Mitral stenosis is a disease that develops very slowly. Symptoms do not appear until 20 to 40 years after the initial onset of ARF, and it takes another ten years or so for them to become bothersome. They take the form of dyspnoea, which often occurs abruptly with exertion, pregnancy or any condition requiring an increase in cardiac output and/or rate, such as thyrotoxicosis, anaemia or transition to atrial fibrillation. Subsequently, fatigue, orthopnea and haemoptysis reflect low output and left-sided congestion. These manifestations of left-sided failure are progressively supplemented by those of right-sided congestion (peripheral oedema, ascites) as pulmonary hypertension induces right-sided dilatation and secondary tricuspid insufficiency. The presentation is typical: mitral facies, oedematous, cold and cyanotic extremities, dilated and pulsatile jugular veins, ascites, bradycardic and irregular arterial pulse. Atrial dilatation and fibrillation may occur in otherwise asymptomatic patients, leading to thromboembolism in 14% of cases [7]. Without treatment, 10-year survival is >80% in asymptomatic patients and 50-60% in symptomatic patients. However, when exertion is no longer possible (NYHA class III-IV), survival is only 0-15% [6,8].

In the Third World, economic and social conditions accelerate the progression of the disease. In industrialised countries, the disease rarely reaches extreme levels, but the incidence of coronary artery disease is significant, with 23% of patients presenting with more or less silent ischaemia [5]. This raises the issue of coronary angiography in the preoperative evaluation. The current trend is to be more invasive, as the association of coronary artery disease significantly worsens the prognosis of mitral valve disease. However, the combination of coronary revascularisation and mitral valve replacement (MVR) has a significantly higher mortality than MVR alone: 7-12% compared with 3-5% [1,3].

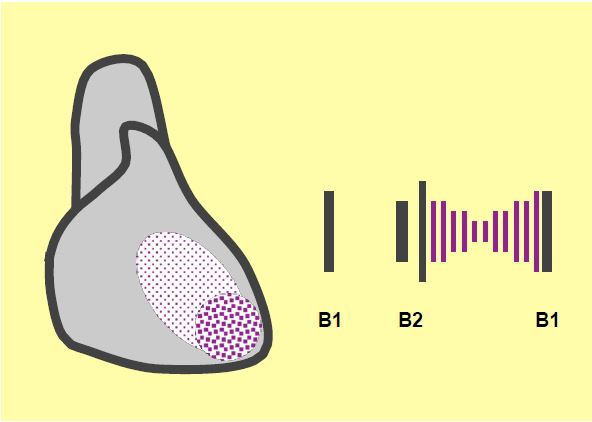

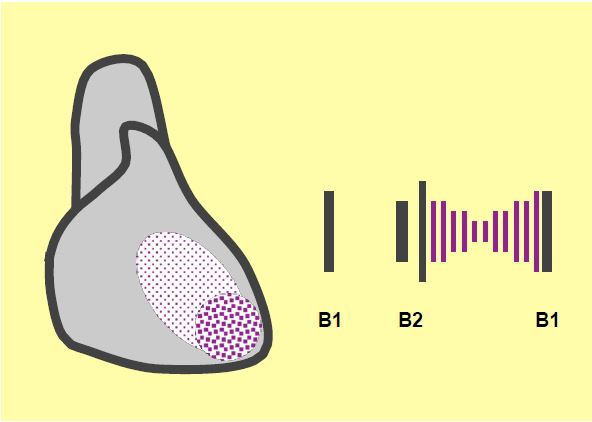

On auscultation, B1 is accentuated, followed by a snap of the mitral orifice and a diastolic roll with a presystolic crescendo (Figure 11.91) [2]. The ECG shows a vertical axis, broad and bifid P waves in I and II (> 0.12 sec), biphasic in V1 and V2, signs of right ventricular hypertrophy in pulmonary hypertension and atrial fibrillation in 40% of cases. The chest x-ray shows that the LA is sometimes gigantically dilated.

There is no curative treatment other than mechanical relief of the mitral regurgitation. Medical treatment consists of three elements [6,4,9].

- Rhythm slowing (β blockers, anti-calcemics) and reduction of pulmonary congestion (hydro-saline restriction, diuretics, nitrate derivatives).

- Treatment of atrial fibrillation: electrical cardioversion, amiodarone, slowing of the ventricular response (β blockers, digoxin).

- Anticoagulation (anti-vitamin K agents for INR 2-3) in AF, previous stroke, atrial thrombus or dilatation of the LA with high spontaneous contrast.

Figure 11.91: Murmur of mitral stenosis: decrescendo roll with presystolic enhancement, burst of B1 at the apex, opening snap after B2.

| Clinical picture of mitral stenosis |

| Long asymptomatic course from the onset of ARF (20-40 years), but very limited survival once symptoms appear: dyspnoea, fatigue, arrhythmia (AF). Symptoms often occur when there is an increase in cardiac output: sport, pregnancy, thyrotoxicosis, etc.

Medical treatment (non-curative):

- Slow down the ventricular rate and reduce congestion.

- Treatment of AF

- Anticoagulation (AVK) for AF, stroke or risk of thromboembolism

|

© CHASSOT PG, BETTEX D, August 2011, last update November 2019

References

- BAUMGARTNER H, FALK V, BAX JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017; 38:2739-86

- BRAUNWALD E. Valvular heart disease. In: BRAUNWALD E. ed. Heart disease. Philadelphia, WB Saunders Co, 1997, 1007-76

- GILLINOV AM. Is ischemic mitral regurgitation an indication for surgical repair or replacement? Heart Fail Rev 2006; 11:231-9

- IUNG B, GOHLKE-BÄRWOLF C, TORNOS P, et al. Recommendations on the management of the asymptomatic patient with valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2002; 23:1253-66

- MATTINA CJ, GREEN SJ, TORTOLANI AJ, et al. Frequency of angiographically significant coronary arterial narrowing in mitral stenosis. Am J Cardiol 1986; 57:802-9.

- NISHIMURA RA, OTTO CM, BONOW RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation 2014; 129:e521-e643

- RAMSDALE DR, ARUMUGAN N, SINGH SS, et al. Holter monitoring in patients with mitral stenosis and sinus rhythm. Eur Heart J 1997; 8:164-70

- SELZER A, COHN KE. Natural history of mitral stenosis: A review. Circulation 1972; 45:878-90

- VAHANIAN A, ALFIERI O, ANDREOTTI F, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). The Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2012; 33:2451-96