- Dilatation of the aortic root and annulus; the cusps are normal;

- Damage to the valve itself; the pathology lays at cusps level.

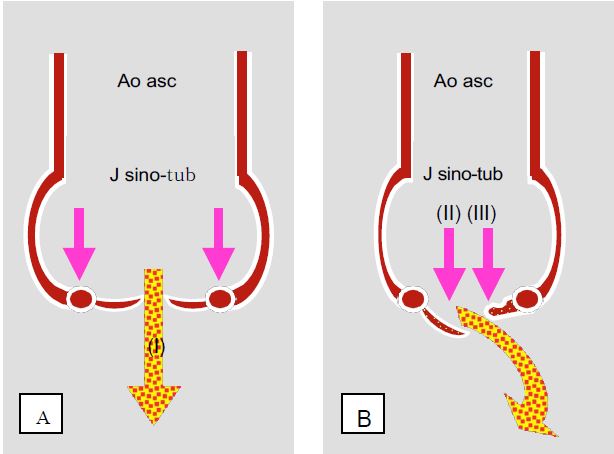

Figure 11.126: The different anatomopathological types of aortic insufficiency. A: annulo-ectasitic disease; the root of the ascending aorta and the valve ring are dilated but the cusps are normal (type I AI); the jet of the AI is central. B: The root of the aorta is normal but the cusps are damaged; they may be prolapsed (AI type II) or retracted (AI type III). The jet of the AI is usually eccentric; it is directed away from the prolapsing cusp or towards the retracted cusp.

The first is an annuloectasitic disease of the ascending aorta, which is becoming increasingly common in the West and currently accounts for half of all cases of aortic insufficiency [3]: dilatation of the annulus and the sino-tubular junction stretches the free edges of the cusps, which are normal, and prevents them from coapting properly. This condition is associated with cystic medianecrosis of the aorta, isolated or associated with Marfan's syndrome, age-related dilatative degeneration of the aorta (aneurysm) or systemic inflammatory syndromes (ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter's or Behçet's syndrome, syphilitic aortitis, etc.). Finally, the intimal flap of a type A aortic dissection may destabilise the valve apparatus or prolapse through the valve in diastole.

Video: dilatation of the aortic root leading to diastolic non-coaptation of the cusps in Marfan syndrome (simultaneous short-axis and long-axis views).

Video: Long-axis view of the aortic root in an A dissection; the membrane ("flap") protrudes through the aortic valve in diastole, causing major insufficiency.

In the second case, the insufficiency is due to lesions of the cusps, which may have different aetiologies.

- Degenerative lesions: myxoid or fibroelastic degeneration (prolapse), calcifications (rigid calcific calcifications with infiltrated valves that no longer seal in diastole).

Video: long-axis view of moderate aortic insufficiency using colour Doppler flow.

Video: Prolapse of the right coronary cusp causing major eccentric aortic insufficiency.

Video: 130° long-axis colour Doppler image in a case of aortic disease with minor insufficiency and tight stenosis; in the ascending aorta, the flow is narrow and swirling.

- Bicuspid regurgitation: although this malformation most often results in stenosis, it sometimes manifests as isolated or predominant insufficiency; its prevalence is 1-2% in the general population.

Video: short-axis view of an aortic bicuspid; the left and right coronal cusps are fused, but there are 3 commissures visible in their normal anatomical positions.

Video: Three-dimensional short-axis view of aortic bicuspidism.

- ARF: Commissural fusion and scar-like retraction of the cusps infiltrated with fibrous tissue prevents them from coapting in diastole.

- Endocarditis: destruction of the leaflets, their perforation or prolapse of vegetations through the valve causes transvalvular leak; an abscess may form in the infectious pannus surrounding the root of the cusps, most commonly at the mitral valve angle.

Video: Pendulous vegetation on the non-coronary cusp in aortic endocarditis (long-axis view)

Video: Sessile vegetations in aortic endocarditis; vegetations appear as soft tissue, less echogenic than anatomical structures.

- Loss of commissural support: trauma, A dissection, supracristale IVSD.

- Systemic disease: Marfan, syphilis, Ehlers-Danlos, rheumatoid arthritis.

- Drug toxicity: methysergide, ergotamine, pergolide, fenfluramine, phentermine, aminorex, benfluorex (Mediator® ); the toxicity of anorexic drugs has been known since the early 1990s.

Aortic insufficiency may develop slowly and remain asymptomatic for a long time, or it may occur suddenly (acute aortic insufficiency), usually following dissection, endocarditis or trauma.

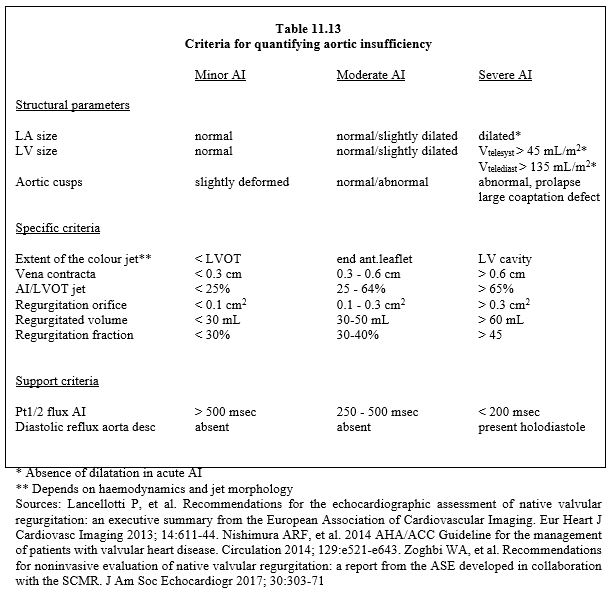

The criteria for severe AI are (see Table 11.13) [1,5,6,9,10]:

- Regurgitant volume ≥ 60 ml (regurgitant fraction ≥ 45%);

- Diastolic BP < 50 mmHg, very wide differential BP (> 80 mmHg);

- Dilatative hypertrophy of the LV;

- Large LV cavity (end-diastolic diameter > 4 cm/m2, telesystolic volume > 45 mL/m2, end-diastolic volume > 135 mL/m2); this criterion is absent in acute AI;

- Regurgitant jet extending to the midventricle (depending on haemodynamics);

- Ratio of AI jet diameter to LVOT diameter > 0.6;

- Regurgitant orifice surface area > 0.3 cm2.

In analogy to Carpentier's classification for MI, 3 types of AI are currently described according to the mobility of the aortic cusps (El Khoury classification) (Figure 11.127) [2,4].

- Type I: normal cusps, dilatation of the aortic root; central AI jet.

- Type II: Excess tissue and movement of one or more cusps, prolapse; eccentric jet.

- Type III: restrictive movement of the cusps, calcifications; variable jet.

Type I is further subdivided into 4 categories according to the degree of aortic dilatation and the mechanism of leakage [2,4,8].

- Type Ia: Dilatation of the supracoronary aorta (sino-tubular junction and ascending aorta).

- Type Ib: Dilatation of the aortic root (sinus of Valsalva).

- Type Ic: Dilatation of the aortic annulus.

- Type Id: Perforation of a leaflet.

Figure 11.127: The different anatomopathological types of aortic insufficiency according to El Khoury [2,4,8].

| Aortic insufficiency |

| Aortic insufficiency (AI) is caused by two different mechanisms:

- Dilatation of the aortic ring and root, normal cusps, central jet

- Cusp lesions, eccentric jet

Etiologies:

- Annulo-ectasitic disease, aneurysm, Marfan, flap of dissection

- Bicuspidosis, degeneration, ARF, endocarditis, trauma, drug toxicity

Criteria for defining severe AI :

- Regurgitant volume ≥ 60 mL, regurgitant fraction > 45%.

- Regurgitant orifice area > 0.3 cm2

- Dilatative LVH (LV Dtd > 4 cm/m2 ); normal LV size in acute AI

- BP diastolic < 50 mmHg, BP diastolic > 80 mmHg

AI classification:

- Type I: normal cusps, dilatation of the aortic root

- Type II: excess tissue and movement of one or more cusps, prolapse

- Type III: restrictive cusp movement, calcification

|

References

- BAUMGARTNER H, FALK V, BAX JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017; 38:2739-86

- BOODHWANI MJ, DE KERCHOVE L, GLINEUR D, et al. Repair-oriented classification of aortic insufficiency: impact on surgical techniques and clinical outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009; 137:286-94

- DARE AJ, VEINOT JP, EDWARDS WD, et al. New observations on the etiology of aortic valve disease. Hum Pathol 1993; 24:1330

- EL KHOURY G, GLINEUR D, RUBAY J, et al. Functional classification of aortic root/valve abnormalities and their correlation with etiologies and surgical procedures. Cur Opin Cardiol 2005; 20:115-21

- LANCELLOTTI P, TRIBOUILLOY C, HAGENDORFF A, et al. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurugitation: an executive summary from the EACI. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 14:611-44

- NISHIMURA RA, OTTO CM, BONOW RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation 2014; 129:e521-e643

- NKOMO VT, GARDIN JM, SKELTON TN, et al. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet 2006; 368:1005-11

- PRODROMO J, D'ANCONNA G, AMADUCCI A, et al. Aortic valve repair fort aortic insufficiency: a review. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2012; 26:923-32

- VAHANIAN A, ALFIERI O, ANDREOTTI F, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). The Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2012; 33:2451-96

- ZOGHBI WA, ADAMS D, BONOW RO, et al. Recommendations for noninvasive evaluation of native valvular regurgitation: a report from the ASE developed in collaboration with the SCMR. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017; 30:303-71