In addition to coarctation, various anomalies may occur in the aortic arch: patent ductus arteriosus, aortopulmonary fistulas, coronary artery anomalies.

Patent ductus arteriosus

Normally, the ductus arteriosus closes within hours of birth. However, it may remain patent due to premature birth or hypoxaemia. In some malformations, it is the only source of blood flow for the pulmonary artery (pulmonary atresia) or aorta (hypoplastic or interrupted aortic arch). It causes L-to-R shunting, overloading the LV and potentially resulting in its failure. Long-term patency of a ductus arteriosus with a large diameter causes pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). If PAH reaches similar pressure levels to those in the aorta, shunting becomes bidirectional even if pulmonary diastolic pressure remains lower than systemic diastolic pressure. In neonates, a large ductus arteriosus diverts blood from the abdominal viscera and may cause mesenteric necrosis. If required, the ductus arteriosus is kept open with an infusion of prostaglandin E1 (Prostine®) or closed with indometacin.

Surgery is not indicated for a small silent patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) [4]. It is indicated if the murmur is audible, if the LV is subjected to volume overload, or if the patient has a history of endocarditis. Shunting must be exclusively L-to-R and the PVR/SVR ratio must be under 0.4. If shunting is bidirectional, banding is the only possible means of reducing the flow. This procedure is increasingly performed percutaneously (Gianturco or Gianturco-Grifka coils, Amplatzer duct occluder) or by thoracoscopy. Ligation of the patent ductus arteriosus through a high left thoracotomy is currently only indicated for premature infants and cases where the patent ductus arteriosus is too wide, calcified or twisted to be closed via the endovascular route. In premature infants, it is the same size as the PA or descending aorta. It is therefore easy to ligate the wrong vessel. Monitoring of SpO2 and pressure in the lower limb immediately alerts the surgeon of such an error. Lesion of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is always possible.

Two different sets of patients undergo surgery for ligation of their ductus arteriosus

Patent ductus arteriosus

Normally, the ductus arteriosus closes within hours of birth. However, it may remain patent due to premature birth or hypoxaemia. In some malformations, it is the only source of blood flow for the pulmonary artery (pulmonary atresia) or aorta (hypoplastic or interrupted aortic arch). It causes L-to-R shunting, overloading the LV and potentially resulting in its failure. Long-term patency of a ductus arteriosus with a large diameter causes pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). If PAH reaches similar pressure levels to those in the aorta, shunting becomes bidirectional even if pulmonary diastolic pressure remains lower than systemic diastolic pressure. In neonates, a large ductus arteriosus diverts blood from the abdominal viscera and may cause mesenteric necrosis. If required, the ductus arteriosus is kept open with an infusion of prostaglandin E1 (Prostine®) or closed with indometacin.

Surgery is not indicated for a small silent patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) [4]. It is indicated if the murmur is audible, if the LV is subjected to volume overload, or if the patient has a history of endocarditis. Shunting must be exclusively L-to-R and the PVR/SVR ratio must be under 0.4. If shunting is bidirectional, banding is the only possible means of reducing the flow. This procedure is increasingly performed percutaneously (Gianturco or Gianturco-Grifka coils, Amplatzer duct occluder) or by thoracoscopy. Ligation of the patent ductus arteriosus through a high left thoracotomy is currently only indicated for premature infants and cases where the patent ductus arteriosus is too wide, calcified or twisted to be closed via the endovascular route. In premature infants, it is the same size as the PA or descending aorta. It is therefore easy to ligate the wrong vessel. Monitoring of SpO2 and pressure in the lower limb immediately alerts the surgeon of such an error. Lesion of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve is always possible.

Two different sets of patients undergo surgery for ligation of their ductus arteriosus

- In neonates, a patent ductus arteriosus causes pulmonary overload and patients cannot be withdrawn from ventilation. Surgical ligation is indicated if indomethacin does not induce closure of the PDA. PEEP restricts pulmonary blood flow, but premature lungs are vulnerable to barotrauma. Since these infants have congestive heart failure, fluid restriction is required. Once the PDA is ligated, the circulation is overloaded by the excess volume previously mobilised by the shunt. The loss of connection with the low-pressure pulmonary circuit immediately increases LV afterload and adds pressure overload to volume overload. Since these infants are very frail, anaesthesia is provided by a fentanyl-midazolam combination.

- In older children, a patent ductus arteriosus is often discovered by chance. However, if allowed to persist, it may cause PAH. The ligation procedure is simple (left lateral thoracotomy) and requires no specific monitoring except SpO2 and pressure cuffs on the upper and lower limbs. With patients aged over 10 years, it is usually possible to use a double lumen tube (28 or 32 Fr) as one-lung ventilation facilitates surgery. Anaesthesia is based on a combination of fentanyl (10-15 mcg/kg) or remifentanil (0.5-1.0 mcg/kg) and sevoflurane (1-2%). An epidural or paravertebral block enables extubation on the operating table and ensures maximum postoperative comfort.

Ligation of the PDA immediately prompts a rise in systemic diastolic pressure, which was previously low. It also causes circulating volume overload since volume that had previously been diverted to the lungs is reintroduced into the circulation. By setting up two pressure cuffs, one on the right arm and the other on a lower limb, it is possible to measure any coarctation effect caused by ligating the PDA.

The most common complications are LV failure, ligation of the wrong vessel, lesions of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and secondary recanalisation.

| Patent ductus arteriosus |

| L-to-R shunt overloading the LV and potentially leading to PAH in the long term Two possible scenarios: - Neonates: emergency ligature because of congestive failure of the LV and pulmonary overload - Children: risk of PAH Anaesthesia - Pulse oximeter and pressure cuff on the right arm and lower limb - Rapid extubation - Epidural possible > 5 years - Post-ligation: increased diastolic pressure and risk of congestive overload of the LV |

Aortopulmonary fistula

A communication between the ascending aorta and the trunk of the pulmonary artery (aortopulmonary fistula) is a rare malformation creating an L-to-R shunt similar to that observed with a patent ductus arteriosus. The size of the fistula determines the size of this shunt and the degree of volume overload for the LV. If it is very wide, the haemodynamics are the same as those of truncus arteriosus. It appears on an echocardiogram as a jet in the posterior or left lateral side of the PA trunk, which is mainly visible during diastole as it is concealed by the PA flow during systole. It is closed with a patch by sternotomy with CPB. Circulatory arrest may be necessary depending on the size of the fistula. If appropriate in view of its size, the fistula may also be occluded percutaneously (Amplatzer occlusion device).

Diastolic arterial pressure is low due to leakage into the pulmonary circuit. Intraoperatively, the recommended procedure is to hypoventilate the child in order to induce respiratory acidosis and pulmonary vasoconstriction, which reduces the shunt flow (FiO2 0.21, PaCO2 45-50 mmHg). In contrast, if the fistula has already resulted in PAH, management is aimed at reducing PVR (hyperventilation, hyperoxia).

Coronary artery anomalies

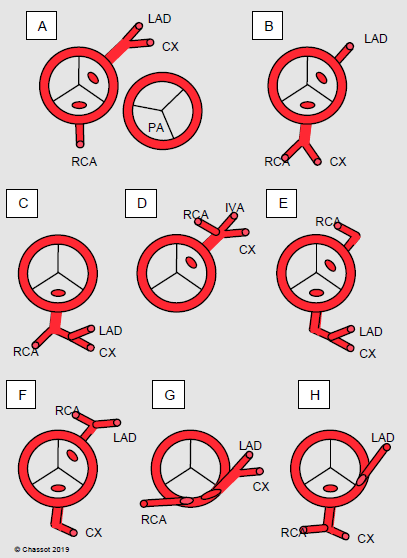

Multiple anatomical variants of coronary artery implantation exist. These anomalies may cause problem during surgical reconstruction of the outflow tracts as they cross their anterior face, blocking surgical access. A coronary artery may also originate abnormally from the aorta or be connected to the PA. In such cases, myocardial ischaemia occurs early. If the vessel is collateralised, it may divert blood from the aorta into the pulmonary system and function in the same way as a L-to-R shunt. A coronary artery may also terminate in the RV or PA, creating a left-to-right fistula with a Qp/Qs ≥ 1.5 (Figure 14.73).

The scenario that has been most extensively studied is the implantation of the left coronary artery on the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA: anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery). This normally isolated lesion is characterised by a dilated right coronary artery, which is connected to the left coronary artery by multiple collaterals located in front of the RVOT or in the interventricular septum. As soon as PVR decreases after birth, the LV myocardium becomes ischaemic as the system functions in the same way as an aortopulmonary fistula. Young children quickly become symptomatic, their ECGs show signs of ischaemia, and echocardiography reveals hypokinesis of the dilated LV and often mitral insufficiency (MI) due to ischaemia. Without surgical correction, children die in their first year. The operation involves reimplanting the trunk of the left coronary artery in the aorta if the vessel is sufficiently long. Otherwise, it is possible to perform a bypass with the subclavian or mammary artery or create a tunnel with a patch inside the PA in order to reinsert the coronary artery into the aorta.

Figure 14.73: Diagram of the most common coronary artery anomalies. A: normal situation with the position of the pulmonary valve (PA). B to H: examples of anomalies. In B, C, E, F and H, a vessel crosses the front of the PA and may cause problems during surgery of the right ventricular outflow tract. G: intramural position [3]. LAD: left anterior descending artery. CX: circonflex artery. RCA: right coronary artery. PA: pulmonary artery.

When surgery is performed, children are often in a critical condition: active ischaemia, ventricular failure, severe mitral insufficiency. The fistula effect can be reduced by increasing PVR (hypoventilation, FiO2 0.21-0.3). An opiate-based anaesthetic technique is applied (fentanyl 50-75 mcg/kg). It may take an extended time to wean the patient from CPB and this may lead to the use of a ventricular assist device. Postoperatively, inotropic support is required due to left-sided dysfunction: dobutamine, epinephrin, milrinone, levosimendan. ECMO is often necessary. Once surgery-related risks are overcome, LV function recovers usually and long-term survival is excellent [2].

Interrupted aortic arch

The aortic arch may be totally interrupted in three different sites: at the isthmus after the left subclavian artery, between the left carotid artery and the left subclavian artery, or between the brachiocephalic trunk and the left carotid artery. This is often associated with an obstruction of the LVOT. The aorta distal to the interruption is still vascularised by the patent ductus arteriosus with blood from the pulmonary circulation. Consequently, the lower part of the body and the viscera are cyanotic and the post-ductal diastolic pressure is lower than the pre-ductal pressure due to volume leakage into the pulmonary vascular bed during diastole. However, coronary perfusion is preserved.

Surgical correction must be performed within days of birth. Special cannulation is used for CPB since the aortic cannula requires two branches – one for the ascending aorta and the other for the pulmonary artery (distal aorta). The right and left pulmonary branches are temporarily clamped. The aorta is re-anastomosed and widened with prosthetic material during deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. Two arterial catheters should be used – one for the right radial artery and the other for the femoral artery [2].

|

Arterial abnormalities

|

|

Aortopulmonary fistula: L-to-R shunt and pulmonary overload. Managed in the same way as truncus arteriosus if it is large.

Coronary artery anomalies: multiple possibilities. Anomalous left coronary artery from pulmonary artery (ALCAPA): left main trunk originating from the PA. Interrupted aortic arch: the aortic arch may be totally interrupted at several locations. The distal aorta is perfused from the PA via the patent ductus arteriosus. Surgical correction within days of birth. |

© BETTEX D, BOEGLI Y, CHASSOT PG, June 2008, last update May 2018

References

- BISHOP A. Coronary artery anomalies. In: REDINGTON A, et al. ed. Congenital heart disease in adults. A practical guide. London, WB Saunders Co Ltd, 1994, pp 153-60

- NASR VG, DINARDO JA. The pediatric cardiac anesthesia handbook. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2017, 187-190

- SCHWARTZ ML, JONAS RA, COLAN SD. Anomalous origin of left coronary artery from pulmonary artery : Recovery of left ventricular function after dual coronary repair. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997 ; 30 :547-53

- SILVERSIDES CK, DORE A, POIRIER N, et al. Canadian Cardiovascular Society 2009 Consensus Conference on the management of adults with congenital heart disease: Shunt lesions. Can J Cardiol 2010; 26:e70-e79