Risk of thrombosis

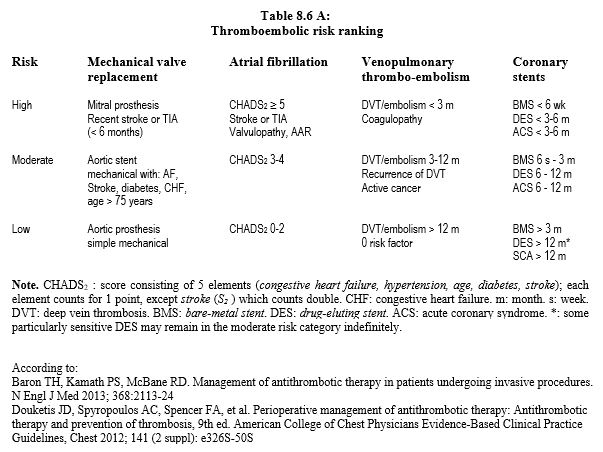

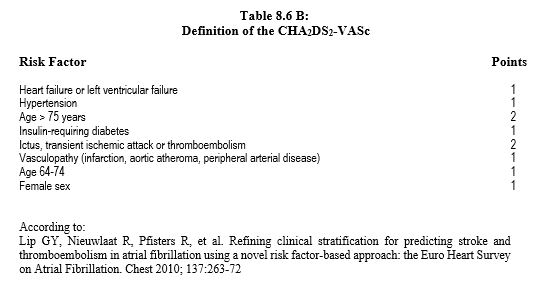

Thromboembolic risk is classified into 3 categories: low, moderate and high. It involves continuous anti-thrombotic treatment, ranging from simple aspirin to therapeutic anticoagulation (INR > 3). The main threat comes from five main situations: atrial fibrillation (AF), history of deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism, cancer disease, valve implantation and coronary stent implantation [2,15]. The CHADS score2 , defined in the context of AF, provides some stratification of thromboembolic risk (Table 8.6A) and has been further refined as the CHA score2 DS2 -VASc (Table 8.6B) [3,10].

- Atrial fibrillation (AF). The annual risk of stroke ranges from 2% to 7% and 18% depending on whether the CHADS score2 is 0-2, 3-4, or ≥ 5, respectively. AF secondary to valve disease or mitral surgery is in the high-risk category.

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism. The risk of recurrence is high during the first 3 months or when combined with other factors such as cancer. Preoperatively, inferior vena cava filtering is only indicated in case of urgent intervention in the first month after the thrombo-embolic event.

- Cancerous disease. Visceral neoplasms frequently come along with a thrombogenic paraneoplastic syndrome. In addition, patients are often undergoing radio-, hormonal- or chemotherapy, and may have implanted catheters.

- Valvular prosthesis. The highest risk is represented by mechanical mitral prostheses (up to 12% thrombotic risk per year); in the aortic position, mechanical prostheses are at moderate risk if associated with other factors or at low risk if not. Biological prostheses only require anticoagulation for the first 3 months.

- Coronary stent. The presence of foreign material within a small vessel poses a great danger of platelet activation and thrombosis until the framework stent is coated with endothelium. Stent coating takes from 6 weeks (bare stents) to 6-12 months (eluting stents) or longer (high-risk stents), during which time dual antiplatelet therapy is required. Beyond that time, continuous aspirin therapy is still mandatory (see Chapter 29 Antiplatelet drugs).

- Type of surgery. Major orthopaedic surgery (THR, knee replacement) and cancer surgery have a thromboembolic risk more than 10 times higher than general surgery.

Risk of bleeding

The risk of bleeding is essentially related to three factors.

- Residual effect of the anticoagulant (or antiplatelet);

- Comorbidities of the patient;

- Type of surgery.

In chronically anticoagulated patients, the overall incidence of intraoperative bleeding is 5.1%, and the incidence of major blood loss is 2.1% [23]. The patient may have a variety of conditions that increase the likelihood of bleeding during surgery [4].

- History of spontaneous or prolonged bleeding, anaemia;

- Coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, von Willebrand disease (congenital or secondary to lymphoproliferative, carcinomatous or immunological conditions);

- Current anticoagulants or antiplatelets;

- Age > 70 years, female ;

- Renal failure ;

- Liver failure, alcoholism;

- Active cancer pathology ;

- High vascular risk (high blood pressure, history of stroke, diabetes).

The Papworth Bleeding Risk Stratification Score, developed exclusively for cardiac surgery and partially validated, is an attempt to determine in advance which patients are at high risk of bleeding. It is based on five data points, each worth 1 point [17].

- Urgent intervention ;

- Surgery other than simple coronary artery bypass grafting ;

- Aortic disease ;

- BMI > 25 ;

- Age > 75 years.

Conventional coagulation tests have a relatively low positive predictive value for the risk of intraoperative bleeding, whereas their negative predictive value is high [6]. The same applies to thromboelastography, although its predictive value is higher overall than that of conventional tests [8]. A history in relation with bleeding and anticoagulation problems is more valuable than screening laboratory tests [7].

A range of frequently consumed food interfere with coagulation and may lead to an increased risk of bleeding, particularly by potentiating the effects of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents [1]: aniseed, celery, clove, tumeric, danshen, dong quai, gingko, fenugreek, ginger, chamomile, horse chestnut, sweet clover, papain, clover, vitamin E, grapefruit. Avocado, soya, ginseng, parsley and green tea antagonise anticoagulants, especially anti-vitamin K.

The surgical procedure is generally divided into three categories according to the specific bleeding risk of the procedure [5,11,16].

- Low risk: non-haemorrhagic procedures that take place without transfusion (wall surgery, dermatology, dentistry, endoscopy, cataract).

- Intermediate risk: procedures that occasionally require blood transfusion (general surgery, laparotomy, thoracotomy, ENT, orthopaedics), endoscopy with invasive procedure, coronary angioplasty (PCI).

- High risk :

- Highly haemorrhagic procedures in which haemostasis is difficult and blood transfusion is usual (liver, aortic, cardiac surgery);

- Interventions in an enclosed space (skull, medullary canal, posterior chamber of the eye), where any haemorrhage can cause irreversible damage;

- Retroperitoneal, intrathoracic and intrapericardial procedures are considered closed surgical operations;

- Thrombolysis (stroke, acute coronary syndrome);

- Subdural or epidural loco-regional anaesthesia, lumbar puncture.

But the definition of haemorrhage is itself heterogeneous and varies according to the studies. It is often borrowed from clinical trials related to coronary stent treatment (TIMI, GUSTO, TRITON, etc). A homogeneous codification has recently been proposed by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) for non-surgical and intraoperative bleeding, which is very useful for risk assessment before surgery [12].

- Type 0: no bleeding.

- Type 1: petechiae, hypermenorrhagia, epistaxis or haemorrhoidal bleeding not requiring medical intervention.

- Type 2: bleeding that requires medical intervention, but does not meet the criteria for type 3, 4 or 5.

- Type 3: bleeding causing a fall in Hb of ≥ 30 g/L, warranting one or more transfusions, or requiring surgical revision; cardiac tamponade (3b); intracranial haemorrhage (3c).

- Type 4: Severe bleeding related to cardiac surgery with ECC: transfusion of ≥ 5 blood bags, loss of ≥ 2 L/24 hours through chest drains, intracranial haemorrhage (stroke).

- Type 5: haemorrhage resulting in death.

The risk of bleeding in patients on anti-vitamin K agents is defined by the HAS-BLED score (Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/alcohol concomitantly) [9].

- Hypertension (Not > 160 mmHg);

- Nephropathy (creatinine > 200 mcmol/L), liver disease (bilirubin, elevated transaminases );

- Stroke;

- History of major bleeding;

- Labile INR (< 60% of the time in the therapeutic range);

- Age > 65 years;

- Bleeding risk medications (antiplatelets, NSAIDs);

- Alcoholism (> 8 drinks/week)

Each element is worth 1 point.

Balance of risks

Interruption of anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy immediately puts the patient at major risk of thrombosis and/or embolism [14]. This is a serious decision that must be carefully considered, even if the aim is to reduce the operative risk by improving haemostasis. Apart from operations with a high bleeding risk, the danger represented by blood loss is generally less serious than thrombo-embolic threat. The risk of sequelae from vascular thrombosis is much greater than that from bleeding. Although less frequent, thrombosis carries a higher mortality than bleeding.

The laboratory values usually recommended for safe surgery are as follows

- INR < 1.5,

- TP > 75%,

- aPTT < laboratory standard-limit (30-40 sec depending on the lab),

- ACT < 120 sec,

- Thrombocytes ≥ 70'000 /mcL.

| Risk stratification in anticoagulated patients |

|

Perioperative management of anticoagulated surgical patients is based on the risk of bleeding if the operation is performed under anticoagulation and the risk of thrombosis if the treatment is discontinued.

The risk of thrombosis is high in cases of :

- AF with ventricular failure, hypertension, diabetes, old age or stroke

- Thromboembolic disease (especially < 3 months)

- Cancerous disease

- Mechanical valve prosthesis (mitral > aortic)

- Coronary stents (BMS < 6 weeks, DES < 6-12 months)

The surgical procedure is divided into three categories according to the risk of bleeding:

- Low risk: non-hemorrhagic procedures, no transfusion

- Intermediate risk: occasional transfusion

- Major risk: haemorrhagic procedures (difficult haemostasis, usual transfusion), interventions in an enclosed space (skull, medullary canal, posterior chamber of the eye),spinal LRA

Recommended laboratory values for bleeding surgery :

- TP > 75%, INR < 1.5

- aPTT ≤ laboratory standard

- ACT < 120 sec

- Thrombocytes ≥ 70'000 /mcL

In general, morbidity and mortality due to thrombosis is higher than to haemorrhage.

|

© CHASSOT PG, MARCUCCI Carlo, last update November 2019.

References

- BARASH PG, et al, eds. Précis d'anesthésie clinique. Paris: Arnette (Wolters Kluwer France), 2008, 1205-14

- BARON TH, KAMATH PS, McBANE RD. Management of antithrombotic therapy in patients undergoing invasive procedures. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:2113-24

- DOUKETIS JD, SPYROPOULOS AC, SPENCER FA, et al. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines, Chest 2012; 141 (2 suppl): e326S-50S

- GOMBOTZ H, KNOTZER H. Preoperative identification of patients with increased risk for perioperative bleeding. Curr Opin Anesthesiol 2013; 26:82-90

- HEIDBUCHEL H, VERHAMME P, ALINGS M, et al. European Heart Rythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Europace 2015; 17:1467-507

- KOZEK-LANGENECKER SA. Perioperative coagulation monitoring. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2010; 24: 27-40

- KOZEK-LANGENECKER SA, AFSHARI A, ALBALADEJO P, et al. Management of severe perioperative bleeding: Guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2013; 30: 270-82

- LEE GC, KICZA AM, LIU KY, et al. Does rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) improve prediction of bleedingaftercardiac surgery? Anesth Analg 2012; 115: 499-506

- LIP GY, FRISON L, HALPERIN JL, et al. Comparative validation of a novel risk score for predicting bleeding risk in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation: the HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal renal/liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/alcohol concurrently) score. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:173-80

- LIP GY, NIEUWLAAT R, PFISTERS R, et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest 2010; 137:263-72

- MAR PL, FAMILTSEV D, EZEBOWITZ MD, et al. Periprocedural management of anticoagulation in patients taking novel oral anticoagulants: Review of the literature and recommendations for specific populations and procedures. Int J Cardiol 2016; 202:578-85

- MEHRAN R, RAO SV, BHATT DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials. A consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation 2011; 123:2736-47

- TAFUR AJ, McBANE R, WYSOKINSKI WE, et al. Predictors of major bleeding in peri-procedural anticoagulation management. J Thromb Haemost 2012; 10:261-7

- TOTH P, MAKRIS M. Prothrombin complex concentrate-related thrombotic risk following anticoagulation reversal. Thromb Haemost 2012; 107:599

- VAN VEEN JJ, MAKRIS M. Management of perioperative anti-thrombotic therapy. Anaesthesia 2015; 70 (Suppl.1): 58-67

- VEITCH AM, VANBIERVLIET G, GERSCHLICK AH, et al. Endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, including direct oral anticoagulants: British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines. Gut 2016; 65:374-89

- VUYLSTEKE A, PAGEL C, GERRARD C, et al. The Papworth Bleeding Risk Score: a stratification scheme for identifying cardiac surgery patients at risk of excessive early postoperative bleeding. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011 ; 39 :924-30