Age is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications (OR 2.99) and mortality (OR 1.88) [11]. On average, operative mortality in cardiac surgery doubles after the age of 70 and quadruples after the age of 90. However, age is probably not a risk factor in itself. Rather, it is a marker for a high prevalence of comorbidities. The cardiovascular lesions of ageing are the result of repeated or continuous exposure to adverse factors, whether avoidable or not, the duration of which is simply measured by age (see Chapter 21, The elderly patient) [15].

Physiological age, defined by the degree of clinical degeneration, can be very different from nominal age. This is well expressed by the concept of patient frailty. Frailty represents extreme vulnerability, resulting in the inability of patients to maintain homeostasis in the face of changes in their environment, both physical and psychological. It is related to the cumulative effect of the decline in many systems with age. Its prevalence is 16% between the ages of 80 and 84 and 26% over the age of 85 [4]. This loss of resilience erodes physiological reserves to such an extent that minimal stressors can trigger disproportionate changes in clinical status. The diagnosis of frailty is very important because these patients are severely compromised by the high stress of surgery, although their chronological age is not in itself a contraindication [4]. Frailty is often associated with cardiovascular disease (OR 4.1) [2]. Clinical symptoms include weakness, fatigue, repeated falls, inactivity, weight loss, malnutrition, anaemia, shrinkage, dependence on others for daily needs, slow walking (> 6 sec per 5 m), depression and cognitive impairment. This can be used to create an index, a high value of which is an independent predictor of the risk of surgery and increases mortality by a factor of 2 to 4 [3]. The hazard ratio (HR) associated with frailty is 2.6 - 3.7 for bypass surgery and 3.2 for TAVI (transcatheter aortic valve implantation) [2,13].

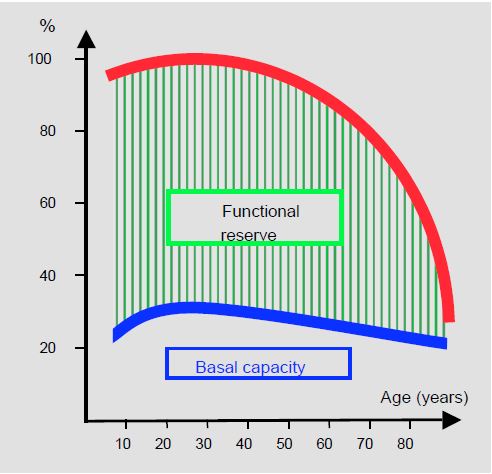

Although they perform normally at rest, older people have lost their functional reserve to ensure sustained effort and to respond to external stress. With a functional loss of 1%/year for most of their organs from the age of 35, they have no reserves when demand increases; no compensation beyond baseline conditions is possible (see Figure 21.11) [5]. This loss of adaptive capacity has three clinical consequences.

- The clinical state at rest does not predict behaviour under stress; a patient who is well-balanced on a daily basis will decompensate rapidly at the slightest complication.

- No significant compensation is possible beyond the basic conditions.

- Major surgery is possible as long as homeostasis is rigorously maintained and no complications occur.

Surgery in the elderly therefore requires the anaesthetist to adopt a proactive attitude and invest a great deal of time and effort. He or she must ensure that no prolonged abnormalities such as hypotension, hypertension, tachycardia, acidosis, hyperglycaemia, hypoxaemia or anaemia develop. Any changes must be corrected as soon as they occur, because what is tolerable in the young is no longer so in the old. Elderly patients no longer have the functional reserve to compensate for major deviations, so the anaesthetist must be sharp and correct as quickly as possible any significant change that takes the patient away from his or her basic equilibrium.

Figure 21.11: Age-related changes in functional reserve. Basal capacity is little changed, but maximum functional capacity is dramatically reduced; patients have lost all ability to adapt to changes in load conditions or to the cardiodepressant effect of substances [from Cook DJ, Rooke GA. Priorities in perioperative geriatrics. Anesth Analg 2003; 96:1823-36].

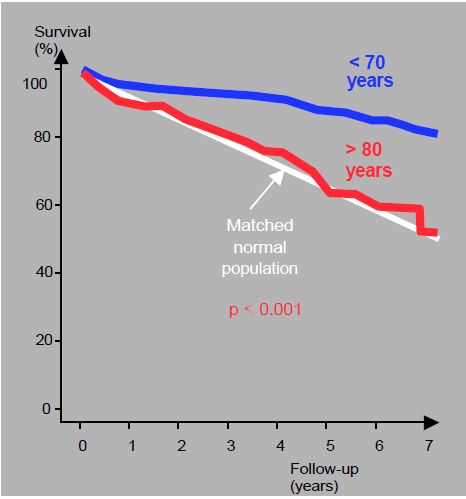

As a result, major operations such as heart surgery are only possible if they go smoothly. The slightest complication is a recipe for disaster. Clinically, this means high operative and immediate post-operative mortality (< 30 days), but excellent 5-year survival if the operation is successful. Overall mortality in octogenarians is more than double that of sexagenarians [8,17].

- Aortic valve replacement (stenosis) 6% (< 60 years: 1-3%);

- Mitral valve replacement (regurgitation) 18% (< 60 years: 2-4%);

- Mitral valve replacement (stenosis) 25% (< 60 years: 5%).

In nonagenarians, the average operative mortality rate is 13% [14]. Calculation of the EuroSCORE predicts a mortality rate of 15-25% in patients aged > 75 years. The rate of post-operative complications is 20-35% in octogenarians and 42% in non-agenarians [14,17]. Despite operative mortality being more than double that of younger patients, the 5-year survival rate of octogenarians after valve replacement is excellent and identical to that of the matched normal population (see Figure 21.14). For aortic valve replacement, for example, 66% are > 80 years and 86% < 70 years [6]. Surgery is therefore curative, even if it is risky, because these survival rates are equivalent to those of people of the same age who do not have heart disease. Furthermore, survival benefit is not the primary goal for elderly patients, who are more sensitive to the ability to maintain their independence and activity than simply extending their lives [8].

Transcatheter valve surgery is particularly well suited to the elderly. In high-risk cases, the results of aortic valve replacement (TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation) are clearly superior to those of ECC surgery in terms of mortality, stroke and postoperative morbidity (see Chapter 10, TAVI) [1]. TAVI also compares favourably with AVR in intermediate risk cases [12]. For example, in high-risk octogenarians deemed inoperable on bypass, operative mortality at 1 month and 1 year is 9.7% and 19.8%, respectively, and the stroke rate is 4.1% [7]. Given the short life expectancy of these patients, the long-term durability of the implanted bioprosthesis is not a concern. Percutaneous mitral valve repair (MitraClip™) provides a satisfactory repair in approximately 90% of cases (see Chapter 10, Percutaneous Mitral Valve Repair). When compared with surgical repair, MitraClip™ has a higher technical failure rate (3.2% vs. 0.6%), but significantly lower operative mortality (3.3% vs. 16.2%), stroke rate (1.1% vs. 4.5%) and bleeding risk (4.2% vs. 59%) [10]. Although it does not offer the same quality of correction as open surgery (recurrence rate 25% vs 5%), this percutaneous technique allows a reduction in MI of approximately 2-3 degrees (out of 4) with low operative risk in severely compromised patients, whose operative mortality would be >20% and complication rate >50% if ECC were performed [8,16].

Figure 21.14: Long-term survival of patients in their eighties (red curve) undergoing aortic valve replacement for tight stenosis. Although survival at 5 years is lower than in patients under 70 years of age (blue curve), it is comparable to the life expectancy of healthy individuals of the same age (white line) [after Filsoufi F, et al. Excellent early and late outcomes of aortic valve replacement in people aged 80 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56:255-61].

| Heart valve surgery in the elderly |

| An increasing proportion of surgical patients are elderly. Age is a risk factor associated with the duration of comorbidities.

The success of cardiac surgery in the elderly depends on rigorous maintenance of homeostasis and the absence of operative complications. Given the loss of functional reserve, any incident is a recipe for disaster. The anaesthetist must therefore immediately correct any significant deviation in haemodynamic, respiratory, metabolic or haematological variables. Operative mortality > 75 years is 2 times higher than < 60 years; > 85 years it is 4 times higher. However, once the high-risk perioperative period is over, the long-term life expectancy of AVRs is the same as that of healthy people of the same age. Minimally invasive and/or non-ECC procedures are particularly suitable for the elderly (TAVI, MitraClip™) |

References

- ADAMS DH, POPMA JJ, REARDON MJ, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1790-8

- AFILALO J, ALEXANDER KP, MACK MJ, et al. Frailty assessment in the cardiovascular care of older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:47-62

- BAGNALL NM, FAIZ O, DARZI A, ATHANASIOU T. What is the utility of preoperative frailty assessment for risk stratification in cardiac surgery? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013; 17:398-402

- CLEGG A, YOUNG J, ILIFFE S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013; 381:752-62

- COOK DJ, ROOKE GA. Priorities in perioperative geriatrics. Anesth Analg 2003; 96:1823-36

- FILSOUFI F, RAHMANIAN PB, CASTILLO JG, et al. Excellent early and late outcomes of aortic valve replacement in people aged 80 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56:255-61

- GILARD M, ELTCHANINOFF H, IUNG B, et al. Registry of transcatheter aortic-valve implantation in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1705-15

- KODALI SK, VELAGAPIDI P, HAHN RT, et al. Valvular heart disease in patients ≥ 80 years of age. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71:2058-72

- NKOMO VT, Gardin JM, SKELTON TN, et al. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet 2006; 368:1005-11

- PHILIP F, ATHAPPAN G, TUZCU EM, et al. MitraClip for severe symptomatic mitral regurgitation in patients at high surgical risk: a comprehensive systematic review. Cathet Cardiovasc Interv 2014; 84:581-90

- RANKIN JS, HAMMIL BG, FRERGUSON B, et al. Determinants of operative mortality in valvular heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006; 131:547-57

- REARDON MJ, VAN MIEGHEM NM, POPMA JJ, et al, for the SURTAVI Invesitgators. Surgical or transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:1321-31

- SEPEHRI A, BEGGS T, HASSAN A, et al. The impact of frailty on outcomes after cardiac surgery. A systematic review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 148:3110-7

- SPEZIALE G, NASSO G, BARATTONI MC, et al. Operative and middle-term results of cardiac surgery in nonagenarians. A bridge toward routine practice. Circulation 2010; 121:208-13

- WARD SA, PARIKH S, WORKMAN B. Health perspectives: International epidemiology of ageing. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2011; 25:305-17

- ZAMORANO JL, BADANO LP, BRUCE C, et al. EAE/ASE recommendations for the use of echocardiography in new transcatheter interventions for valvular heart disease. Eur J Echocardiogr 2011; 12:557-84

- ZINGONE B, GATTI G, RAUBER E, et al. Early and late outcomes of cardiac surgery in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg 2009; 87:71-8