Approximately 5% of patients aged > 65 years have aortic stenosis [12]. Stenotic valve disease imposes haemodynamic restrictions that do not allow cardiac output to adapt. Stroke volume becomes fixed and rate dependent: bradycardia reduces flow linearly, and tachycardia slows filling by shortening diastole (mitral stenosis) or limits ejection by shortening systole (aortic stenosis). As the flow rate is fixed, arterial pressure is closely related to peripheral resistance.

Aortic stenosis

The criteria for the severity of aortic stenosis are [2,3]:

- Tight stenosis: area < 0.6 cm /m2 , mean gradient > 40 mmHg;

- Moderate stenosis: area 0.6 - 1.0 cm /m2 , mean gradient 25 - 40 mmHg.

Moderate aortic stenosis increases the risk of surgery by a factor of three, and severe aortic stenosis by a factor of five, regardless of the patient's risk category or the number of associated risk factors [8,15]. The risk of surgery is associated with 6 different factors.

- The severity of the stenosis;

- The patient's symptoms (angina, syncope, dyspnoea, heart failure);

- The presence of associated coronary artery disease;

- The presence of severe mitral regurgitation;

- The function and size of the LV;

- The severity of the planned operation.

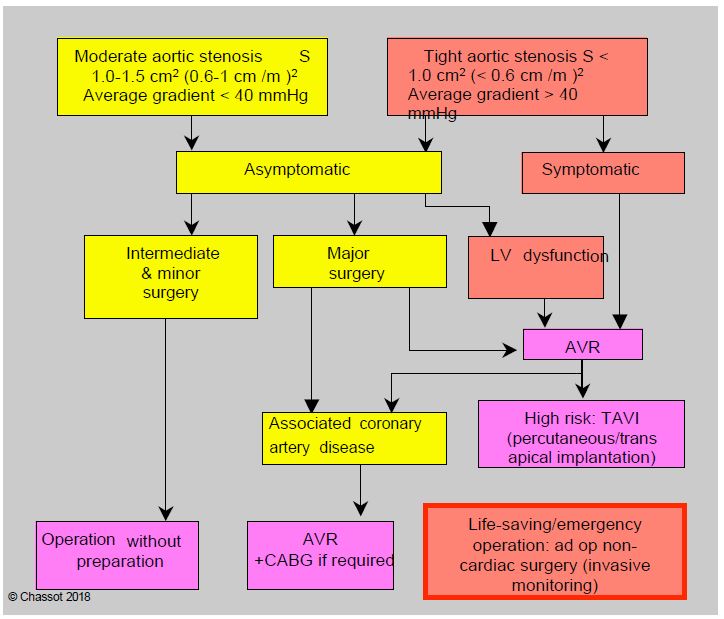

If it is symptomatic (angina, syncope and/or dyspnoea), a narrowed aortic stenosis detected in the preoperative phase of general surgery must be corrected before proceeding with any non-cardiac procedure [6,9,18]; it is preferable to use a bioprosthesis to avoid anticoagulation problems. If it is asymptomatic, there are three possible scenarios (Figure 11.31A) [4,5,18].

- The planned surgery is major (abdominal aortic surgery, liver-pancreas surgery, etc.); in this case, it is prudent to plan aortic valve replacement (AVR) before non-cardiac surgery.

- The planned operation is medium or minor: AVR is not justified; even if it is 15-25%, the cardiac morbidity is the same as in patients with mild to moderate stenosis. However, the more severe the stenosis, the greater the risk of intraoperative hypotension and the more stringent the haemodynamic control.

- The presence of LV dysfunction worsens the prognosis and strengthens the indication for preoperative AVR, but this indication is essentially based on the long-term benefit to the patient, as AVR itself has a mortality of 2% under 70 and 5% over 75 years [3].

In fact, AVR itself has its own risks and mortality (2-5%) [13]. If the expected mortality is > 5-10%, it may be advisable to replace the ECC procedure with transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) via the trans-apical or trans-femoral route (see Chapter 10, Aortic valve implantation). Balloon dilatation aortic valvuloplasty gives disappointing results in degenerative and/or calcified stenoses in older adults. In the presence of associated coronary artery disease, CABG is performed concomitantly with AVR or percutaneous angioplasty (PCI) is performed concomitantly with TAVI [3]. In addition, treating the aortic valve first significantly delays the non-cardiac procedure, which in itself may be a risk in the event of a ruptured aneurysm, invasive neoplasm or disabling orthopaedic lesion.

With advances in anaesthetic management based on rigorous haemodynamic control, recent comparative studies between patients with narrow aortic stenosis and those without stenosis tend to show that the outcomes of non-cardiac surgery without prior AVR are acceptable, even if the risk is higher [1,17]. Patients with tight stenosis have more cardiac complications (18.8% versus 10.5%), mainly related to ventricular decompensation, but 30-day mortality is little changed compared to controls: symptomatic patients 5.9% versus 3.1%, asymptomatic patients 3.3% versus 2.7% [17]. These figures are superimposed on those for high-risk and intermediate-risk surgery in the general population. In view of these good results, it is suggested that AVR be restricted to symptomatic patients. Intermediate and major non-cardiac surgery can be performed without undue risk in asymptomatic patients with narrow aortic stenosis. If the predicted mortality of AVR is greater than 5%, it may be preferable to proceed directly to non-cardiac surgery, depending on the risk, with care taken to ensure that anaesthesia is under invasive monitoring and strict haemodynamic control. TAVI (transaortic valve implantation via transapical or transfemoral catheterisation) itself carries an operative risk of 5-8% (Figure 11.31B) [13,16].

Mitral stenosis

The general approach to mitral stenosis is the same. Tight stenosis (S < 0.6 cm /m2 ) associated with pulmonary hypertension (systolic PAP > 50 mmHg) and/or clinical symptoms warrants preoperative valve replacement or percutaneous valvuloplasty. Asymptomatic tight stenosis with systolic PAP < 50 mmHg allows non-cardiac surgery, but MVR is preferred before major surgery [18].

Heart rate control is essential; in the presence of atrial fibrillation and/or massive dilatation of the LA, anticoagulation is required due to blood stagnation in the atrium and the risk of thrombus.

Valvular insufficiency

Unlike stenosis, valvular insufficiency is less restrictive: it represents volume overload and does not restrict cardiac output because the ventricles are good volume pumps. General surgery is not contraindicated for mitral (MI), aortic (AI) or tricuspid (TI) valve insufficiency, even if severe, as long as it does not lead to ventricular decompensation or clinical symptoms at rest. In symptomatic patients with ventricular dysfunction (EF < 0.30), only life-saving surgery is possible [2,18]. Hemodynamic adequacy is maintained by low afterload and positive inotropic support; bradycardia and increased SAR should be avoided. However, mortality is higher in aortic regurgitation (9%) than in mitral regurgitation (2%) [6].

The discovery of valvular regurgitation should raise two questions for the anaesthetist:

- How severe is the regurgitation? Only severe regurgitation carries significant risks, in ascending order: IT < IM < IA.

- What is the mechanism? Functional MI reflects a potentially dangerous underlying ventricular pathology, whereas organic MI (prolapse, ARF) is a stable condition.

The maximum regurgitant fraction that can be chronically supported by the LV without decompensation is 40% in MI and 30% in AI. The latter is the most dangerous form of failure because the filling pressure of the ventricle is much higher than in MI or TI, since it is the diastolic arterial pressure. In general surgery, patients with moderate to severe AI have cardiac morbidity and mortality three times higher than the standard population [10].

Prosthetic valves

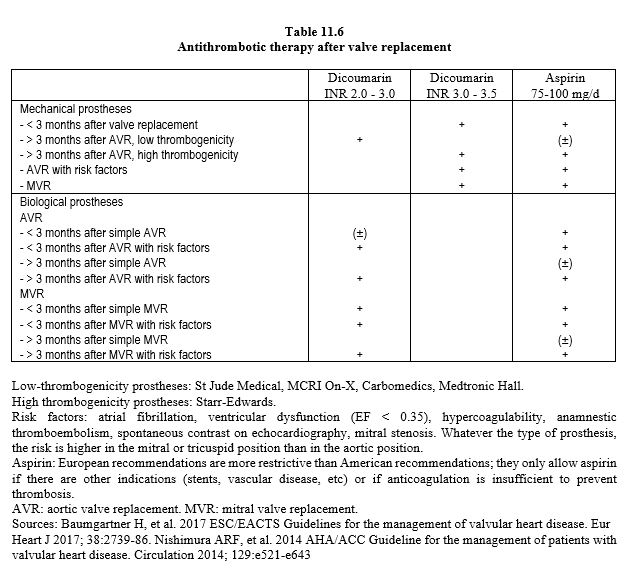

The presence of a prosthetic valve raises two issues: anticoagulation management and endocarditis prophylaxis. A mechanical prosthesis requires complete lifelong anticoagulation, whereas a biological prosthesis requires anticoagulation for only 3 months (see Table 11.6). Aspirin is continued permanently and should not be discontinued. Many operations can be carried out with the prescribed anticoagulation, but others require it to be stopped. The way in which this discontinuation is managed varies according to the prosthesis [11,14,18].

- Mechanical bicuspid aortic prosthesis, no risk factors: stop dicoumarins 48-72 hours preoperatively to allow INR to drop to 1.5 and resume as soon as possible postoperatively.

- Mechanical mitral valve prosthesis, mechanical aortic valve prosthesis with risk factors: stop dicoumarins 72 hours preoperatively, replace with an infusion of unfractionated heparin (UFH, 15,000 U/12 hours) to achieve an INR of 2.0-2.5; stop infusion 4-6 hours preoperatively and resume as soon as possible postoperatively. Low molecular weight heparins (LMWH, 100 U/kg/12 hours) in therapeutic doses may be an alternative, but current recommendations favour UFH.

- Bioprostheses: continue aspirin. During the first 3 months after implantation: as in the first case.

- No interruption of treatment for minor surgery with no risk of bleeding.

If prescribed, continue aspirin during the perioperative period. Vitamin K infusion may induce a reversal towards a very dangerous state of hypercoagulability. It is therefore preferable to use prothrombin complex or fresh frozen plasma to improve coagulation, but only in the event of bleeding. Prophylaxis against endocarditis is necessary in all patients with prosthetic devices in whom bacteraemia is likely (see Infectious endocarditis).

| Non-cardiac surgery and valvulopathy |

| Tight aortic stenosis (S < 0.6 cm /m2 ) symptomatic: preoperative AVR.

Tight asymptomatic aortic stenosis: - Major elective surgery: preoperative AVR preferable - Minor & intermediate surgery: operation without valve correction Moderate stenosis: operation without valve correction. Tight mitral stenosis (S < 0.6 cm /m2 ) symptomatic: preoperative MVR. Tight/moderate asymptomatic mitral stenosis: operation without valve correction. Severe aortic, mitral or tricuspid insufficiency: operation without valve correction, unless ventricular decompensation or symptoms at rest. Level of risk: AI > MI > TI. Moderate valve insufficiency: operation without valve correction. In patients with prosthetic valves, replace dicoumarins with a heparin infusion. Antibiotic prophylaxis is necessary in all patients with prosthetic devices where bacteremia is likely. |

References

- AGARWAL S, RAJAMANICKAM A, BAJAJ NS, et al. Impact of aortic stenosis on postoperative outcomes after noncardiac surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013; 6:193-200

- BAUMGARTNER H, FALK V, BAX JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017; 38:2739-86

- BONOW RO, BROWN AS, GILLAM LD, et al. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/EACTS/HVS/SCA/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS/ 2017 appropriate use criteria for the treatment of patients with severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70:2566-98

- CALLEJA AM, DOMMARAJU S, GADDAM R, et al. Cardiac risk in patients aged > 75 years with asymptomatic, severe aortic stenosis undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 2010; 105:1159-63

- CHRIST M, SHARKOVA Y, GELDNER G, MAISCH B. Preoperative and perioperative care for patients with suspected or established aortic stenosis facing non-cardiac surgery. Chest 2005; 128:2944-53

- FLEISHER LA, FLEISCHMANN KE, AUERBACH AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014; 130:e278-e333

- FROGEL J, GALUSCA D. Anaesthetic considerations for patients with advanced valvular heart disease undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology Clin 2010; 28:67-85

- KERTAI MD, BOUTIOUKOS M, BOERSMA M, et. Aortic stenosis: An underestimated risk factor for perioperative complications in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Am J Med 2004; 116:8-13

- KRISTENSEN SD, KNUUTI J, SARASTE A, et al. 2014 ESC/ESA Guidelines on non-cardiac surgery: cardiovascular assessment and management. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:2383-4311

- LAI HC, LAI HC, LEE WL et al. Impact of chronic advanced aortic regurgitation on the perioperative outcome of noncardiac surgery. Acta Anaesth Scand 2010;54:580-8

- NISHIMURA RA, OTTO CM, BONOW RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation 2014; 129:e521-e643

- NKOMO VT, Gardin JM, SKELTON TN, et al. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet 2006; 368:1005-11

- OSNABRUGGE RL, KAPPETEIN AP, SERRUYS PW. Non-cardiac surgery in patients with severe aortic stenosis: time to revise the guidelines? Eur Heart J 2014; 35:2346-8

- PIBAROT P, DUMESNIL JG. Prosthetic heart valves: selection of the optimal prosthesis and long-term management. Circulation 2009; 119:1034-48

- RHODE LE, POLANCZYK CA, GOLDMAN L, et al. Usefulness of transthoracic echocardiography as a tool for risk stratification of patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:505-9

- SAMARENDRA P, MANGIONE MP. Aortic stenosis and perioperative risk with noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65:295-

- TAHIRO T, PISLARU SV, BLUSTIN JM, et al. Perioperative risk of major non-cardiac surgery in patients with severe aortic stenosis: a reappraisal in contemporary pratice. Eur Heart J 2014; 35:2372-81

- VAHANIAN A, ALFIERI O, ANDREOTTI F, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). The Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2012; 33:2451-96