The large stroke volume, bouncing pulse, very high differential pressure and retrograde diastolic flow in the descending thoracic aorta give rise to the classic physical signs: rounded, hyperdynamic apex, Musset's sign (head nodding with each systole), Corrigan's pulse (pulsus altus and celer) [4]. The arterial curve is very broad with a vertical upward slope, low diastolic pressure and a pulse pressure (PAsyst-PAdiast) of 80-100 mmHg.

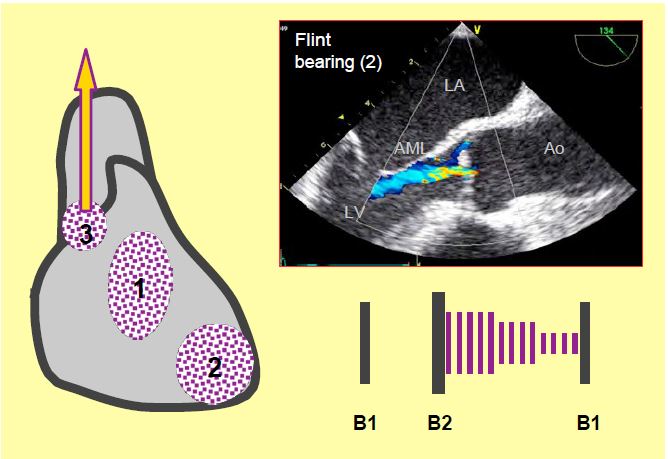

Auscultation reveals a high diastolic decrescendo murmur radiating towards the apex, with a maximum in the third and fourth left intercostal spaces in the parasternal position (Figure 11.130). It is often associated with a mesodiastolic roll (Austin-Flint murmur) caused by vibration of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve against which the jet of the AI is reflected [1]. The severity of the defect correlates better with the duration of the murmur than with its intensity [4].

Video: diastolic vibrations of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve caused by the jet of aortic insufficiency reflected on its inferior surface (4-cavity 0° view), causing the Flint roll.

Figure 11.130: Murmurs of aortic insufficiency: a soft, chirping diastolic murmur (1); accompanied by Flint's roll at the mitral focus (2), due to diastolic vibration of the anterior mitral leaflet (AML) under the effect of the regurgitant jet running along its ventricular surface; there is also an aortic ejection murmur when the systolic flow is very high (3).

The ECG shows signs of left-sided dilatation: left deviation, predominant Q and sharp T in the left territories; T-wave inversion and non-specific ST-segment depression are often seen. The chest x-ray shows very marked cardiomegaly.

While the rate is only 6%/year when LV function is preserved, the rate of symptom onset is 25%/year when the LV is failing and dilated, with a mortality rate of 20%/year [5]. Again, an enlarged LV telesystolic diameter (> 2.5 cm/m2) is the best independent predictor of survival [2].

Acute failure presents abruptly with severe dyspnoea, cardiovascular collapse and prepulmonary oedema; the patient is tachycardic and hypoperfused. The diastolic murmur is less pronounced and of shorter duration because the intraventricular pressure is high and the aorto-ventricular gradient falls rapidly in diastole.

| Clinical signs of aortic insufficiency |

| Symptoms associated with LV dilatation and dysfunction: dyspnoea (pulmonary congestion), angina (late onset). Typical signs: rapid, racing pulse, diastolic murmur. Acute AI: cardiogenic shock.

Features of aortic insufficiency Volume overload resulting in dilatative LVH |

References

- BONOW RO, BRAUNWALD E. Valvular heart disease. In: ZIPES DP, et al, eds. Braunwald's heart disease. A textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 7th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, 1553-632

- BONOW RO, LAKATOS E, MARON BJ, et al. Serial long-term assessment of the natural history of asymptomatic patients with chronic aortic regurgitation and normal left ventricular systolic function. Circulation 1991; 84:1625-31

- BONOW RO, ROSING DR, McINTOSH CL, et al. The natural history of asymptomatic patients with aortic regurgitation and normal left ventricular function. Circulation 1983; 68:509-14

- BRAUNWALD E. Valvular heart disease. In: BRAUNWALD E. ed. Heart disease. Philadelphia, WB Saunders Co, 1997, 1007-76

- NISHIMURA RA, OTTO CM, BONOW RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation 2014; 129:e521-e643