Combination of anticoagulant and antiplatelet

Thrombin activates both fibrin formation and platelet aggregation; it is a bridge between coagulation and platelet aggregation systems. But thrombocytes have their own activation systems, and their many receptors can be blocked by different substances (Figures 8.12 and 8.13) (Tables 8.11 and 8.12). Although not anticoagulants per se, antiplatelet agents (APAs) inhibit thrombocyte aggregation and inhibit to varying degrees the formation of the "white thrombus" which is basis of clot in arterial vascular lesions (e.g. atheromatous plaque rupture) [1]. The topic is detailed in Chapter 29 Antiplatelets.

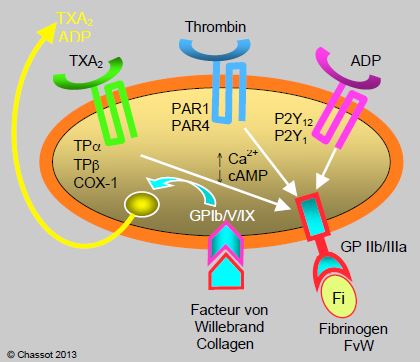

Figure 8.12: Several types of receptors are located on the surface of a platelet. During endothelial injury, von Willebrand factor (vWF) and collagen activate the GP Ib/V/IX receptor. This results in the release of thromboxane A2 (TXA2 ), ADP, thrombin and serotonin. These substances will activate the corresponding receptors on the platelet and neighbouring thrombocytes (TPa andb , P2Y1 and P2Y12 , PAR1 and PAR4). Stimulation of these receptors induces an increase in intracellular Ca2+ and a decrease in cyclic AMP, which leads to activation of the GP IIb/IIIa receptor; this binds to fibrinogen, which agglutinates several platelets together, and to vWF, which anchors the platelet to the wall. PAR: protease-activated receptor. TP: thromboxane/prostanoid.

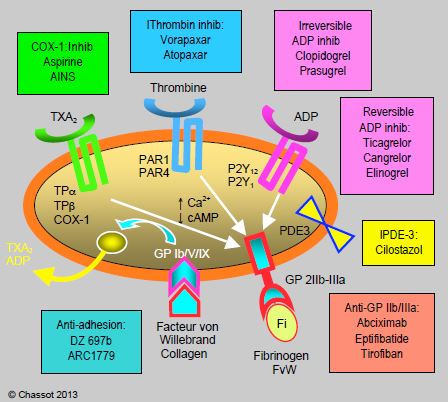

Figure 8.13: The different categories of antiplatelet agents, classified according to the receptor blocked. Inhib: inhibitors. IPDE: phospho-diesterase inhibitor. vWF: von Willebrand factor. Fi: fibrinogen.

Sometimes ongoing anticoagulant therapy for prosthetic valve disease or atrial fibrillation (AF) must be combined with dual antiplatelet therapy because of a recent coronary event. AF may also occur during an acute coronary syndrome and require anticoagulation in addition to antiplatelet therapy. This triple therapy obviously carries an increased bleeding risk: the bleeding rate is increased by 1.6 to 4 times compared to dual therapy [5]. Therefore, only clopidogrel is relevant in this situation, as ticagrelor and prasugrel are too bleeding-prone. On the other hand, triple therapy is limited to 3-6 months [13,14]. The combination of antiplatelets with a new oral anticoagulant such as dabigatran is less bleeding than the combination with warfarin [2]. In situations where risk of blood loss is high, it is probably more effective to suppress aspirin: the WOEST study compared the combination of an anticoagulant and clopidogrel with or without aspirin [4]. The risk of bleeding was significantly reduced without aspirin (HR 0.36), while the risk of coronary thrombosis showed no significant difference. These results were confirmed by a Danish registry of 12,165 patients [9]. It therefore seems possible to dispense with aspirin in patients on anticoagulants requiring antiplatelet therapy, at least when the risk of bleeding is high and the coronary status is stable [3].

The addition of rivaroxaban to dual antiplatelet therapy tends to reduce cardiovascular risk after acute coronary syndrome (HR 0.69), but at the cost of a 2-5 fold increase in bleeding risk directly proportional to the dose of anticoagulant (5-20 mg/d) [10]. The addition of a low dose of rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) reduces the rate of infarction, stroke, mortality (HR 0.84) and stent thrombosis (HR 0.68), but still at the cost of a slight increase in the risk of intracranial bleeding [11]. In contrast, the rate of bleeding was reduced (OR 0.59) with no change in thrombotic risk when a standard dose of rivaroxaban (15 mg/d) was combined with a single P2Y inhibitor12 [7]. Newer oral anticoagulants are likely to play an increasingly important role after coronary revascularisation; several ongoing studies are exploring different combinations of these agents with a reduction in antiplatelet agents, including aspirin [6].

This obviously raises the question of perioperative management of these patients. Unfortunately, no clinical data are available to adress this question with certainty. Nevertheless, the following attitude can be proposed.

- Dismissal of all elective operations during triple therapy;

- For life-saving or emergency surgery, stop clopidogrel 5 days and rivaroxaban 24 hours (2x 2.5 mg/d) to 72 hours (15 mg/d) before surgery;

- Continuation of aspirin depending on the operative bleeding risk;

- Abstention from loco-regional spinal anaesthesia;

- Evaluate the residual effect of the substances preoperatively with a platelet aggregability test and an anti-Xa test.

Statins

Statins are 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, widely used for their lipid-lowering, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and atheromatous plaque-stabilising effects (see Chapter 3 Statins). But statins still have direct effects on both coagulation and platelet aggregability [15].

- Inhibition of tissue factor (TF) activity and decreased synthesis of factor Va;

- Activation of thrombomodulin and the coagulation inhibitory protein C pathway;

- Inhibition of thromboxane A formation1 and activation of NO synthesis in platelets.

In several clinical situations, statins have indeed demonstrated a significant reduction in cardiovascular risk (44-63%), independent of other therapeutic conditions: coronary angioplasty, acute coronary syndrome, deep vein thromboembolism [8,12]. However, these are mostly studies involving high doses of statins, which tend to increase the risk of haemorrhagic stroke.

| Anitplatelets and statins |

|

Antiplatelet agents inhibit thrombocyte aggregation and slow down white thrombus formation.

Combination of anticoagulation and antiplatelets (e.g. triple therapy for AF and coronary stent): prefer clopidogrel, prescribe minimal doses of anticoagulant, preferably NOACs, possibly discontinue aspirin. Maximum duration of triple therapy: 3-6 months.

Statins moderately inhibit tissue factor activity and thromboxane A1 formation.

|

© CHASSOT PG, MARCUCCI Carlo, last update November 2019.

References

- BECATTINI C, AGNELLI G, SCHENONE A, et al. Aspirin for preventing the recurrence of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1959-67

- DANS AL, CONNOLLY SJ, WALLENTIN L, et al. Concomitant use of antiplatelet therapy with dabigatran or warfarin in the Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial. Circulation 2013; 127:634-40

- DEWILDE WJM, JANSSEN PWA, VERHEUGT FWA, et al. Triple therapy for atrial fibrillation and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:1270-80

- DEWILDE WJM, OIRBANS T, VERHEUGT FWA, et al for the WOEST study investigators. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 381:1107-15

- FITCHETT D, VERMA A, EIKELBOOM J, et al. Prevention of thromboembolism in the patient with acute coronary syndrome and atrial fibrillation: the clinical dilemna of triple therapy. Curr Opin Cardiol 2014; 29:1-9

- GARGIULO G, WINDECKER S, VRANCKX P, et al. A critical appraisal of aspirin in secondary prevention. Is less more ? Circulation 2016; 134:1881-906

- GIBSON CM, MEHRAN R, BODE C, et al. Prevention of bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:2423-34

- HULTEN E, JACKSON JL, DOUGLAS K, et al. The effect of early, intensive statin therapy on acute coronary syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1814-21

- LAMBERTS M, GISLASON GH, OLESEN JB, et al. Oral anticoagulation and antiplatelets in atrial fibrillation patients aTFer myocardial infarction and coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62:981-9

- MEGA JL, BRAUNWALD E, MOHANAVELU S, et al. Rivaroxaban versus placebo in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ATLAS ACS-TIMI 46): a randomised, double-blind, phase II trial. Lancet 2009; 374:29-38

- MEGA JL, BRAUNWALD E, WIVIOTT SD, et al. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:9-19

- PATTI G, CANNON CP, MURPHY SA, et al. Clinical benefit of statin pretreatment in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a collaborative patient-level meta-analysis of 13 randomized studies. Circulation 2011; 123:1622-32

- VALGIMIGLI M, BUENO H, BYRNE RA, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg 2017; 00:1-45

- VALGIMIGLI M, BUENO H, BYRNE RA, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Hesrt J 2018; 39:213-54

- VIOLI F, CALVIERI C, FERRO D, PIGNATELLI P. Statins as antithrombotic drugs. Circulation 2013; 127:251-7