Patient-prosthesis mismatch

The useful surface area of the prosthesis is too small for the size of the patient if it is < 0.85 cm2 /m2 at the aortic level or < 1.2 cm2 /m2 at the mitral level. This patient-prosthesis mismatch (PPM) results in an excessive transvalvular gradient and is detrimental to patient outcome. When severe, it leads to persistent ventricular remodelling or pulmonary hypertension, worsening of long-term ventricular dysfunction and an increase in 5-year mortality of up to 15-25% [2,24]. The discordance may be [22]:

- Moderate: aortic S 0.65 -0.85 cm2 /m2 , mitral S 0.9 - 1.2 cm2 /m2 ;

- Severe: aortic S < 0.65 cm2 /m2 , mitral S < 0.9 cm2 /m2 .

The incidence of severe patient-prosthesis mismatch is 9-12% and moderate mismatch is 30-50% [3,13]. Its clinical impact is significant in young people with high cardiac output, but less pronounced in those aged >70 years [7]. A disproportionate increase in gradient on exercise testing (> 20 mmHg for aortic prosthesis and > 12 mmHg for mitral prosthesis) indicates significant stenosis [23]. While the severe form is associated with a significant impact on quality of life and mortality, the impact of a modest mismatch is controversial as it is not significant in the presence of normal ventricular function.

The surface area of a prosthesis should therefore be > 0.85 cm2 /m2 in the aortic position and > 1.2 cm2 /m2 in the mitral position. When choosing a valve size, it is important to consider the effective surface area calculated on echo (see Tables 11.8 and 11.9) and not the nominal surface area provided by the manufacturer, which varies according to the method of calculation [22]. In addition, haemodynamic performance varies between models: it is superior for mechanical valves compared with mounted bioprostheses, for not mounted bioprostheses compared with mounted bioprostheses, and for supra-annular prostheses compared with intra-annular prostheses. TEE measurement of the size of the aortic annulus prior to ECC is critical in determining the size of the prosthesis and in deciding which model to choose or whether to enlarge the aortic annulus to avoid implanting a valve that is too small. Calculating the minimum prosthesis size is straightforward:

- In aortic position: body S x 0.85 cm2 ; S for a normal adult: > 1.5 cm2;

- In mitral position: body S x 1.2 cm2 ; S for a normal adult: > 2.0 cm2

Correct fitting is particularly important in people aged < 65 years, in those who are very active and in those with a long life expectancy. A significant patient-prosthesis mismatch in an elderly patient is unlikely to justify a return to ECC to attempt placement of a larger valve.

Prosthesis leaks

To prevent inadvertent blockage and to ensure self-washing, winglet and disc valves are deliberately not tight and always have several small regurgitant jets, the configuration of which is specific to each model, but which are always located within the ring. They represent less than or equal to 5% of regurgitation and are not haemodynamically significant (see Figure 11.43). Bioprostheses present a leak of variable configuration, generally central and very modest. Stentless prostheses, which are flexible and more delicate to insert, can have significant leaks if implantation is not perfect.

Video: Normal washing leaks from a St-Jude prosthesis in the mitral position; the colour flow that appears upstream of the prosthesis represents the displacement of blood associated with the closure of the fins.

Leaflets valves have a certain inertia to occlusion and when they close they push back the blood mass within their annulus. This reflux may be visible on colour Doppler echocardiography (closure reflux), but does not constitute a leak as such.

The aortic and mitral valves are placed side by side on the fibrous trine. As a result, the attachment points of an aortic or mitral prosthesis can pull on the opposite valve and cause new insufficiency or worsen existing regurgitation. In the mitral valve, this insufficiency is due to retraction of the anterior leaflet or a tear at the leaflet base; in the aortic valve, it is secondary to retraction of the left aortic and/or non-coronary cusps.

Video: Major posterior pravalvular leak after mitral valve replacement.

Video: Major inferior paravalvular leak after MVR with a St-Jude prosthesis.

Video: Para-annular leakage orifice following mitral plasty in three-dimensional reconstruction (view from the LA); it is located opposite the tricuspid valve.

Video: Major anterior paravalvular leak after MVR with a bioprosthesis.

Video: Paravalvular leaks after aortic valve replacement; the short-axis view shows two leak ports at 3 o'clock and 6 o'clock, opposite the left and right coronary cusps, respectively.

Video: Major paravalvular leak after aortic valve replacement in long-axis view; the leak is located at the mitro-aortic angle, where the prosthesis no longer has contact with the wall.

- The average rate of paravalvular leakage is 12% [30]. Minor leaks are common (6-18% after AVR, 22-32% after MVR) but not significant [16]; in the aortic region, they disappear rapidly with protamine or within a few days with fibrin deposition and endothelialisation. In the mitral region, half of them persist for a year, with no effect on mortality or cardiovascular complications [30].

- Small leaks are inevitable when the valve annulus is heavily calcified and congruence with the prosthetic annulus is impossible.

- In the tricuspid region, the surgeon sometimes does not fix the prosthesis on the septal side to avoid damaging the His bundle, leaving an extra-annular orifice.

- Moderate to severe leaks (1-2% of cases) show a clearly visible zone of convergence (PISA) on the upstream side of the valve and a significant vena contracta. On 3D echocardiography, they are manifested by a paravalvular orifice representing > 10% of the valve circumference. They must be corrected immediately if possible, as they tend to get worse over time (dehiscence); sometimes the technical conditions for prosthesis implantation are such that any attempt to improve them is doomed to failure. Surgical correction of leaks fails in 10-20% of cases [9].

- Aortic leaks are more tolerable than mitral leaks because the velocity is lower and there is less risk of haemolysis. Tolerance is very high for tricuspid PVLs, which have a low velocity.

- Operative indications for chronic PVL are: regurgitation leading to clinical symptoms and/or ventricular decompensation, endocarditis, haemolysis (LDH > 600 U/mL) with anaemia requiring repeated transfusions [22].

Immediately after prosthesis placement, the decision to return to bypass to close the paravalvular orifice is not based solely on the TEE image, but on a series of contingencies: incriminated valve, condition of the annulus, surgical feasibility of repair, clinical risk of 2nd ECC, etc. If surgery is too risky, it is possible to reduce a paravalvular leak with an occluder device used to close AICs (Amplatzer™ type occluder) (see Figure 11.47B). The success rate varies from 60% to 90% of cases; the leak is often reduced but not eliminated; the effect on haemolysis is inconsistent [8].

Dynamic obstruction of the LVOT ("HOCM effect")

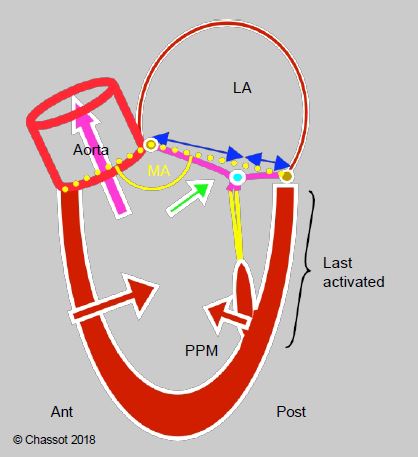

In the context of valve surgery, dynamic obstruction of the LVOT, or the obstructive cardiomyopathy effect (HOCM effect), occurs mainly on exiting bypass in three different situations: after mitral valve surgery, after MVR with a bioprosthesis, and after aortic replacement for stenosis. Normally, the point of coaptation between the two leaflets of the mitral valve is held posteriorly away from the outflow tract by several elements (Figure 13.9) [17,18].

- The mitral valve angle is open enough to separate the inflow tract from the outflow tract; diastolic filling flow and systolic ejection flow are almost parallel.

- The anterior mitral leaflet is longer than the posterior leaflet.

- The radial inward displacement of the posterior wall is less than that of the anterior and lateral walls.

- The posterobasal wall is electrically activated last.

- Intraventricular pressure seals the mitral valve by compressing the two leaflets.

Figure 13.9: Diagram showing the normal relationship between the mitral valve and the LV outflow tract. The mitral valve angle (MA, in yellow) is open (> 150°). The coaptation point of the mitral valve is located at the posterior quarter of the valve diameter (blue arrows). The posterior wall has less travel than the anterior wall and is activated last. Intraventricular pressure maintains mitral valve closure by pushing the two leaflets together (green arrow). The system is designed to keep the mitral coaptation point as far away as possible from the LVOT in systole.

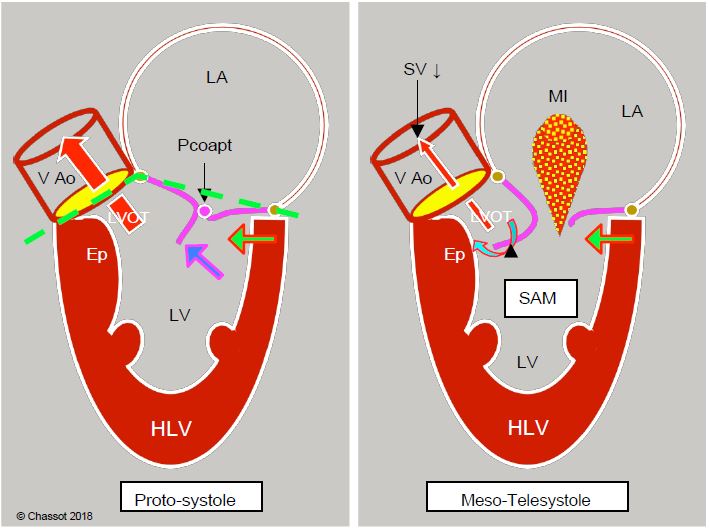

Several structural phenomena contribute to the anterior displacement of the coaptation point of the mitral valve (Figure 13.10) [10].

- In concentric hypertrophy of the LV (aortic stenosis), the ventricular cavity decreases in size and the posterior wall moves closer to the outflow tract because the anterior junction between the aorta and the mitral valve is a fixed point anchored to the trine, which forms the fibrous skeleton connecting the mitral, aortic and tricuspid valves. Only the posterolateral part can move inwards as the LV narrows.

- The mitral valve angle is narrowed by septal hypertrophy and anterior displacement of the posterior wall.

- LV function is good (EF > 60%). Excessive stimulation β increases the radial systolic stroke of the posterior wall, which is too far anterior.

- Hypovolaemia and vasoplegia reduce ventricular volume to the point where the antero-posterior diameter is excessively reduced during systole. The same process occurs after AVR: the removal of the obstacle to ejection represented by a narrow aortic stenosis causes a sudden drop in LV afterload, leading to true ventricular collapse in telesystole.

- Excess tissue in the posterior mitral leaflet alters the length ratio between the two leaflets and shifts the coaptation point anteriorly towards the LVOT; this typically occurs in Barlow's disease. After mitral valve repair, inadequate resection of the posterior leaflet and/or an overly restrictive annulus will also shift the coaptation point anteriorly.

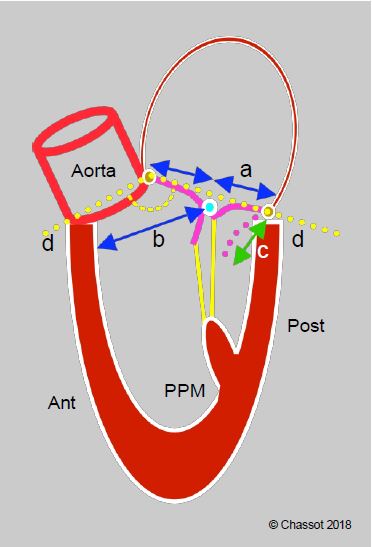

- A number of preoperative factors are risk markers for anterior displacement of the coaptation point and tilting of the anterior leaflet into the LVOT (systolic anterior motion, SAM) (Figure 11.49) [20,27].

- EF > 60% and reduced left ventricular cavity size;

- Posterior leaflet height > 15 mm;

- Reduced aorto-mitral angle (< 140°);

- Distance between interventricular septum and mitral coaptation point (C-sept) reduced (< 2.5 cm);

- Anterior displacement of the anterolateral papillary muscle.

Figure 13.10: Dynamic subaortic stenosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Concentric hypertrophy and ventricular cavity narrowing (often exacerbated by hypovolaemia, reduced afterload or beta inotropic over-stimulation) displace the posterobasal portion of the LV anteriorly (green arrow). In the protozoan, the anterior leaflet and the coaptation point (Pcoapt) of the mitral valve are displaced towards the outflow tract (LVOT) and the angle between the plane of the aortic valve and that of the mitral valve closes (mitro-aortic angle: green dotted line). The coaptation point is located between the edge of the posterior leaflet and the body of the anterior leaflet, with the distal part of the anterior leaflet floating within the LV (blue arrow). At the start of systole, intraventricular pressure pushes the anterior leaflet into the LVOT instead of against the posterior leaflet. The acceleration of the flow in the LVOT then creates a Venturi effect, which secondarily sucks in the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve (SAM). In mesotelesystole, the mitral leaflet contributes to the dynamic obstruction of the LVOT. As the mitral valve is no longer occluded, mitral regurgitation (MI) occurs in the second half of systole. Ep: hypertrophied septal spur. LVH: Left ventricular hypertrophy. SAM: systolic anterior motion. VAo: aortic valve.

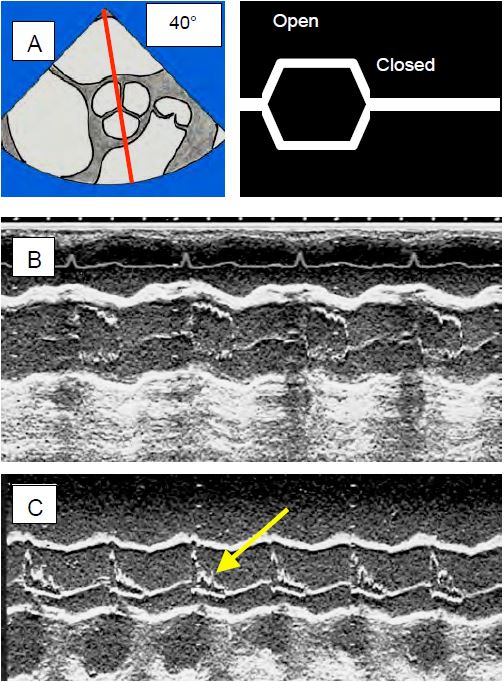

Coaptation no longer takes place via the free edges of the two leaflets; the tip of the posterior leaflet comes into contact with the body of the anterior leaflet, leaving its distal part floating in the ventricular cavity. These phenomena bring the mitral coaptation point closer to the plenum during systole. Intraventricular pressure then pushes the anterior leaflet into the LVOT rather than against the posterior leaflet. As this happens during systole, the flow is already accelerated in the outflow tract and the anterior leaflet can then be sucked in by the Venturi effect. As a result, it more or less completely occludes the LVOT. This is the SAM (systolic anterior motion) that occurs during meso-tesystole. The maximum velocity reached in the LVOT is > 2.5 m/s; the gradient is > 30 mmHg at rest and > 50 mmHg during exercise [10,15]. Mesosystemic narrowing of the LVOT causes a decrease in stroke volume, resulting in partial collapse of the aortic valve leaflets during systole (Figure 13.13).

Video: Anterior displacement of the anterior mitral leaflet (AML) in the left outflow tract; the leak induced by the mesosystolic reopening of the mitral valve is significant but short-lived.

Video: Anterior displacement in the left outflow tractr of the anterior mitral leaflet (SAM); the leak induced by the mesosystolic reopening of the mitral valve lasts only half of systole.

Figure 11.49: Predictors of anterior leaflet tilt in postoperative SAM. a: ratio of anterior leaflet height to posterior leaflet height < 1.3. b: distance between coaptation point and septum < 2.6 cm. c: height of posterior leaflet distended in diastole > 1.5 cm. d: closed mitral valve angle (< 140°) [20].

The SAM phenomenon occurs at the end of ECC in 14% of AVR for stenosis [1]. In this situation, it is essential to calculate the transvalvular gradient using Bernoulli's equation, which takes into account the velocity in the outflow tract: ΔP = 4 · (Vtotal2 - VLVOT2 ), because the latter (VLVOT ) is well above 1.5 m/s; it alone gives a ΔPmax > 25 mmHg, which must be subtracted from the total gradient of the ejection tract (Vtotal) to measure the gradient specific to the prosthesis. The ratio between the velocity in the LVOT and that across the valve (VLVOT / VVAo ) is useful in assessing the degree of acceleration generated by the prosthesis; normally this ratio should be > 0.4 [32].

After mitral replacement with an attached bioprosthesis, we may encounter a HOCM effect induced by one of the 3 tips of the prosthesis, which partially obstructs the LVOT. After mitral repair, the mitral coaptation zone approaches the LVOT because the fixed point of the mitral annulus is at the level of the mitral-aortic junction (fibrous trine), whereas the posterior part is thin and supported only by the ventricular musculature; this part will therefore move anteriorly (see Figure 11.57). Excessive anterior displacement (SAM) occurs in 4-11% of mitral valve repair cases [28]. There are four possible causes [19].

Video: Displacement of the anterior mitral leaflet in the LV outflow tract (SAM) in a case of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (long-axis view).

- The valvuloplasty ring is too restrictive; SAM is more common after a complete restrictive rigid ring than after a semi-rigid open ring.

- The length of the posterior leaflet is excessive (excess tissue).

- The ventricular cavity is too small: hypovolaemia, concentric LVH.

- The radial displacement of the posterior wall during systole is too great: over-stimulation β, vasoplegia.

Figure 13.13: Echocardiographic views of the aortic valve in TM (time motion) mode. The decrease in stroke volume (SV) leads to the collapse of the aortic valve leaflets because the SV collapse can no longer keep the valve open. A: TM axis through a short-axis view of the aortic valve, showing the opening and closing of the aortic valve. B: The normal image is almost square, the valve is open throughout systole. C: The image in HOCM shows collapse of the leaflets (arrow) in mesosystole. This appearance is pathognomonic for subocclusion of the LVOT.

The first two are related to the surgical procedure and occur in 7% of mitral valve repair cases [11,28]. They are related to haemodynamics and can be corrected by treating the dynamic obstruction of the LVOT [28]:

- Increase in preload (filling);

- Increase in afterload by vasoconstrictors (neosynephrine, noradrenaline);

- Decreased contractility (withdrawal of catecholamines, β-blocking with esmolol);

- Re-operation: rarely necessary (6-8% of cases).

The result of the "HOCM effect" is a low cardiac output characterised by severe systemic hypotension and cardiogenic shock refractory to catecholamines, but with preserved or even increased filling pressures. The diagnosis can only be made by echocardiography. The only treatment is to stop catecholamines β, refill the arteries and increase systemic arterial resistance (vasoconstrictor α ); in refractory cases, β blockade is necessary.

Anticoagulation

The anticoagulation required for the first 3 months with bioprostheses and for life with mechanical valves is a major source of haemorrhagic complications. As the risk of thrombogenesis is greater in the mitral position than in the aortic position, we aim for an INR of 3.0-3.5 for MVRs and 2.0-3.0 for AVRs, with the addition of aspirin (75-250 mg/d) in the absence of contraindications (Table 11.6). Anti-vitamin K (AVK) agents are the only appropriate anticoagulants for prosthetic valves; if treatment is interrupted in the event of surgery, heparin (UFH or LMWH) must be substituted (see Valvulopathies and Noncardiac Surgery). The new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban) have not been shown to provide effective protection against thromboembolic events in rheumatic mitral stenosis, mitral valve prosthesis, mechanical valve prosthesis or bioprosthesis; these four situations remain within the scope of the AVKs [6]. On the other hand, NACOs can be used in AF for native valve disease such as aortic stenosis, mitral regurgitation or aortic regurgitation, but not for mitral stenosis, where AVKs are still recommended [5,14]. Given the risk of bleeding, the optimal anticoagulation regimen for mechanical prostheses remains uncertain, and the benefit of adding antiplatelet agents has not been proven, except in polyvascular patients [21].

Other complications

In the long term, mechanical prostheses carry a significant risk of thrombosis and thromboembolism and require lifelong anticoagulation, which is itself a source of haemorrhagic complications. Bioprostheses do not require anticoagulation, but their lifespan is limited by progressive degeneration and calcification. A number of complications are common to the different valve types [12,22,26,29].

- Thromboembolism: incidence 1-2% patient/year; thrombosis occurs mainly with mechanical prostheses in the setting of ineffective anticoagulation, more often in the mitral position than in the aortic position. Associated risk factors are atrial fibrillation, dilatation of the LA, left-sided dysfunction and a hypercoagulable state [22]. If improved anticoagulation (increase in INR, addition of aspirin) is not sufficient to resolve the thromboembolic problem, or if the thrombus is large (≥ 10 mm) and mobile, surgical removal is necessary; if this is too risky (4-15% mortality), rescue thrombolysis may be considered. In the right heart, thrombolysis is preferred.

- Bleeding: The risk of major bleeding in anticoagulated patients is 1% patient/year.

- Occlusion: The incidence is 0.3-1.3%/patient/year with mechanical prostheses [25]. The development of fibrous pannus can occur with any type of prosthesis; it limits the movement of the blades or cusps and can completely block the prosthesis [4]. Whether thrombus or pannus, surgery is indicated if the stenosing effect is severe or if the mass is large (> 5-10 mm) and floating (mortality 4-20% depending on clinical condition). Thrombolysis is a possible option if the surgical risk is too high.

- Structural degradation: the rate of degradation of bioprostheses is 15-30% after 10 years and 20-50% after 15 years, depending on the model; accelerating factors are young age (< 40 years), mitral position, renal insufficiency and hyperparathyroidism. Treatment of the tissue with gluaraldehyde favours subsequent calcification, but part of the phenomenon is related to active processes such as atheromatosis and immune reactions (the tissue is not completely inert).

- Endocarditis: incidence 0.5% patient/year despite adequate prophylaxis, mortality 30-50%. Surgery is indicated in cases of medical failure, severe regurgitation, vegetation > 10 mm, fistula or progressive ventricular failure.

- Paravalvular leak: Severe leaks are rare (1-2%); surgical correction is required if symptomatic and/or leading to ventricular failure or significant haemolysis.

- Haemolysis: the majority of patients with mechanical prostheses have a low level of haemolysis, but only those who become anaemic require treatment for the cause, most commonly a paravalvular leak. Haemolysis is caused by the collision, shearing and fragmentation of a regurgitant jet with a rigid foreign surface such as the valve annulus [31].

- Mechanical accidents (breakage, loss of winglet) are extremely rare.

Video: Blockage of a fin in a case of St-Jude prosthesis in mitral position.

If there is any doubt about the function of a prosthetic valve, cineangiography is the only way to visualise the movement of the winglets with certainty.

| Complications of heart valve prostheses |

| Patient-prosthesis mismatch: The effective surface area of the prosthesis is too small for the patient's cardiac output if it is < 0.85 cm2 /m2 at the aortic level or < 1.2 cm2 /m2 at the mitral level.

The prostheses are not completely tight and may leak slightly. The mechanical valves maintain minimal regurgitation when closed to prevent fibrin and thrombus deposition (washing leak). All of these leaks are located within the prosthetic ring.

Paravalvular leaks are outside this ring and are always pathological. If they are small, they can be ignored; most disappear spontaneously. When they are large, they require immediate return to ECC or subsequent reoperation if repair is feasible and the risk is not too high. Indications for surgery: large leak, ventricular failure, haemolysis, endocarditis.

Dynamic obstruction of the LVOT by forward displacement of the anterior mitral leaflet is common in certain circumstances:

- Aortic stenosis obstruction

- Too restrictive mitral regurgitation

- Reduced LV chamber (hypovolaemia, severe concentric LVH)

- Reduced afterload (AVR in stenosis, vasoplegia, IABP)

- Excessive catecholamine stimulation β

The average complication rate for prostheses is 3% per year. The most common complications of valve replacement are

- Thromboembolism (0.6 - 2.3% patient/year)

- Bleeding due to anticoagulation (1% patient/year)

- Structural degradation of bioprostheses (10-30% at 10 years and 20-50% at 15 years)

- Endocarditis (0.5% patient/year)

- Paravalvular leak (1-2%)

- Haemolysis

|

References

- BARTUNEK J, SYS SU, RODRIGUEZ AC, et al. Abnormal systolic intraventricular flow velocities after valve replacement for aortic stenosis. Circulation 1996; 93:712-9

- BLAIS C, DUMESNIL JG, BAILLOT R, et al. Impact of valve prosthesis-patient mismatch on short-term mortality after aortic valve replacement. Circulation 2003; 108:983-8

- BLEIZIFFER S, EICHINGER WB, HETTICH I, et al. Impact of patient-prosthesis mismatch on exercise capacity in patients after bioprostheic aortic valve replacement. Heart 2008; 94:637-41

- CANNEGIETER SC, TORN M, ROSENDAAL FR. Oral anticoagulant treatment in patients with mechanical heart valves: How to reduce the risk of thromboembolic and bleeding complications. J Intern Med 1999; 245:369-74

- DOHERTY JU, GLUCKMAN TJ, HUCKER WJ, et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway for periprocedural management of anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69:871-98

- EIKELBOOM JW, CONNOLLY SJ, BRUECKMANN M, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves, N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1206-14

- FEINDEL CM. Counterpoint: aortic valve replacement: size does matter. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009; 137:284-5

- GARCIA-FERNANDEZ MA,CORTES M, GARCIA-ROBLES JA, et al. Usefulness of transesophageal echocardiography in evaluating the success of percutaneous transcatheter closure of mitral paravalvukar leaks. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010; 23:26-32

- GENONI M, FRANZEN D, VOGT P, et al. Paravalvular leakage after mitral valve replacement: Improved long-term survival with aggressive surgery? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000; 17:14-9

- GERSH BJ, MARON BJ, BONOW RO, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Executive summary. Circulation 2011; 124:2761-96

- GILLINOV AM, COSGROVE DM, LYTLE BW, et al. Reoperation for failure of mitral valve repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1997; 113:467-73

- HAMMERMEISTER KE, SEHTI GK, HENDERSON WG, et al. Outcomes 15 years after valve replacement with a mechanical versus bioprosthetic valve: final report of the Veterans Affairs randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36:1152-8

- HEAD SJ, MOKHLES MM, OSNABRUGGE RI, et al. The impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch on long-term survival after aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 34 observational studies comprising 27'186 patients with 133'141 patient-years. Eur Heart J 2012; 33:158-29

- HEIDBUCHEL H, VERHAMME P, ALINGS M, et al. European Heart Rythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Europace 2015; 17:1467-507

- HENSLEY N, DIETRICH J, NYHAN D, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a review. Anesth Analg 2015; 120:554-69

- IONESCU A, FRASER AG, BUTCHART EG, et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of incidental paraprosthetic valvular regurgitation: A prospective study using transesophageal echocardiography. Heart 2003; 89:1316-21

- JAIN P, PATEL PA, FABBRO M. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: expecting the unexpected. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2018; 32:467-77

- LEFEBVRE XP, HE S, LEVINE RA, et al. Systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve in hypertrophic cardoimyopathy: an in vitro pulsatile flow study. J Heart Valve Dis 1995; 4:422-38

- LOULMET DF, YAFFEE DW, URSOMANNO PA, et al. Systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve: a 30-year perspective. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 148:2787-94

- MASLOW AD, HAERING JM, LEVINE RA, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve after mitral valve reconstruction for myxomatous valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999; 34:2096-104

- MACISAAC S, JAFFER IH, BELLEY-CÔTÉ EP, et al. How did we get here? A historical review and critical analysis of anticoagulation therapy following mechanical valve replacement. Circulation 2019; 140:1933-42

- PIBAROT P, DUMESNIL JG. Prosthetic heart valves: selection of the optimal prosthesis and long-term management. Circulation 2009; 119:1034-48

- PICANO E, PIBAROT P, LANCELLOTTI P, et al. The emerging role of exercise testing and stress echocardiography in valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54:2251-60

- RAHIMTOOLA SH. Choice of prosthetic heart valve in adults. An update. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55:2413-26

- ROUDAUT R, SERRI K, LAFITTE S. Thrombosis of prosthetic heart valves: diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Heart 2007; 93:137-42

- RUEL M, KULIK A, RUBENS FD, et al. Late incidence and determinants of reoperation in patients with prosthetic heart valves. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004; 25:364-70

- TAVLASOGLU M, DURUKAN AB, GURBUZ HA. Is a "narrow aorto-mitral angle and associated factors" associated with development of systolic anterior motion? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 145:617

- VARGHESE R, ANYANWU AC, ITAGAKI S, et al. Management of systolic anterior motion after mitral valve repair: an algorithm. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012; 143:S2-7

- VESEY JM, OTTO CM. Complications of prosthetic heart valves. Curr Cardiol Rep 2004; 6:106-11

- WASOWICZ M, MEINERI M, DJAIANI G, et al. Early complications and immediate postoperative outcomes of paravalvular leaks after valve replacement surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2011; 25:610-4

- YEO TC, FREEMAN WK, SCHAFF HV, et al. Mechanisms of hemolysis after mitral valve repair: Assessment by serial echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 32:717-23.

- ZOGHBI WA, CHAMBERS JB, DUMESNIL JG, et al. Recommendations for evaluation of prosthetic valves with echocardiography and Doppler ultrasound. J Am Soc Echocradiogr 2009; 22:975-1014