The prevalence of mild pulmonary insufficiency (PI) is 30-75% in the general population [2,8]. Significant PI is usually associated with pulmonary hypertension with dilatation of PA and RVOT. Severe PI is rare; it is associated with a structural valve abnormality of congenital origin (monocuspid, bicuspid, Marfan), acquired (carcinoid, endocarditis) or iatrogenic (secondary to valvulotomy and patch for correction of tetralogy of Fallot or congenital stenosis). Even severe PI remains asymptomatic for a long time, but leads to dilatation of the RV due to volume overload, right-sided dysfunction and ultimately congestive heart failure. The risk of ventricular arrhythmias is directly related to the degree of RV dilatation. The volume of regurgitation is proportional to the area of the gaping orifice in diastole, but is also influenced by pulmonary pressure, RV compliance and the duration of failure during diastole [7].

The TEE image is characteristic, although the severity criteria for the pulmonary valve are less well validated than those for other valves (Table 11.15) [3,8].

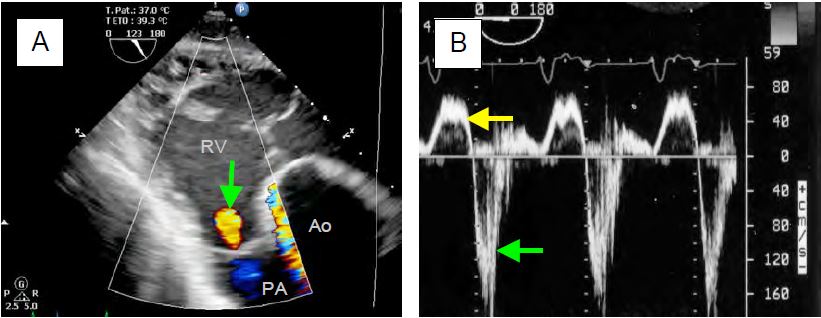

- Mild PI: small, fine, short, coloured jet (protodiastolic) emanating from a commissure or the central coaptation of the valve, directed in the axis of the RVOT during telediastole, highly variable with respiration; extent of jet < 1.0 cm (Figure 11.162A).

- Moderate PI: vena contracta diameter 2-5 mm; jet extension > 2.0 cm (dependent on PAP and PtdRV); holodiastolic flow of Vmax > 1.5 m/s.

- Severe PI: vena contracta diameter > 0.5 cm (most robust index); dilation of RV, RVOT and PA. The rapid pressure equalisation between PA and RV means that the jet does not last throughout diastole. Vmax is often low (colour flow without turbulence) because the orifice is large. These two phenomena tend to underestimate the importance of PI.

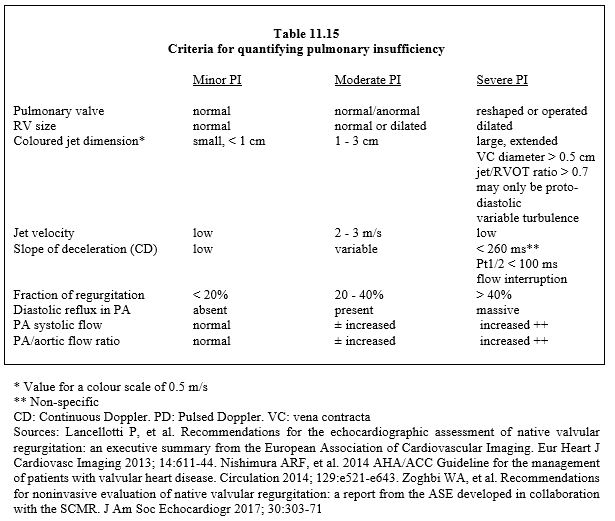

- On continuous Doppler, the image of the velocity spectrum is dense and deceleration is rapid; in severe PI, the duration of regurgitation is ≤ 60% of diastole and Pt1/2 < 100 ms [4]. Diastolic regurgitation in the PA and its branches is massive (pulsed Doppler) (Figure 11.162B).

Video: Color flow in the trunk of the pulmlary artery in severe pulmonary insufficiency; in systole, the flow is anterograde and laminar; in diastole, it refluxes towards the RV and becomes swirling.

Figure 11.162: Regurgitant flow in pulmonary insufficiency (PI). A: Mild PI in the RVOT on transgastric TEE (green arrow). B: Flow in the PA in severe PI; diastolic reflux is massive (flow below baseline, green arrow) compared to anterograde flow (flow above baseline, yellow arrow). The regurgitation extends over about half of diastole because it is massive and because of the rapid pressure equalisation between AP and RV. Pt1/2 (red line) lasts 100 ms.

In severe PI, the RV is dilated by volume overload (Vtd > 150 mL/m2, Vts > 70 mL/m2) and ventricular arrhythmias are common. Even with 3D technology, echocardiography tends to underestimate RV volume; MRI is the only technique that allows accurate measurement of right-sided volume. Measurements other than EF are useful in assessing RV function: systolic tricuspid annular excursion, systolic displacement velocity (S' in tissue Doppler), longitudinal strain and strain rate, isovolumetric contraction velocity [7]. The symptomatology is that of right-sided failure; the ECG shows a widened QRS. An increase in PAR or right afterload (IPPV) increases the regurgitant fraction and reduces anterograde pulmonary flow. Indications for surgery in severe PI are based on the impact of the pathology on the RV.

- Severe PI and dilatation of the RV with worsening of the TI;

- Severe symptomatic PI (right-sided failure, arrhythmias);

- Severe PI at the same time as another cardiac procedure.

Waiting until patients become symptomatic carries the risk of irreversible deterioration in right-sided function, so the indication for surgery is preferably based on echocardiographic monitoring [7]. Surgery consists of replacing the valve, usually with a biological valve conduit (homograft or heterograft) [6].

Video: Contegra heterograft pulmonary valve replacement in short-axis view of the aortic arch centered on the long-axis of the pulmonary artery.

Survival without reintervention after homograft is 94% at 5 years and 89% at 15 years [1]. Percutaneous technology has also been introduced in the treatment of pulmonary insufficiency with two TAVI-derived models (Melody™ and Sapien™ valves); with a success rate of > 95%, results are comparable to the bypass technique [5].

| Hemodynamics sought in cases of pulmonary insufficiency |

|

Right preload adapted to RV function Inotropic support - Systemic closed - Pulmonary open |

© CHASSOT PG, BETTEX D, August 2011, last update November 2019

References

- BOKMA JP, WINTER MM, OOSTEHOF T, et al. Individualized prediction of pulmonary homograft durability in tetralogy of Fallot. Heart 2015; 101:1717-23

- KLEIN AL, BURSTOW DJ, TAJIK AJ, et al. Age-related prevalence of valvular regurgitation in normal subjects. A comprehensive color flow examination of 118 volunteers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1990; 3:54-63

- LANCELLOTTI P, TRIBOUILLOY C, HAGENDORFF A, et al. Recommendations for the echocardiographic assessment of native valvular regurugitation: an executive summary from the EACI. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 14:611-44

- LI W, DAVLOUROS PA, KILNER PJ, et al. Doppler-echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary regurgitation in adults with repaired tertralogy of Fallot: comparison with cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Am Heart J 2004; 147:165-72

- MALEKZADEH-MILANI S, PATEL M, BOUDEJEMLINE S. Folded Melody valve technique for complex right ventricular outflow tract. Euro Intervention 2014; 9:1237-40

- NISHIMURA RA, OTTO CM, BONOW RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation 2014; 129:e521-e643

- SCHILLCUTT SK, TAVAZZI G, SHAPIRO BP, DIAZ-GOMEZ J. Pulmonic regurgitation in the adult cardiac surgery patient. J Cardiothorac Vacs Anesth 2017; 31:213-28

- ZOGHBI WA, ADAMS D, BONOW RO, et al. Recommendations for noninvasive evaluation of native valvular regurgitation: a report from the ASE developed in collaboration with the SCMR. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017; 30:303-71