Indications

The currently accepted indications for tricuspid valve surgery are as follows [3,5,11, 19,23,26,28,30].

- Severe symptomatic TI of organic or functional origin that does not respond to medical therapy;

- Severe primary TI, even if asymptomatic, with LV dilatation (basal diameter > 4.0 cm in 4-cavity view) and signs of progressive right-sided dysfunction (TAPSE < 15 mm, S' velocity < 9.5 cm/s, longitudinal systolic strain < -20%, Tei index > 0.45);

- Severe primary or secondary TI in patients requiring left-sided valve surgery;

- Moderate or severe TI with significant annular dilatation (diameter > 4.0 cm in 4 cavities or > 7.0 cm in the surgical field) and/or LV failure in patients requiring left heart surgery;

- Severe traumatic TI, even if asymptomatic (non-emergent).

Plasty is preferable to valve replacement except in cases where the leaflets are too deformed or too restrictive. In the absence of left-sided pathology, severe primary TI in an asymptomatic patient is an indication for surgery in cases of RV dysfunction/dilatation. It is important that anaesthetists are aware of these recommendations, as their echocardiographic knowledge places them at the centre of intra-operative discussions when deciding whether or not to intervene on the tricuspid valve during left heart surgery.

If it is secondary, tricuspid insufficiency develops in parallel with the size of the annulus [15]. Measurement of annulus diameter is preferable to assessment of TI by colour jet because it is not as dependent on haemodynamic conditions as Doppler measurements; the indication for surgery is a diameter > 40 mm or > 21 mm/m2 in 4-cavity view (3,5,19). Intraoperative TEE is a necessary guide to the mechanism, indication and outcome of valvuloplasty.

Surgical procedure

Several correction techniques are available to the surgeon (Figure 11.61 and Figure 11.159) [26].

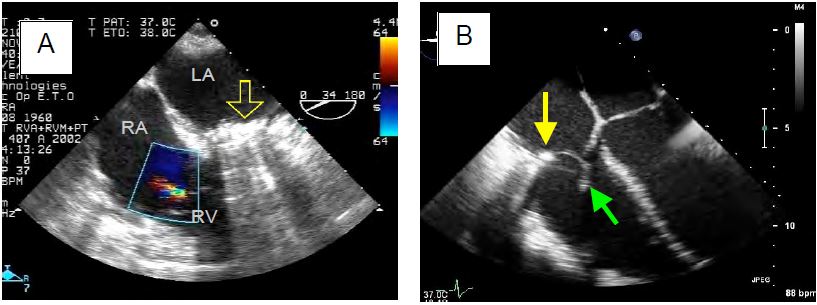

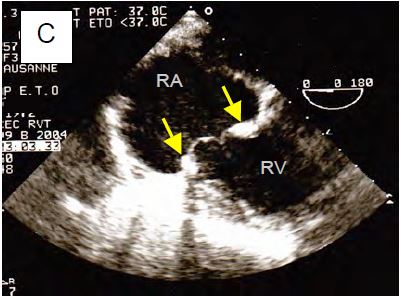

Figure 11.159: Tricuspid valve surgery. A: Minor residual TI after De Vega plasty for ARF; the mitral valve was replaced by a mechanical prosthesis (yellow arrow). B: Carpentier ring (yellow arrow) and chordal reimplantation (green arrow) for traumatic rupture of the anterior leaflet (same case as Figs 11.117A and 117B). C: Replacement of the tricuspid valve with a bioprosthesis, clearly showing the ring (arrows) and two leaflets.

- Annuloplasty using narrowing sutures along the insertion of the anterior and posterior leaflets (DeVega plasty).

- Plication of the annulus in its posterior part, completely obliterating the posterior leaflet and converting the tricuspid valve into a bicuspid valve (Kay's bicuspidisation).

- Plasty by insertion of a semi-rigid ring (Carpentier) or a saddle-shaped ring (MC3); this ring is interrupted at the level of the septum to avoid damage to the atrioventricular node and the His bundle.

- Common suture of the tips of the 3 leaflets, transforming the valve into a three-leaf clover shape in diastole (similar to the Alfieri technique for the mitral valve).

- Reimplantation of chords in the event of rupture; resection of prolapse.

Video: Result of tricuspid plasty after traumatic rupture of the anterior leaflet chords; absence of residual leakage and restrictive effect on diastolic flow (in blue).

Video: Result of tricuspid plasty for posterior leaflet tilt in Barlow's disease; minimal residual leakage.

- Replacement of the valve with a prosthesis; a bioprosthesis is implanted rather than a mechanical prosthesis because their survival is identical. In fact, the right heart is less stressed than the left, which is why bioprostheses have a longer lifespan in the tricuspid position than in the mitral or aortic position [9,13]. On the other hand, mechanical prostheses have a much higher rate of thrombosis because the flow is slow due to the very low pressure regime.

- In patients with conduction block, an epicardial lead is implanted at the same time as the tricuspid prosthesis, as it is impossible or inadvisable to pass a pacemaker lead through the epicardium.

When performed at the same time as left heart surgery, tricuspid repair is performed during rewarming while on ECC after aortic declamping. For isolated tricuspid surgery, access is via a sternotomy or right mini-thoracotomy. The operation is performed on bypass, usually with heart beating (provided there is no PFO) [3].

Outcomes

After correction, the mean gradient across the tricuspid valve must remain < 3 mmHg [12]. The average failure rate for surgical repair is 14% [22]. Predictors of failure are essentially those that characterise preoperative dilatation of the RV: basal end-diastolic diameter > 4.2 cm, basal end-systolic diameter > 3.7 cm, maximum width > 4.9 cm [17]. Functional results are better (85% of cases without revision at 10 years) and survival at 15 years is doubled with annuloplasty compared to plastic surgery according to De Vega [25]. However, annuloplasty is always preferable to tricuspid valve replacement (TVR), which has inferior outcomes: higher rate of postoperative right-sided failure (28% versus 9%), increased mortality (11% versus 4-7%), anticoagulation, risk of thrombosis (1%/year) [24,25,29]. The prosthesis is a rigid mechanical element that blocks the circular contraction of the base of the RV and limits its longitudinal contraction [22]. As a result, TVR is usually associated with LV failure requiring adequate inotropic support. Right ventricular dysfunction is the most important determinant of postoperative mortality, more important than pulmonary hypertension [23].

Success criteria for repair are more flexible than after mitral valve repair because residual leakage is well tolerated [4,14,16,25]:

- Small residual TI;

- ΔPmax < 4 mmHg;

- Vena contracta < 0.3 cm;

- Absence of PISA and systolic reflux in the IVC and suprahepatic veins.

After correction of a TI, the immediate aftereffects are difficult because the RV encounters PAR as full afterload and no longer benefits from the pressure valve represented by the tricuspid insufficiency. In addition, any mechanical system will block the subtle balance between circular and longitudinal contraction of the RV, the latter being primarily responsible for ejection into the PA. Right-sided failure is common and requires immediate use of beta-catecholamines (dobutamine), inodilators (milrinone, levosimendan) and pulmonary vasodilators, as well as norepinephrine to maintain coronary perfusion and interventricular septal balance (see Tables 12.6 and 12.11).

Surgical treatment of acute bacterial endocarditis in drug users involves removal of the valve. It is sometimes recommended not to immediately implant a prosthetic valve in this septic environment. The haemodynamics are then similar to those of a Fontan: filling of the RV is passive and depends solely on the CVP, which must remain high; spontaneous ventilation is ideal to ensure pulmonary flow [1]. In a second phase (6-9 months), the tricuspid valve can be replaced by a prosthesis.

Percutaneous procedures

Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with tricuspid surgery on ECC in high-risk patients, a number of percutaneous transcatheter techniques have been developed in recent years [2,3,21].

- MitraClip™: The device used for the mitral valve is transposable to the tricuspid valve, with a success rate of 80% [6].

- Tric Valve™: implantation of a valve bioprosthesis (TAVI type) at the neck of the vena cava as it enters the RA; this technique prevents vena cava reflux but does not overload and dilate the RV and RA.

- FORMA™: foam-filled (polymer) balloon mounted on a rod anchored to the apex of the RV and placed in the centre of the tricuspid valve; it fills the regurgitant orifice in systole, the leaflets come to rest on it and the valve is sealed.

- Triclip™: The use of a MitraClip allows bicuspidisation of the tricuspid valve at the anteroseptal and/or posteroseptal commissures and reduction of leakage.

- Trialign™: the ring is narrowed by traction between two anchor points (pledgets) at the anteroposterior and septoposterior commissures, achieving plication of the posterior leaflet.

- TriCinch™: traction by a Dacron band between the anteroposterior region of the ring and a stent implanted in the inferior vena cava; the ring is then bent as required.

- Millipede IRIS™: A fully adjustable nitinol ring is placed inside the tricuspid annulus, to which it is attached by micro-screws and then constricted to the desired size.

Two different valve implantation systems have been developed to date.

- TricValve™ (mentioned above): self-expanding nitinol bioprosthesis with pericardial valves placed in the IVC between the RA and the junction of the suprahepatic veins; the aim is to prevent systolic reflux into the IVC and associated congestion in the viscera and lower limbs.

- NaviGate™: orthotopic nitinol bioprosthesis with pericardial valves, equipped with ribs for anchoring to the tricuspid annulus; it is available in several sizes (from 36 to 52 mm).

These techniques are still in their infancy, but the success rate is already >75%; in-hospital mortality is 3.5-5.1% [27,29]. The reduction in TI is less than with conventional surgery, but the improvement in clinical status is certain. Patients are put on lifelong aspirin and anti-vitamin K for 3 months, but many are anticoagulated for atrial fibrillation anyway.

Several of these devices are implanted via the jugular vein, which must remain accessible to the operator. Intra-operative TEE is essential and justifies general anaesthesia. The anaesthetist/echocardiographer has an important role to play in the placement of these devices. Whether the approach is via the IVC or the SVC, access to the tricuspid valve requires a difficult manoeuvre in the RA because the axis of the tricuspid valve is not in line with the vena cava.

| Operative indications for tricuspid regurgitation |

| Indications depend on the degree of dilatation of the tricuspid valve, its origin and the surgical context.

- Severe symptomatic TI Repair is straightforward, but replacement is associated with very difficult post-operative sequelae. Operative mortality: 1-2% for concomitant plasty, 4-7% for isolated plasty, 11% for replacement. |

© CHASSOT PG, BETTEX D, August 2011, last update November 2019

References

- ARBULU A, HOLMES RJ, ASFAW I. Tricuspid valvulectomy without replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991; 102:917-24

- ASMARATS L, PURI R, LATIB A, et al. Transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71:2935-56

- ASMARATS L, TARAMASSO M, RODES-CABAU J. Tricuspid valve disease: diagnosis, prognosis and management of a rapidly evolving field. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019; 16:538-54

- BAJZER CT, STEWART WJ, COSGROVE DM, et al. Tricuspid valve surgery and intraoperative echocardiography: Factors affecting survival , clinical outcome, and echocardiographic success, J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 32:1023:9

- BAUMGARTNER H, FALK V, BAX JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017; 38:2739-86

- BESLER C, et al. Predictors of procedural and clinical outcomes in patients with symptomatic tricuspid regurgitation undergoing transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018; 11:1119-28

- BRUCE CJ, CONNOLLY HM. Right-sided valve disease deserves a little more respect. Circulation 2009; 119:2726-34

- CHIKWE J, ITAGAKI S, ANYANWU A, et al. Impact of concommittant tricuspid annuloplasty on tricuspid regurgitation, right ventricular function, and pulmonary artery hypertension after repair of mitral valve prolapse. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65:1931-8

- DEL CAMPO C, SHERMAN JR. Tricuspid valve replacement: Results conmparing mechanical and biological prostheses. Ann Thorac Surg 2000; 69:1295-303

- DESAI RR, VARGAS-ABELLO MM, KLEIN AM, et al. Tricuspid regurgitation and right ventricular function after mitral valve surgery with or without concommittant tricuspid valve procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 146:1126-32.e10

- DREYFUS GD, CORBI PJ, CHAN KM, et al. Secondary tricuspid regurgitation or dilatation: which should be the criteria for surgical repair ? Ann THorac Surg 2005; 79:127-32

- HAHN RT. State-of-the-art review of echocardiographic imaging in the evaluation and treatment of functional tricuspid regurgitation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 9:e005332

- KUNADIAN B, VIJAYALAKSHMI K, BALASUBRAMANIAN S, et al. Should the tricuspid valve be replaced with a mechanical or biological valve ? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2007; 6:551-7

- KUWAKI K, MORISHITA K, TSUKAMOTO M, et al. Tricuspid valve surgery for functional tricuspid valve regurgitation associated with left-sided valvular disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001; 20:577-8

- LANCELLOTTI P, MOURA L, AGRICOLA E, et al. European Association of Echocardiography recommendations for the assessment of valvular regurgitation. Part 2: mitral and tricuspid regurgitation (native valve disease). Eur J Echocardiogr 2010; 11:307-32

- LANCELLOTTI P, TRIBOUILLOY C, HAGENDORFF A, et al. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurugitation: an executive summary from the EACI. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 14:611-44

- MASLOW A, ABISSE S, PARIKH L, et al. Echocardiographic predictors of tricuspid ring annuloplasty repair failure for functional tricuspid regurgitation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2019; 33:2624-33

- NATH J, FOSTER E, HEIDENREICH PA. Impact of tricuspid regurgitation on long-term survival. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43:405-9

- NISHIMURA RA, OTTO CM, BONOW RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation 2014; 129:e521-e643

- RAMAKRISHNA H, AUGOUSTIDES JGT, GUTSCHE JT, et al. Incidental tricuspid regurgitation in adult cardiac surgery: focus on current evidence and management options for the perioperative echocardiographer. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2014; 28:1414-20

- RODÉZ-CABAU J, HAHN RT, LATIB A, et al. Transcatheter therapies for treating tricuspid regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 67:1829-45

- ROGERS JH, BOLLING SF. The tricuspid valve. Current perspective and evolving management of tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation 2009; 119:2718-25

- SHIRAN A, SAGIE A. Tricuspid regurgitation in mitral valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53:401-8

- SINGH SK, TANG GH, MAGANTI MD, et al. Midterm outcomes of tricuspid valve repair versus replacement for organic tricuspid disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 82:1735-41

- TANG GH, DAVID TE, SINGH SK, et al Tricuspid valve repair with an annuloplasty ring results in improved long-term outcomes. Circulation 2006; 114(suppl I):577-81

- TARAMASSO M, VANERMEN H, MAISANO F,et al. The growing clinical importance of secondary tricuspid regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 59:703-10

- TARAMASSO M, et al. Outcomes after current transcatheter tricuspid valve intervention: mid-term results frome the International TriValve Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018; 12:155-65

- VAHANIAN A, ALFIERI O, ANDREOTTI F, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). The Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2012; 33:2451-96

- ZACK CJ, FENDER EA, CHANDRARASHEKAR P, et al. National trends and outcomes in isolated tricuspid valve surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70:2953-60

- ZOGHBI WA, ADAMS D, BONOW RO, et al. Recommendations for noninvasive evaluation of native valvular regurgitation: a report from the ASE developed in collaboration with the SCMR. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017; 30:303-71