but when the risk of thromboembolism is high, it is important to restart as soon as possible, i.e. the day after the operation, or temporarily substitute a heparin [31,35].

However, stopping NOACs for 48-72 hours before a bleeding operation and restarting them 48-72 hours afterwards leaves a gap of 4-6 days without treatment, which is dangerous in a patient at high thrombo-embolic risk. In this case, it is probably appropriate to substitute anticoagulation with heparin to protect the patient [1]. Despite its intravenous administration, non-fractionated heparin has the advantage of a short half-life (1-2 hours) and the availability of an antagonist (protamine).

After major procedures, it should be taken into account that renal function may be impaired for many days and the dose of NOAC should be adjusted accordingly. As long as the oral route is excluded, a replacement LMWH is recommended; as the pharmacokinetics of LMWH and NOACs are similar, there should be no overlap between the two therapies. Since NOACs are only available in oral form, they are crushed and administered through a stomach tube if feeding is not possible. However, this is not possible for dabigatran, whose capsules must not be opened; in these circumstances, substitution with LMWH should be considered [26].

| Perioperative management of anticoagulants |

|

In general, pre-operative withdrawal times are based on the half-life of substance and are doubled in renal failure for substances eliminated by the kidneys.

- Urgent operation: wait at least 1 half-life

- Surgery with moderate bleeding risk: wait 3 half-lives

- High bleeding risk surgery, spinal ALR: wait 5 half-lives

Substitution with UFH is considered in cases of high thrombo-embolic risk if the interruption lasts > 48 hours.

Recommended timeframe :

- Non-fractionated heparin 4 h

- LMWH (prophylactic) 12 h

- LMWH (therapeutic) 24 h (48 h if creatinine < 50 mL/min)

- Fondaparinux 48 h (4-6 days if creatinine < 50 mL/min)

- Dabigatran 48 h (3-5 days if creator Cl < 50 mL/min)

- Apixaban 48 h (3-4 days if creator Cl < 50 mL/min)

- Edoxaban 48 h (3-5 days if creator Cl < 50 mL/min)

- Rivaroxaban 5-10 mg 24 h (3 days if creatinine < 50 mL/min)

- Rivaroxaban 15-20 mg48 h (3-4 days if creatinine < 50 mL/min)

- Sintrom® , Coumadin® 5 days (INR check at D-5 and D-1)

- Marcoumar® 10 days (INR check at D-10 and D-1)

Taking into account a delay of 3 half-lives and the high values for the plasma half-life of each substance, it can be recommended, simply, to wait 48 hours for all NOACs, except for rivaroxaban 10 mg/d in simple procedures in patients without comorbidity where this delay can be reduced to 24 hours. For situations with a high risk of bleeding and for spinal LRA, it is recommended to extend this period to 72 hours. Time for removal of catheter is the same as that for insertion. In case of renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance 15-50 mL/min) extend the preoperative delay from 72 to 120 hours, depending on bleeding risk and degree of renal elimination of the substances (dabigatran 80%, edoxaban 50%, rivaroxaban 33%, apixaban 25%). The time for resumption of anticoagulation depends on bleeding risk, the quality of haemostasis and the degree of thrombo-embolic threat, but is generally 12-48 hours. In complex cases, it is always prudent to consult an haematologist.

|

© CHASSOT PG, MARCUCCI Carlo, last update November 2019.

References

- ALBALADEJO P, BONHOMME F, BLAIS N, et al. Management of direct oral anticoagulants in patients undergoing elective surgeries and invasive procedures: update guidelines from the French Working Group on Perioperative Hemostasis. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2017; 36:73-6

- BARRETT YC, WANG Z, et al. Clinical laboratory measurement of direct factor Xa inhibitors: anti-Xa assay is preferable to prothrombin time assay. Thromb Haemost 2010; 104:1263-71

- BONHOMME F, HAFEZI F, BOEHLEN F, HABRE W. Management of antithrombotic therapies in patients scheduled for eye surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2013; 30:449-54

- CALKINS H, WILLEMS S, GERSTENFELD EP, et al. Uninterrupted Dabigatran versus Warfarin for ablation in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:1627-36

- CHANG SH, CHOU IJ, YEH YH, et al. Association between use of non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants with and without concurrent medications and risk of major bleeding in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. JAMA 2017; 318:1250-9

- DOHERTY JU, GLUCKMAN TJ, HUCKER WJ, et al. 2017 ACC Expert consensus decision pathway for periprocedural management of anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69:871-98

- DOUKETI JD. Perioperative management of patients who are receiving warfarin therapy: an evidence-based and practical approach. Blood 2011; 117:5044-9

- DOUKETIS JD, BERGER PB, DUNN AS, et al. The perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th edition). Chest 2008; 133:299S-339S

- DOUKETI JD, SPYROPOULOS AC, SPENCER FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines, Chest 2012; 141 (2 suppl): e326S-50S

- DUBOIS V, DINCQ AS, DOUXFILS J, et al. Perioperative management of patients on direct oral anticoagulants. Thromb J 2017; 15:14

- EHRA - European Heart Rhythm Association. EHRA practical guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonists and oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. www.escardio.org/EHRA, 2018

- FARAONI D, LEVY JH, ALBALADEJO P, et al. Updates in the perioperative and emergency management of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. Critic Care 2015; 19:203

- GAVILLET M, ANGELILLO-SCHERRER A. Quantification of the anticoagulatory effect of novel anticoagulants and management of emergencies. Cardiovasc Med 2012; 15:170-9

- GODIER A, DINCQ AS, MARTIN AC, et al. Predictors of pre-procedural concentrations of direct oral anticoagulants: a propsective multicentre study. Eur Heart J 2017; 38:2431-9

- GOGARTEN W, VANDERMEULEN E, VAN AKEN H, et al. Regional anaesthesia and antithrombotic agents: recommendations of the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2010; 27:999-1015

- GSLA/ AGLA. Lipid and Atherosclerosis Working Group, Swiss Society of Cardiology. 2017 Antithrombotics. Practical overview of the use of antithrombotics in cardiovascular disease. www.gsla.ch

- HARROP-GRIFFITHS W, COOK T, GILL H, et al. Regional anaesthesia and patients with abnormalities of coagulation. The Association of Anaesthesists of Great Britain & Ireland, The Obstetric Anaesthesits'Association, Regional Anaesthesia UK. Anaesthesia 2013; 68:966-72

- HEALEY JS, EIKELBOOM J, DOUKETIS J, et al. Periprocedural bleeding and thromboemblic events with dabigatran compared with warfarin. Circulation 2012; 126: 343-8

- HEIDBUCHEL H, VERHAMME P, ALINGS M, et al. European Heart Rythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Europace 2015; 17:1467-507

- HEIDBUCHEL H, VERHAMME P, ALINGS M, et al. Updated European Heart Rythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Executive summary. Eur Heart J 2017; 38:2137-49

- HICKEY M, GATIEN M, TALJAARD M, et al. Outcomes of urgent warfarin reversal with frozen plasma versus prothrombin complex concentrate in the emergency department. Circulation 2013; 128:360-4

- HORLOCKER TT, WEDEL DJ, ROWLINGSON JC, et al. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine evidence-based guidelines (third edition). Reg Anesth Pain Med 2010; 35:64-101

- KASERER A, SCHEDLER A, JETTER A, et al. Risk factors for higher-than-expected residual rivaroxaban plasma concentrations in real-life patients. Thromb Haemost 2018; 118:808-17

- KOVAKS RJ, FLAKER GC, SAXONHOUSE SJ, et al. Practical management of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65:1340-60

- LEITCH J, VAN VLYMEN J. Managing the perioperative patient on direct oral anticoagulants. Can J Anesth 2017; 64:656-72

- MAR PL, FAMILTSEV D, EZEBOWITZ MD, et al. Periprocedural management of anticoagulation in patients taking novel oral anticoagulants: Review of the literature and recommendations for specific populations and procedures. Int J Cardiol 2016; 202:578-85

- MUECK W, LENSING AWA, AGNELLI G, et al. Rivaroxaban. Population pharmacokinetic analyses in patients treated for acute deep-vein thrombosis and exposure simulations in patients with atrial fibrillation treated for stroke prevention. Clin Pharmacokinet 2011; 50:675-86

- NAROUZE S, BENZON HT, PROVENZANO DA, et al. Interventional spine and pain procedures in patients on antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. Guidelines from the ASRA, ESRA, AAPM, INS, NANS and WIP. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2015; 40:182-212

- PERNOD G, ALBALADEJO P, GODIER A, et al. Management of major bleeding complications and emergency surgery in patients on long-term treatment with direct oral anticoagulants, thrombin or factor Xa inhibitors: proposals of the Working Group on Perioperative Haemostasis (GIHP) - March 2013. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2013; 106:382-93

- RAVAL AN, CIGARROA JE, CHUNG MK, et al. Management of patients on non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in the acute care and periprocedural setting. Circulation 2017; 135:e604-e633

- SAMAMA MM, CONTANT G, SPIRO TE, et al. Laboratory assessment of rivaroxaban: a review. Thrombosis Journal 2013; 11:11

- SIÉ P, SAMAMA CM, GODIER A, et al. Surgeries and invasive procedures in patients treated long-term with an oral anti-IIa or anti-Xa direct anticoagulant. Proposals from the Perioperative Haemostasis Interest Group (GIHP) and the Haemostasis and Thrombosis Study Group (GEHT). Ann Fr Anesth Réanim 2011; 30: 645-50

- SPAHN DR, BEER JH, BORGEAT A, CHASSOT PG, et al. New oral anticoagulants in anesthesiology. Transf Med Hemother 2019; 46:282-93

- SPAHN DR, BORGEAT A, KERN C, CHASSOT PG, et al. Treatment with rivaroxaban. Recommendations of the SSAR expert group. www.sgar-ssar.ch, 2019

- TURPIE AG, KREUTZ R, LLAU J, et al. Management consensus guidance for the use of rivaroxaban - an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. Thromb Haemost 2012; 108:876-86

- WEITZ JI, QUINLAN DJ, EIKELBOOM JW. Periprocedural management and approach to bleeding in patients taking dabigatran. Circulation 2012; 126:2428-32

- WYSOKINSKI WE, McBANE RD. Periprocedural bridging management of anticoagulation. Circulation 2012; 126:486-90