Regardless of its initial value, systolic-diastolic ventricular function is abnormal at the end of ECC. Albeit tricky, the aim is to maintain a balance between four elements.

- Myocardial oxygen consumption;

- Heart functional capacities ;

- Cardiac output, systemic and pulmonary blood pressure;

- Body's needs.

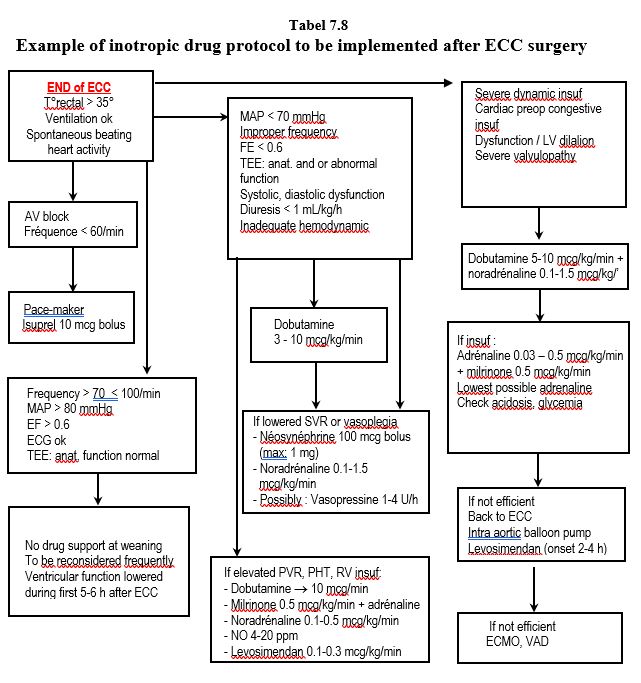

In the context of diastolic dysfunction, the heart rate should not be lower than 65 beats per minute; its value is a good marker of beta-blocker versus beta-stimulant uptake. The need for inotropic agents is constantly changing in the post-ECC period. There is no "cruising speed"; instead, needs must be constantly reassessed. Table 7.8 is a possible algorithm to guide the anaesthetist in this unstable situation. But there are almost as many different protocols as there are cardiac surgery centers! All of them are effective when properly implemented. The best routine is the one with which one is most comfortable (see Ventricular Failure ).

- Dopamine is very convenient for simple cases that need a momentary boost; it is inexpensive and its beta effect comes along with a convenient alpha stimulation to maintain RAS. Recommended maximum dose: 5 mcg/kg/min.

- The combination of dobutamine and norepinephrine allows independent measurement of alpha and beta effects. It is usually the first choice in cases of significant ventricular dysfunction.

- Adrenaline is indicated in patients with chronic ventricular failure (loss of beta receptors). It is advisable to keep the doses to a minimum (< 0.1 mcg/kg/min), and to monitor blood glucose and acid-base balance frequently.

- If LV failure persists or right-sided failure and pulmonary hypertension happen, a combination of adrenaline and milrinone is preferred.

- In refractory cases, levosimendan is indicated, but it must be started at induction to be fully effective at weaning.

- Even for a few hours, intra-aortic counterpulsation (IACP) is quick and easy to set up in the operating room and is particularly indicated after coronary revascularisation or in the presence of ventricular dilatation and mitral insufficiency. It is contraindicated in cases of aortic insufficiency and porcelain aorta (see Chapter 18 Aortic Atheromatosis).

Catecholamines must be injected via a central line (multi-lumen catheter or Swan-Ganz right atrial line); a pump drive infusion continuously flushes this line to eliminate the "dead space" effect of the tubing (flow rate 30-60 mL/hour). Cardiac failure on pump exit requires temporary assistance from the bypass machine and a very gradual stepwise weaning. During the first 20 minutes after bypass surgery, rapid temperature changes in the pulmonary artery lead to substantial underestimation of cardiac output by thermodilution [3]. Prolonged episodes of postoperative vasoplegia are related to the many mechanisms involved in a diffuse inflammatory response and endotoxemia.

The adequacy of anaesthesia is very difficult to assess if the patient is curarised; spontaneous movements are the only sure criterion for arousal in this haemodynamically unstable period. It is therefore better to curarise patients only when necessary: shivering (increased O consumption2 ), movement, spontaneous breathing, cardiogenic shock with central venous desaturation. Any movement must first command a deepening of anaesthesia. The first painful stimulation is the release of the sternal retractor; analgesia should be provided by the agent chosen for anaesthesia (fentanyl, sufentanil, etc).

The adequacy of ventilation is monitored by arterial blood gas checks. If gas exchange is impaired, some improvement measures should be taken.

- Check for bilateral ventilation (visible through the sternotomy);

- Suction secretions;

- Manually inflate the lungs with one or more vital capacity manoeuvres (20-30 second insufflations at 30-40 cm H2 O);

- Ventilate with 5-8 cm H2 O of PEEP (may cause discomfort to the operator);

- A diuretic is indicated (Lasix 5-10 mg) if water balance is very positive.

Gas checks also provide data on acid-base and fluid balance and their possible correction. Metabolic acidosis causes pulmonary hypertension and myocardial depression, both of which are deleterious at the critical time of weaning. Hyperkalaemia is common due to cardioplegia and needs to be treated in case of arrhythmias or ECG changes by administration of Ca2+ , or by insulin and glucose infusion. If it is asymptomatic, resumption of diuresis brings correction. Elevated lactate levels are common after bypass surgery and invove several causes [1].

- Low cardiac output and metabolic acidosis;

- ECC-related liver dysfunction;

- Hepato-splanchnic hypoperfusion;

- Digestive ischaemia;

- Use of Lactasol® for fluid filling.

O2 supply must correspond to needs (warming, shivering, catecholamines) and transport (cardiac dysfunction, pulmonary gas exchange). The criteria for transfusion therefore vary according to the patient's condition. Provided the patient is normovolaemic, the following recommendations can be made (see Chapter 28, Recommendations) [2,4].

- In cases of good myocardial function, complete coronary revascularisation and in the absence of severe valvular disease or bleeding, the threshold for transfusion is 70-80 g/L;

- In the elderly or debilitated, in cases of incomplete coronary revascularisation, severe valvular heart disease or ventricular failure, the transfusion threshold is between 80-90 g/L;

- In patients with low pulmonary flow (cyanotic shunt, severe PAH), the threshold is raised to 100 g/L.

The purpose of red cell transfusion is to improve tissue DO2 , not to correct Hb levels. Official recommendations specify that the indication for transfusion should not be based on Hb value, but on criteria of insufficient tissue oxygenation and haemodynamic imbalance [5].

- SaO2 < 90%;

- ScO2 decreased by > 20% (in both cerebral hemispheres) while MAP, DC and SaO2 are correct;

- SvO2 < 50%;

- O extraction coefficient2 > 50%;

- ST sub-shift, intermittent conduction block (ECG), segmental contraction abnormalities (TEE);

- Tachycardia and hypotension (most often markers of hypovolaemia; unreliable criteria for weaning);

- Metabolic acidosis, low cardiopulmonary reserves;

- In acute haemorrhage, the main criterion is haemodynamic stability; the Hb level becomes more useful in this circumstance.

The volume the perfusionist retrieves from the circuits after bypass is a perfusate containing heparin and potassium, same haematocrit as the bypass, i.e. less than 30%. It represents a good volume for fillng, but does not compensate for acute anaemia. To concentrate it, it is convenient to pass it through a washing system (CellSaver), but platelets and coagulation factors are largely lost. Modified haemofiltration (see Haemofiltration) retains these elements. In case of extension, it is recommended to repeat an antibiotic dose 6 hours after induction.

| Immediate post-ECC period |

|

This is a phase of precarious equilibrium between the body's needs and myocardial performance, which is significantly reduced by surgery, ECC, cardioplegia, hypothermia and interstitial oedema (systolic and diastolic dysfunction). With the exception of AVR for tight aortic stenosis or cure of simple ASD/VAD, the situation is more challenging for the ventricles after bypass than before. Ventricular function gradually decreases for 5 hours after ECC before normalising at around 24 hours.

The need for inotropic agents is variable and highly progressive. Therefore, a proactive attitude and early provision of inotropic support is required to avoid ventricular failure.

Monitor gas exchange, electrolytes (hyperkalaemia), blood sugar, acid-base balance.

Transfusion thresholds (except in acute haemorrhage) :

- Standard case Hb 70-80 g/L

- Dysfunction, ischemia, elderly patient Hb 80-90 g/L

- Low pulmonary output (cyanosis, PAH) Hb 100 g/L

|

© CHASSOT PG, GRONCHI F, April 2008, last update, December 2019

References

- ANDERSEN LW. Lactate elevation during and after major cardiac surgery in adults: a review of etiology, prognostic value, and management. Anesth Analg 2017; 125:743-52

- APFELBAUM JL, NUTALL GA, CONNIS RT, et al. Practice guidelines for perioperative blood management. An updatesd report of the ASA task force on perioperative blood management. Anesthesiology 2015; 122:241-75

- BAZARAL MG, PETRE J, NOVOA R. Errors in thermodilution cardiac output measurements caused by rapid pulmonary artery temperature decreases after cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesthesiology 1992; 77:31-37

- FERRARIS VA, BROWN JR, DESPOTIS GJ, et al. 2011 update to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists blood conservation clinical practice guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 91:944-82

- SPAHN DR, DETTORI N, KOCIAN R, CHASSOT PG. Transfusion in the cardiac patient. Crit Care Clin 2004; 20:269-79