Anatomy

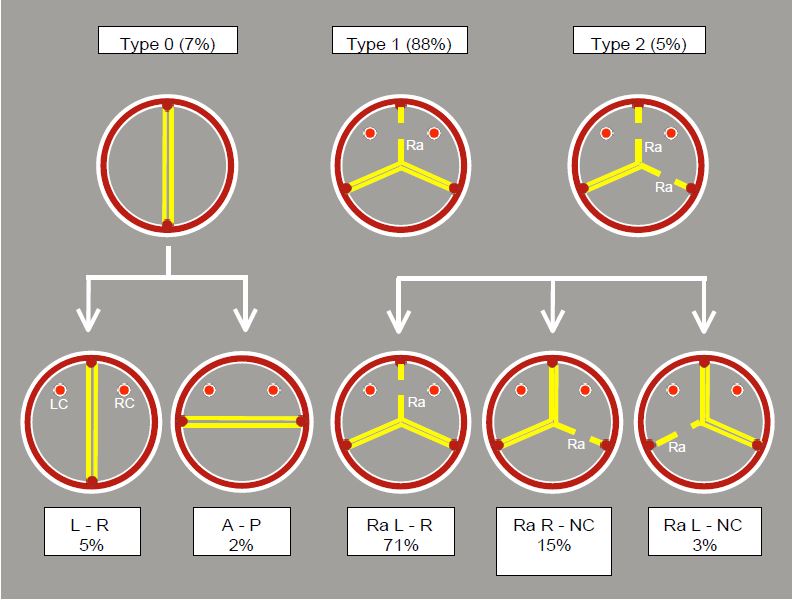

Bicuspid aortic valve disease may progress to stenosis (75% of cases) or insufficiency (25% of cases) and is therefore included under the heading of aortic disease. Aortic bicuspid disease is the second most common congenital heart disease after patent foramen ovale. It affects 1-2% of the general population, but only becomes symptomatic between the ages of 30 and 50 [5]. There are several anatomical variants of bicuspid valve disease. Historically, there were two categories: true bicuspidism (2 commissures and 2 cusps, no raphe) and acquired bicuspidism (3 commissures, 3 cusps, 2 of which are fused by a raphe) (see Aortic valve, Nosology). In the last decade, the Sievers classification, based on the number and position of the raphe (fusion between two cusps), has been preferred (Figure 11.149) [8,9].

Figure 11.149: Sievers classification of bicuspidia and its prevalence. This classification is based on the number of raphe (shaded). Ra: raphe. LC: left coronary artery. RC: right coronary artery [9].

- Type 0: Presence of 2 commissures and 2 approximately equal cusps, absence of raphe; this type corresponds to the old true bicuspidity. It accounts for 7% of cases. The two leaflets have a right-left orientation (2/3 of cases) or an antero-posterior orientation (1/3 of cases). In systole, the opening is oval, but the leaflets do not meet the wall of the sinus of Valsalva. In diastole, prolapse of one leaflet is common.

- Type 1: Presence of 3 commissures but 2 functional cusps because two of them are fused by a raphe (88% of cases). The free edge of the fused double leaflet exceeds that of the single leaflet and tends to prolapse. There are three variations of this type.

- Fusion of the right and left cusps; the opening occurs between the non-coronal cusp and the block of two coronal cusps fused by a raphe. This is the most common case (71% of bicuspids). The arrangement of the cusps means that the fused cusp occupies 210° of the circumference and the non-coronal cusp 150°.

- Fusion between the right cusp and the non-coronal cusp (15% of cases).

- Fusion between the left cusp and the non-coronal cusp (3% of cases).

- Type 2: Fusion between the left and right cusps, with fusion between the latter and the non-coronal cusp; there are 2 raphe. This is the rarest type (5% of cases). Opening between the left and non-coronal cusps is only possible via a very narrow orifice, which causes very early stenosis symptoms .

When a bicuspid valve calcifies, calcium deposits concentrate in the raphe and at the base of the leaflets (see Figure 11.101).

Bicuspid aortic valve disease is associated with several abnormalities of the thoracic aorta, including coarctation, aneurysm and dissection. What these conditions have in common is a fibrillin-1 defect that leads to degeneration of the aortic media [3]. Carriers of bicuspidism have an 85-fold higher rate of ascending aortic aneurysm and an 8-fold higher rate of dissection than the general population [7]. The aortic root and sinuses of Valsalva are dilated in a quarter of cases.

Echocardiography

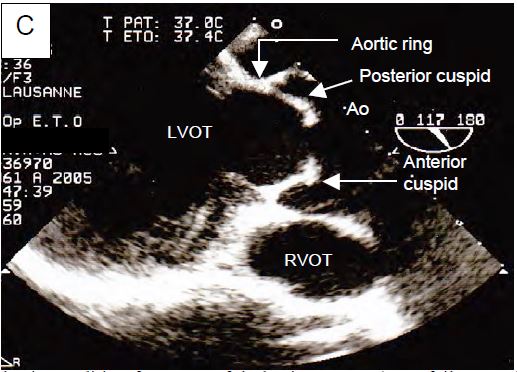

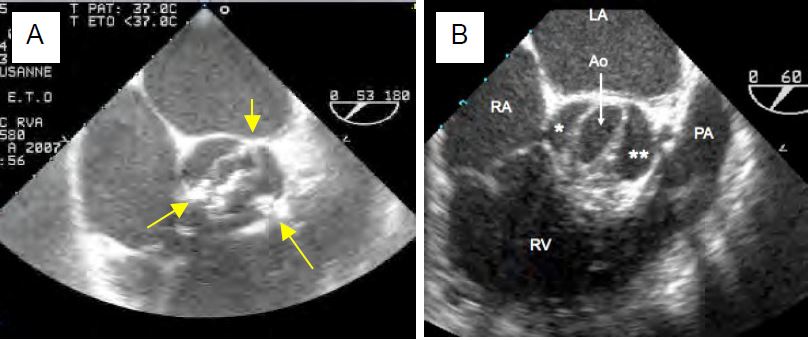

In the 40° short-axis view, the orifice is slit-shaped, elliptical or banana-shaped, depending on the configuration. In type 0 there are only 2 commissures separated by about 180°. In types I and II, 3 commissures are clearly visible, arranged at about 120° to each other, but often staggered. In bicuspids acquired by calcification and secondary fusion of two cusps, the 3 commissures are equidistant. In the 120-140° long-axis view, bicuspid valves show classic doming during systole because the valve opening is restricted but the leaflet body remains sufficiently flexible to bulge outwards (Figure 11.150).

Figure 11.150: TEE images of bicuspid aortic valve. A and B: short axis. In A, the valve is calcified and stenotic; it has 3 commissures (yellow arrows) with fusion between the right and left coronal cusps. In B there are only 2 commissures (anterior and posterior). C: Long axis. The free edge of the cusps is too short to allow them to reach their physiological position in systole; they are held in an intermediate position, giving a domed appearance.

- Levelling of the free edges of the cusps by folding or resection;

- Release of the raphe to restore mobility to the cusps (tricuspidisation);

- Annuloplasty to stabilise the ventriculo-aortic junction (ring ≤ 27 mm).

- Ascending aortic diameter ≥ 5.5 cm in an asymptomatic patient;

- Ascending aortic diameter ≥ 5.0 cm in an asymptomatic patient with risk factors for dissection;

- Ascending aortic diameter ≥ 4.5 cm in a patient undergoing surgery for severe aortic stenosis or insufficiency.

|

Aortic bicuspidity

|

|

Coarctation of the aorta is common. It can develop into stenosis (75% of cases) or insufficiency (25% of cases). There are 3 anatomical types:

- Type 0: 2 cusps and 2 commissures, approximately equal, with R-L or A-P symmetry.

- Type 1: presence of a raphe fusing 2 cusps and leaving the 3rd free; fusion between the right and left coronary arteries.

and left coronary cusps is the most common case.

- Type 2: Presence of 2 raphae, with a single cusp opening and closing the valve.

Bicuspid insufficiency is very often associated with aneurysmal dilatation of the aortic root and/or ascending aorta, dissection or coarctation.

|

© CHASSOT PG, BETTEX D, August 2011, last update November 2019

References

- ASHIKHMINA E, SUNDT TM, DEARANI JA, et al. Repair of the bicuspid aortic valve: a viable alternative to replacement with a bioprosthesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010; 139:1395-401

- BAVARIA JE, KOMIO CM, RHODE T, et al. Can the bicuspid aortic valve be spared? The con position, with caveats and nuances. Texas Heart Inst J 2013; 40:544-6

- FEDAK PW, BARKER AJ, VERMA S. Year in review: bicuspid aortopathy. Curr Opin Cardiol 2016; 32:132-8

- HIRATZKA LF, CREAGER MA, ISSELBACHER EM, et al. Surgery for aortic dilatation in patients with bicuspid aortic valves. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67:724-31

- IUNG B, BARON G, BUTCHART EG, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: the Euro Heart Survey on valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2003; 24:1231-43

- MAZZIELLI D, PFEIFFER S, RANKIN JS, et al. A regulated trial of bicuspid aortic valve repair suported by geometric annuloplasty. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 99:2010-6

- MICHELENA HI, DELLA CORTE A, PRAKASH SK, et al. Bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy in adults: incidence, etiology and clinical significance. Int J Cardiol 2015; 201:400-7

- RIDLEY CH, VALLABHAJOSYULA P, BAVARIA JE; et al. The Sievers classifiction of the bicuspid aortic valve for the perioperative echocardiographer: the importance of valve phenotype for aortic valve repair in the era of the functional aortic annulus. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2016; 30:1142-51

- SIEVERS HH, SCHMIDTKE C. A classification system for the bicuspid aortic valve from 304 surgical specimens. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007; 133:1228-33