The ECC heat exchange capability provides excellent rewarming for hypothermic patients. The idea was first put forward by Kugelberg who brought a patient with a core temperature of 21.7°C back to normothermia [6]. In addition to homogeneous rewarming, ECC and ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) offer a support that eliminates the risk of haemodynamic collapse due to ventricular fibrillation or massive vasoplegia, and improves tissue perfusion by haemodilution. The heart is warmed before the rest of the body, and flow can be increased during the peripheral vasodilation that occurs with normothermia.

Indications

ECC is the treatment of choice for all patients whose core temperature is below 28°C, regardless of their haemodynamic status, and for those who are in circulatory collapse. Above 32°C, external (heating blanket, warm room) and internal (gastric lavage, heated infusions, peritoneal dialysis) warming is sufficient. Between 28° and 32°C, non-invasive rewarming is recommended if the heart has sinus rhythm and pressure is maintained.

Considering avalanche victims, the major problem is the combination of polytrauma and prior hypoxia. The chances of survival are better if cooling has started without suffocation, or more quickly than the onset of hypoxia. The ideal situation for the avalanche victim, for example, is to be scantily clad, shallow snowed, and have an air pocket in front of the face. If cooling is swift, O2 demand falls before suffocation and/or circulatory collapse O2 supply, then survival is good. In the case of cold water drowning, survival is impaired because of concomitant water asphyxia, unless the head has not been immersed. The presence of traumatic injuries (fractures, visceral injuries, TCC) dramatically worsens the prognosis; during rewarming, the risk of massive bleeding and crush syndrome is very high. The chances of success also vary according to circumstances. Victims of avalanches or water accidents are usually healthy sportsmen, whereas hypothermics in urban or rural areas are often homeless, alcoholics or drug addicts. However, youth no longer seems to be an advantage below 26°C.

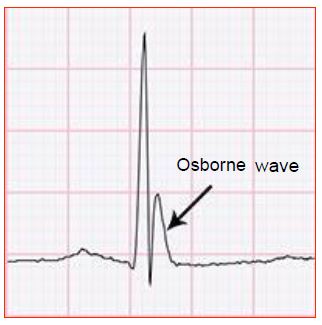

Livid, hypertonic, pulseless, mydriatic and apnoeic, a cold patient is not a dead patient, but looks like one! Outside the hospital, if the airways are clear, cardiopulmonary resuscitation is carried out according to the usual recommendations, with endotracheal intubation, cardiac massage in case of asystole, and defibrillation in case of ventricular fibrillation. When the rhythm is still sinus or nodal, the ECG usually shows an Osborne wave, which is a positive deflection starting at the end of the QRS, present in almost all leads, and whose amplitude is proportional to the depth of hypothermia (Figure 7.58) [8].

Figure 7.58: ECG of a hypothermic patient with an Osborne wave.

Depolarising curares (succinylcholine) are contraindicated because of the risk of hyperkalaemia. The hypothermic heart responds poorly to pharmacological agents, whose circulation and metabolism are dramatically slowed; it is wise to use adrenaline only when the temperature is > 30°C. In ventricular fibrillation, it is recommended that no more than 3 attempts at defibrillation (maximum power) should be made, but to wait until 30°C for further shocks [10]. AF is common when the core temperature is < 32°C; ventricular fibrillation usually occurs < 28°C.

Core temperature is measured in the lower third of the oesophagus. Tympanic temperature is not reliable because it is influenced by the temperature of the external auditory canal; infrared thermometers are ineffective in hypothermia, as is pulsoxymetry [3]. Death is only declared if the airway is obstructed (obvious asphyxia) and the patient is in asystole, or if major traumatic injuries account for death [3,10]. Outside of these circumstances, an hypothermic patient cannot be declared dead until he or she is rewarmed to > 32°C [3].

According to the Swiss recommendations for the management of mountain accidents, hypothermia is classified into 4 stages [4].

- Stage I: 32-35°C, patient conscious and shivering;

- Stage II: 28-32°C, altered consciousness, no shivering;

- Stage III: 24-28°C, patient unconscious, but vital signs present;

- Stage IV : < 24°C, no vital signs.

Rewarming ECC is clearly indicated in stage IV, and in stage III if haemodynamics are unstable or non-invasive rewarming is ineffective. Logistic regression was used to identify three criteria that are independently associated with survival [3,9]:

- Kalemia < 12 mmol/L ;

- PaCO2 < 80 mmHg;

- No severe trauma.

Above these values, the chances of survival are zero because irreversible damage has occurred before the patient is cooled. Below these values or in their absence, active resuscitation is required, remembering that "No one is dead until warm and dead". However, these criteria do not seem to apply to children; indeed, in a series of 12 children aged 2-12 years rewarmed on bypass after drowning in cold water and body temperature below 25°C, neither pH, potassium nor PaCO2 were found to be discriminating factors between survivors and non-survivors. In adults, potassium > 12 mmol/L was the determining criterion for irreversible damage. No patient survived rewarming to this level of hyperkalaemia, whereas those with a central T° lowered to 14°C showed no neurological sequelae after resuscitation [2].

In avalanche victims, it is not clear whether asphyxia preceded hypothermia, or whether hypothermia protected the body during circulatory collapse and ventricular arrest or fibrillation. In this case, the following criteria reduce the chances of survival to zero [1,3,7,10].

- Burial for > 35 minutes under snow with airway obstruction;

- Cardiac arrest and airway obstruction (choking);

- Potassium > 12 mmol/L.

Technique

Currently, ECMO (see Chapter 12 Short-term devices) is preferred to standard resuscitation because results are significantly better, especially because ARDS, which occurs very frequently after resuscitation, is better managed by ECMO in the following hours [2]. Femoral artery and vein cannulation allows rapid initiation of ECMO without interfering with resuscitation measures (ECM, intubation, etc); it provides a flow rate of 5 L/minute in adults, which allows a temperature rise of 1°C per 5 minutes. The temperature gradient between the patient's blood and the heat exchanger should not exceed 10°C. Blood temperature should never be higher than 37°C. The use of heparinised circuits reduces the dose of systemic heparin and thus secondary bleeding. In children, the femoral vessels are often too thin to allow a satisfactory flow; a sternotomy is then necessary to perform a conventional cannulation.

Usually, heart rate resumes between 25° and 30°C, but often fibrillates; this fibrillation is usually refractory to electric shocks below 30°C. If no cardiac activity has resumed by 32°C, the arrest is permanent [2]. Patients show signs of waking up when the core temperature exceeds 32°C. The vasodilation that occurs with rewarming consumes large amounts of crystalloids and usually requires an infusion of noradrenaline. Alterations in coagulation factors and platelet adhesiveness in the cold make haemostasis difficult and require infusions of coagulation factors and platelets. Postoperatively, ARDS (42%), pneumonia (22%) and renal failure (20%) are common [11].

Results

The literature consists mainly of single case reports. The few published series give a success rate without neurological sequelae of 50-60% [2,9,11,12].

A Swiss study reported a survival rate of 47% (15 patients discharged alive from hospital out of 32 hypothermic accident victims with a mean temperature of 21.8°C); neurological status was normal in 14 patients, with only one showing a slight disability [12]. The causes of hypothermia were avalanche, fall into a crevasse, immersion in cold water or suicide. All were in circulatory arrest and in fixed mydriasis on arrival. The average time from discovery to bypass was 141 minutes, and the bypass time was 98 minutes.

A Finnish group published a study of 75 hypothermic patients, 42 of whom could be rewarmed by non-invasive means because they were haemodynamically stable [9]. Out of the 25 collapsed patients, only one had severe CCT and one had prior asphyxia; the others suffered from exposure to cold air or cold water immersion. These 23 patients, who arrived at the hospital with cardiac massage, had a mean temperature of 24°C and were massaged for 106 minutes before the start of the bypass procedure, which lasted on average 137 minutes. Fourteen (61%) were discharged alive. In a Polish series of 25 patients rewarmed by ECC (out of 152 cases of severe accidental hypothermia), fifteen (60%) survived without sequelae [5].

There is no correlation between long-term survival and time from accident to rewarming or temperature on arrival provided it is above 12°C. As the functional recovery of survivors is excellent, there is much reason to be aggressive in the management of deep hypothermia.

| Rewarming ECC |

|

Indications: accidental hypothermia with central T° < 28°C and hemodynamic instability or circulatory arrest. Survival without neurological sequelae in 55% of cases. Conditions for success:

- Chilling without prior asphyxia or major trauma

- Kalemia < 12 mmol/L

- PaCO2 < 80 mmHg

Arteriovenous femoral bypass or ECMO technique

- Reheat by 1°C per 5 minutes

- Maximum gradient between blood and heat exchanger temperature: 10°C

- Blood temperature never > 37°C

As the functional recovery of survivors is excellent, there is every reason to be aggressive in the management of deep hypothermia patients, who cannot be known to have died until they have been rewarmed

|

© CHASSOT PG, GRONCHI F, April 2008, last update, December 2019

References

- BOYD J, BRUGGER H, SHUSTER M. Prognostic factors in avalanche resuscitation: a systematic review. Resuscitation 2010; 81:645-52

- BROWN DJA, BRUGGER H, BOYD J, et al. Accidental hypothermia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:1930-8

- BRUGGER H, DURRER B, ELSENSOHN F, et al. Resuscitation of avalanche victims: evidence-based guidelines of the International commission for mountain emergency medicine (ICAR MEDCOM) intended for physicians and other advanced life support personnel. Resuscitation 2013; 84:539-46

- DURRER B, BRUGGER H, SYME D. The medical on-site treatment oh hypothermia. ICAR-MEDCOM recommendation. High Alt Med Biol 2003; 4:99-103

- JAROSZ A, KOSINSKI S, DAROCHA T, et al. Problems and pitfalls of qualification for extracorporeal rewarming in severe accidental hypothermia. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2016; 30:1693-7

- KUGELBERG J, SCHULLER H, BERG B, et al. Treatment of accidental hypothermia. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1967; 1:142-6

- LAVONAS EJ, DRENNAN IR, GABRIELLI A, et al. 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 10: special circumstances of resuscitation. Circulation 2015; 132:S501-18

- SHINDE R, SHINDE S, MAKHALE C, et al. Occurrence of "J waves" in 12-lead ECG as a marker of acute ischemia and their cellular basis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2007; 30:817-9

- SILVFAS T, PETTILÄ V. Outcome from severe accidental hypothermia in Southern Finland - A 10-year experience. Resuscitation 2003; 59:285-90

- SOAR J, PERKINS GD, ABBAS G, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010. Section 8. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances: Electrolyte abnormalities, poisoning, drowning, accidental hypothermia, hyperthermia, asthma, anaphylaxis, cardiac surgery, trauma, pregnancy, electrocution. Resuscitation 2010; 81:1400-33

- VRETENAR DF, URSCHEL JD, PARROTT JC, UNRUH HW. Cardiopulmonary bypass resuscitation for accidental hypothermia. Ann Thorac Surg 1994; 58:895-8

- WALPOTH BH, WALPOTH-ASLAN BN, MATTLE HP, FISCHER A, VON SEGESSER L, et al. Outcome of survivors of accidental deep hypothermia and circulatory arrest treated with extracorporeal blood warming. N Engl J Med 1997; 337:1500-5