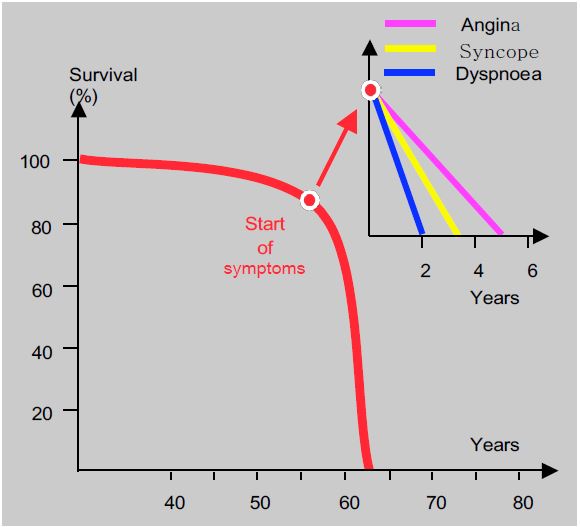

Clinical symptoms occur when preload reserve is exhausted, but not because contractile function has failed. This is in contrast to volume overload, such as mitral or aortic regurgitation, where ventricular failure may occur before clinical symptoms. Curiously, the severity of symptoms is not directly related to the severity of the stenosis, as it is not uncommon to find patients in good condition despite a transvalvular gradient of 150 mmHg. However, the size of the gradient does have prognostic value: the rate of cardiac events within 2 years is 16% when the maximum gradient is less than 40 mmHg and 79% when it is greater than 64 mmHg [8]. The disease can remain asymptomatic for a long time, with half of patients with a narrow stenosis (S ≤ 0.6 cm2 /m2 ) having no symptoms at all [6]. The rate of progression of the disease is unpredictable; however, the annual survival rate of patients treated conservatively is 92%, and two-thirds of them become symptomatic within 5 years [9]. The onset of symptoms significantly alters the prognosis: life expectancy is only 5 years after the onset of angina, 3 years after the onset of syncope and less than 2 years after the onset of dyspnoea (Figure 11.110) [4]. The incidence of sudden death is low in asymptomatic patients (1-1.5%/year), but becomes significant when symptoms occur: 3% of patients die within 3-6 months [6], probably following ventricular arrhythmias.

The prognosis of aortic stenosis is generally based on the degree of stenosis and the severity of symptoms. However, the effect of excess afterload on the performance of the LV and other cardiac structures is also an important factor. LV dysfunction, LA dilatation, mitral regurgitation, pulmonary hypertension and right-sided decompensation reflect the progressive impact of the lesion on upstream structures, as evidenced by a parallel increase in 1-year mortality from 4% to 24% [5].

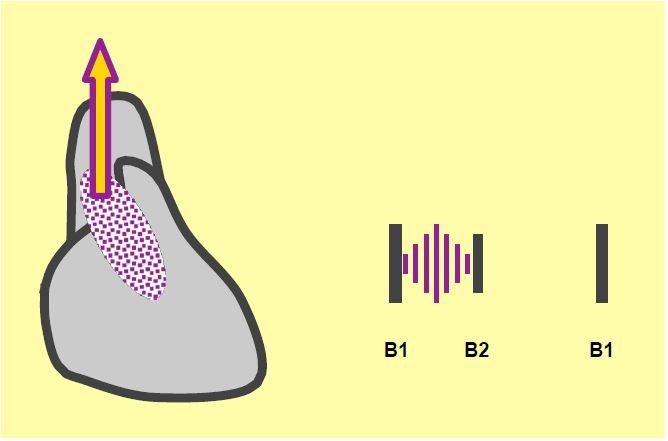

Auscultation is typical: a raspy crescendo-decrescendo ejection murmur with systolic thrill, maximum in the second right intercostal space, radiating towards the neck vessels, and attenuation or disappearance of B2, which is specific to the immobility of the aortic valve (Figure 11.111) [1]. However, this murmur is not proportional to the degree of stenosis, but to the intensity of the turbulence generated at the aortic valve outlet; these vortices are a function of the pressure gradient, the vibrational capacity of the aortic cusps and the resonance of the aortic root. As ventricular function deteriorates, the murmur becomes less intense. Even if the stenosis is only moderate, a well-functioning ventricle and a sclerotic aorta will produce a murmur of maximum intensity [1]. The arterial curve is not very wide and the systolic rise is slow (pulsus parvus and tardus); it resembles a damped curve or that of left ventricular failure (see Figure 11.147).

The ECG is dominated by signs of left ventricular hypertrophy: high voltage, left orientation of the QRS axis, Sokolow index > 3.5 mV, prolonged depolarisation, progressive shift of the ST segment and T wave in the opposite direction to the QRS; left bundle-branch block may be associated. A morphology similar to that of ischaemia may occur in the form of ST segment abnormalities and T inversion at V5-V6 (strain pattern), making differential diagnosis difficult.

Figure 11.110: In aortic stenosis, the onset of symptoms significantly alters the prognosis: life expectancy is only 5 years after the onset of angina, 3 years after the onset of syncope and less than 2 years after the onset of dyspnoea [4].

Figure 11.111: Auscultation in aortic stenosis. Rough ejection murmur radiating to the cervical vessels, diminished or absent B2 (specific for aortic valve immobility).

The chest radiograph shows a heart that is usually of normal size but with a rounded apex. Poststenotic dilatation of the aorta, more pronounced in bicuspid aortic valve disease, unrolls the right edge of the aortic silhouette. Calcification of the valve is sometimes seen.

| Clinical picture of aortic stenosis |

| Long latency before symptoms appear, but their appearance reduces survival to 5 years for angina, 3 years for syncope and < 2 years for dyspnoea. Symptoms often precede LV dysfunction. Dysfunction criterion: LV end-diastolic diameter > 4 cm/m2.

Auscultation: coarse ejection murmur with systolic thrill, single B2. Features of aortic stenosis Concentric LVH, preserved systolic function |

References

- BRAUNWALD E. Valvular heart disease. In: BRAUNWALD E. ed. Heart disease. Philadelphia, WB Saunders Co, 1997, 1007-76

- CARABELLO BA. Aortic stenosis. Cardiol Rev 1993; 1:59-68

- CASONATO A, SPONGA S, PONTARA E, et al. Von Willebrand factor abnormalities in aortic valve stenosis : pathophysiology and impact on bleeding. Thromb Haemost 2011 ; 106 :58-66

- FRANK S., JOHNSON A., ROSS J. - Natural history of valvular aortic stenosis. Br. Heart J 1973; 35:41-8

- GÉNÉREUX P, PIBAROT P, REDFORS B, et al. Staging classification of aortic stenosis based on the extent of cardiac damage. Eur Heart J 2017; 38:3351-8

- GÉNÉREUX P, STONE GW, O'GARA PT, et al. Natural history, diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic strategies for patients with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67:2263-88

- GREEN SJ, PIZZARELLO RA, PADMANABHAN VT, et al. Relation of angina pectoris to coronary artery disease in aortic valve stenosis. Am J Cardiol 1985; 55:1063-8

- OTTO CM, BURWASH IG, LEGGET ME, et al. Prospective study of asymptomatic valvular aortic stenosis: Clinical, echocardiographic and exercise predictors of outcome. Circulation 1997; 95:2262-70

- TANIGUSHI K, MORIMOTO T, SHIOMI H, et al. Initial surgical versus conservative strategies in patients with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66:2827-38

- VINCENTELLI A, SUSEN S, LE TOURNEAU T, et al. Acquired von Willebrand syndrome in aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:343-9