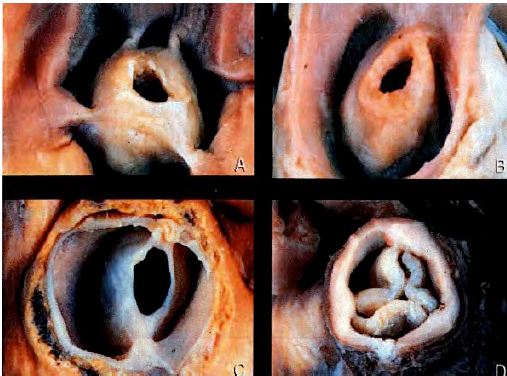

Pulmonary stenosis (S < 2 cm2 /m2), which is rare in adults, is usually congenital (commissural fusion, monocuspidity, bicuspidity) or secondary to carcinoid; the valve becomes conical (see Figure 14.61B). Stenosis may also occur 10-15 years after correction of tetralogy of Fallot with a pulmonary patch if the enlargement was insufficient. Whereas normal Vmax across the valve is 0.5 - 1.0 m/s, stenosis is characterised by accelerated flow during protosystole [1]:

- Mild stenosis: Vmax < 2 m/s ΔP max < 30 mmHg

- Moderate stenosis: Vmax 2.5 - 4 m/s ΔP max 35-60 mmHg

- Severe stenosis: Vmax > 4 m/s ΔP max > 60 mmHg (S ≤ 0.5 cm2 /m2)

Video: Major RV hypertrophy in a case of adult pulmonary stenosis.

Severe pulmonary stenosis is characterised by a thickened valve, rigid leaflets, calcifications and a dome-shaped deformation in systole. Vmax is > 4 m/s and maximum gradient > 64 mmHg. The RV is hypertrophied, including the RVOT, which is narrow. The trunk of the PA undergoes poststenotic dilatation [3].

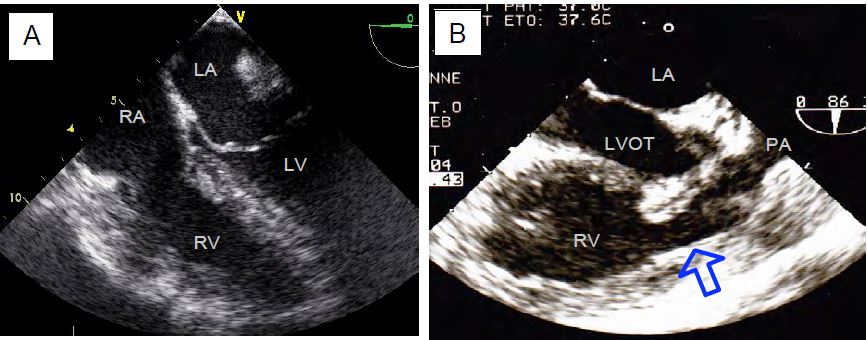

Figure 11.163: Pulmonary stenosis. A: Massive hypertrophy of the RV. B: Complex pulmonary stenosis in 90° midesophageal view by clockwise rotation of the probe from a 2-cavity view of the RV (case of adult tetralogy of Fallot). The right outflow tract is narrow and enlarged (arrow), the stenotic pulmonary valve is difficult to see in the proximal narrowing of the pulmonary artery; the RV is enlarged.

A ΔPmax ≥ 50 mmHg is a surgical indication for percutaneous valvulotomy or valve replacement [1]. The procedure involves replacement of the valve, usually with a biological valve conduit (homograft or heterograft) [3]. In a pulmonary homograft or heterograft, a maximum ΔP of up to 20 mmHg is tolerated in normal RV (Ross operation) and 30-40 mmHg in HRV (variable depending on preoperative gradient).

Video: Heterograft pulmonary valve replacement (Contegra).

The RV outflow tract is richer in with β receptors than the ventricular body. Its inotropic response to catecholaminergic stimulation is greater than that of the free wall and inflow tract. It can cause dynamic obstruction (right HOCM effect), which is common after pulmonary valve replacement for stenosis when the RV is very hypertrophied. Vmax in RVOT is 2-2.5 m/s, gradient > 20 mmHg [2]. Treatment consists of reducing catecholamines β , hypervolaemia, relative hypoventilation (increased PAR) and and β blockers (bolus esmolol).

| Hemodynamics sought in pulmonary stenosis |

| High, stable right preload

Systemic vasoconstriction Full - normocardium - closed |

© CHASSOT PG, BETTEX D, August 2011, last update November 2019

References

- BRUCE CJ, CONNOLLY HM. Right-sided valve disease deserves a little more respect. Circulation 2009; 119:2726-34

- DENAULT AY, CHAPUT M, COUTURE P, et al. Dynamic right ventricular outflow tract obstruction in cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006; 132:43-9

- NISHIMURA RA, OTTO CM, BONOW RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation 2014; 129:e521-e643